Eight pages bound in furry seal skin may be Norway's oldest book

The little book is so rare that the National Library of Norway is bringing in experts from around the world to learn more.

When conservator Chiara Palandri first saw the book, she realised that it was something truly special.

The book had been privately owned at Hagenes farm in Bergen until now. The story passed down through generations says it came from a monastery in Western Norway.

Earlier this year, the family handed the book over to the National Library of Norway.

Every old manuscript and book that arrives there undergoes a thorough examination.

"We conduct a condition assessment. We look for damage or mould and how stable the manuscript is," says Arthur Tennøe. He heads the Visual Media and Conservation Department at the National Library.

The little book was worn and deteriorated. But Palandri quickly saw that it was unique.

"I had never seen such a binding before," she tells Science Norway.

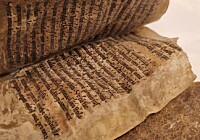

The 13th century or older

The book is stiff and fragile, so it must be handled with great care. Only conservators are allowed to touch it.

The book containing religious songs, now known as the Hagenes manuscript, is from the 13th century.

"This is a preliminary estimate. It may be even older," says Palandri.

Around 1200, Christianity was well established in Norway.

"There was vibrant Christian life. There were parish churches, cathedrals in the big cities, and monasteries. They were closely connected to scholarly and religious networks in other European countries," says Åslaug Ommundsen. She is a professor of medieval Latin at the University of Bergen.

Most of it disappeared

Documents and books from the Middle Ages are rare.

From 1537, Norway became Protestant. The old, handwritten Catholic books became outdated and uninteresting.

Printed books eventually arrived. Old parchments were reused to bind the new paper books.

Then time passed. Texts from the Middle Ages gained new value. But when Denmark ruled over Norway, old books and manuscripts were sent out of the country. The Danish king was the one who claimed important relics of the past.

A book meant to be used

"A lot of our oldest cultural heritage has not been preserved," says Tennøe.

That makes the little book that has now arrived at the National Library all the more valuable.

"We have so few writings from this period, and our research often relies on fragments of manuscripts. When we heard that several handwritten pages had come in, still in their original binding, it was unbelievable. This will greatly expand our knowledge base," says Ommundsen.

She especially appreciates that it appears to be a book meant for use.

"Early modern book collectors were usually interested in luxurious works with gold, beautiful illustrations, or rare texts. This book feels incredibly authentic. It's the kind of thing a priest or cantor would carry to use in church," says Ommundsen.

"A simple practical book like this would not always catch a collector's eye. That's why there aren't many of them from this period, not even in the rest of Europe," she says.

Got help from France

The text is written on animal skin. Calfskin was commonly used for parchment.

The seal-skin binding, however, is extremely unusual.

Conservator Palandri reached out to her network of colleagues in other countries. She got a response from a French researcher with a doctorate in bindings, including seal-skin bindings.

"She said our book does not resemble the ones she has studied, but that it points towards Nordic production – maybe even Norwegian," says Palandri.

Norwegian Latin

A researcher at the National Library, Espen Due-Karlsen, looked more closely at the text in the book. It is written in Latin, but the very rustic style of writing makes it highly likely that the book was written in Norway.

Ommundsen has received photos of the Hagenes manuscript. The writing suggests that the book was intended for practical use.

"It's a skilled scribe with a local touch. He's not writing to create a status symbol, but because someone needed these songs," she says.

In technical terms, the songs in the book are called sequences, written to honour a saint or mark a feast day.

They were sung in church by a cantor – lead singer – or the priest before the reading of the Gospel during mass.

"Sequences, often called festal hymns, were only sung on feast days, but there were plenty of those," she says.

Ommundsen notes that the book includes a song for Mary and one for All Saints' Day.

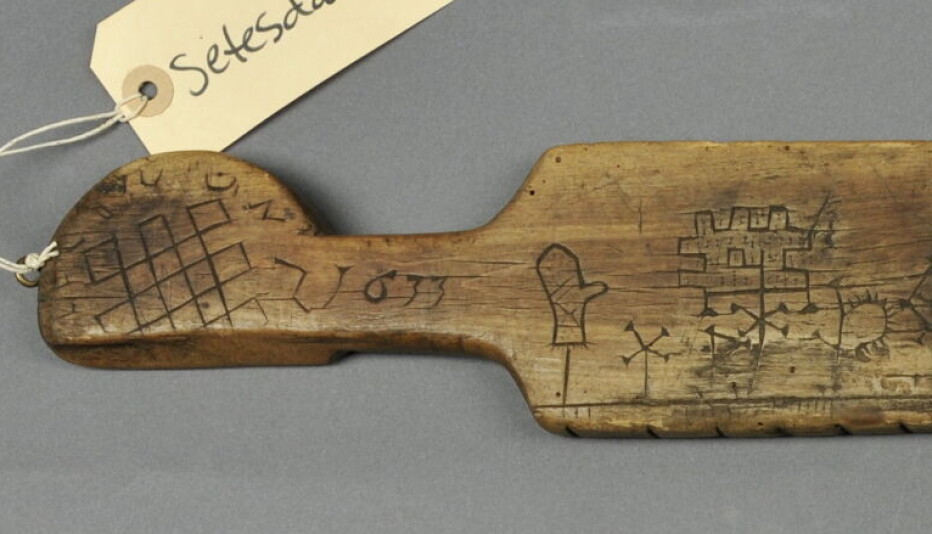

Only two others that are as old

There are only two other Norwegian books of the same age.

One is the Kvikne Psalter from the first half of the 13th century. It still has its original binding. The psalm book with wooden covers is on display at the National Library.

The other is the Old Norwegian Homily Book in Copenhagen. It lacks its original binding.

"In the seal-skin book, all the elements are original. That makes it only the second book from the Middle Ages preserved in its entirety," says Palandri.

Where did the seal swim and the calf graze?

The book has eight pages today. But there were originally more.

The spine is thicker than the contents suggest. Palandri has also found holes and remnants of parchment and stitching, indicating that several pages are missing.

She has taken samples from the pages and the cover, which have been sent for protein analysis.

This can confirm that the cover is made of seal skin and the parchment of calf. The next step is DNA analysis.

"With DNA we can determine the age of the materials, which seal species was used for the cover, and where the animal that became the parchment lived," says Palandri.

Some seals swim far, others stay in one area. If the cover is from a specific seal species and the calf turns out to have grown up in Norway, then the origin becomes clear.

Plan to make a copy

The book was held together by a strap. Only traces of it remain today.

"At first we didn’t pay much attention to the strap, but now we suspect it might be reindeer skin. We’ll do new analyses to confirm it," says Palandri. "If all the parts of the book were made at the same time, it all lines up. Then we can say with confidence that the book is Norwegian."

In November, the National Library will host a large seminar. International experts on medieval manuscripts will attend.

The seminar will focus on the seal-skin book. The following day, participants will create a replica of it.

"Mostly, it will just be fun. But by recreating it, we learn more about how it was originally put together," says Palandri.

The insects can stay

It was mostly monks who could write in the Middle Ages. The text here is very even and beautifully executed. Along the edges of each page are small dots.

"They were used to make the lines," says Palandri.

The text is written in black and red ink, with initials in red and blue-green.

The ink won't help them determine whether the book comes from Norway. The same colours were used everywhere in the Middle Ages.

Palandri also found something unexpected when she studied the book under the microscope.

"I saw two small insects," she says.

They get to stay.

"They're dead, so for now they won't be removed," she says.

Balancing protection and access

For the National Library, preserving old texts is a balancing act.

"We must protect old books and manuscripts from damage, but at the same time the material is there to be used," says Tennøe.

A specialist in photographing old books has taken extremely high-resolution photos. This allows researchers to study the text and the book without touching it.

"Digitalisation really helps. Now you don't need to physically flip through the material to study it," says Tennøe.

The conservators, however, will continue to learn from the 800-year-old object.

"We only bring out the book very rarely, and we try to handle it as little as possible," says Palandri.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.