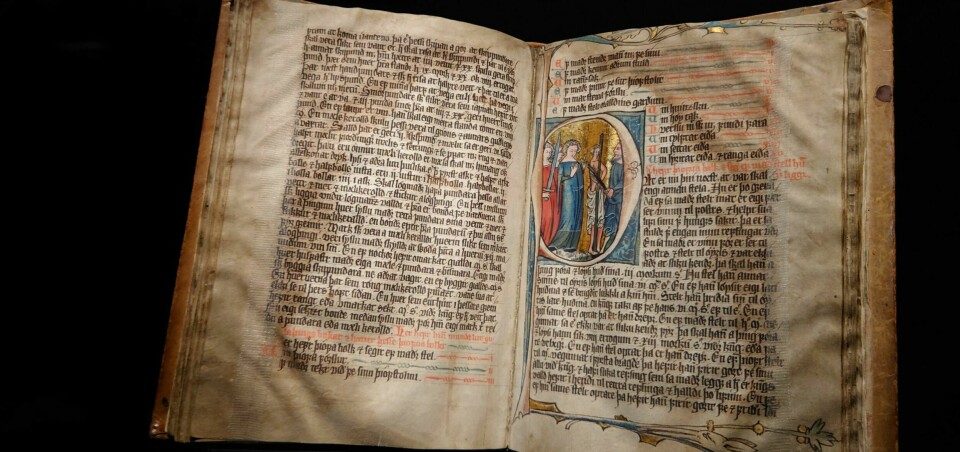

What glitters in this book is actually real gold.

Real gold leaf in the illustrations attests to the exceptional importance of this book.

This book made medieval Norway a kinder country

In a time that many believe was dark and merciless, Norway produced an unusually fair-minded piece of legislation.

Norway in the 13th century: The descendants of people who were thralls – or slaves – in the Viking Age have become a separate impoverished class without permanent residences. They travel around, causing unrest and committing crimes.

In the Viking Age, it was the family's job to take care of their kin if they fell on hard times. In 13th century Norway, you can no longer count on that happening.

King Magnus VI sees the problems caused by brutal poverty.

The king understands that something has to be done, says Professor Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde. He works at the University of Oslo's Department of Public and International Law.

The first law books

“It’s a true European masterpiece,” Sunde says about the Norwegian Code of the Realm from 1274, known in Norwegian as Magnus Lagabøtes landslov.

The idea of creating laws to govern societal development emerged a hundred years earlier, he says.

The king of Sicily tried his hand at a new legal code in 1231. Its impact was only mediocre.

“But then again, the first car wasn't that great either,” Sunde tells sciencenorway.no.

The next iteration of legal code appeared in 1265. King Alfonso X of Castile’s legal codes were on a completely different level, he says. Now they understood how to govern a society through legislation.

“It was terribly good, but was never used," he says.

Extremely successful in Norway

Rumours of these codes nevertheless spread, and people in the north become inspired. The third attempt comes from King Magnus the Law-mender in 1274, bringing one common, national law to the entire Norwegian kingdom.

“The content is good, suitable for changing society. It was put to use – and society was changed. It was avant-garde in its day,” says Sunde.

It did not become outdated for 400 years. Then it was replaced.

This relatively small law book regulates all of society. It plants the seed for conducting politics in a modern way, according to Sunde.

In an op-ed in Aftenposten, Aslak Sira Myhre, director of the National Library of Norway, writes that the Code of the Realm is just as important as the Norwegian Constitution.

However, Sunde emphasises that they cannot be compared.

“But it was an extremely successful project in its day," he says.

What makes it so significant?

Living children put in their parents' graves

The Older Gulaþing Law stated that if a child of poor means lost both parents, a grave should be dug in the cemetery. The living children were to be put in the grave, according to Professor Hans Jacob Orning on Norgeshistorie.no (link in Norwegian).

The last-surviving child in the grave was to be raised and supported by people in the village, writes Orning. The others were to be buried in the same grave.

The Older Gulaþing Law applied until 1267. The New Gulaþing Law then operated for seven years, Sunde writes in the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

“Then the Norwegian Code of the Realm comes into effect and regulates poverty in a more sophisticated way,” he says.

Obligated to feed beggars

The king decides that residents are obligated to help people survive. It becomes a duty to feed beggars because the most vulnerable individuals cannot be punished for stealing food.

The support system for the poor is responsible for ensuring that people in the village take care of their own. Those in need must make the rounds to obtain lodging and food. We’re not talking luxury, Sunde emphasises. They might sleep in the loft of a sheep shed and be fed thin gruel. But they are kept alive.

“The Code of the Realm wasn’t without controversy. It pushed boundaries and provoked resistance,” says Sunde.

It was partially sabotaged, so it had the greatest effect over time. Although it took a while, it changed society and people's way of thinking, he says.

The national law did not benefit everyone. A law never does that, according to Sunde. The law was designed to strengthen women's position in marriage. They received greater property and inheritance rights.

“The fight to strengthen women's position in marriage means that women outside of marriage had a weakened position,” he says.

Why did the king think so differently?

Religion and Christianity permeated all parts of society in the Middle Ages, says Sunde.

King Magnus VI was not a lawyer. He was not active in politics, and he did not formulate the laws or create the Code, says Sunde.

But he contributed ideas, which probably stemmed from his education with the Franciscans in Bergen. They were Catholics, and the members were completely without posessions. They were supposed to live solely off donations, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

King Magnus became concerned with caring for the poor and learned that a surplus from trade was needed to have something to give to the poor, according to Sunde.

“What makes the national law so radical was as least partly that he took Franciscan teachings seriously. He adopted structures from the legal practices of Italy’s city republic and introduced them into the Kingdom of Norway," he says.

“I don't think we can stress the Franciscan background enough."

If you delve into legal texts on common land – legislation regarding the ownership of natural resources, rivers, and water – you will discover that much remains unchanged from 750 years ago, according to Sunde.

The law decides, not the judge

Beyond specific laws, which certainly have been modernised, has the Code of the Realm from 1274 continued to influence Norway today?

“One thing that has influenced us a lot is the principle that it is the law and not the judge who decides. It is not enshrined in the Constitution, but it’s still a principle that permeates Norway’s rule of law,” Sunde says.

The state law was early in fighting judicial corruption. Sunde believes the Code of the Realm has contributed significantly to Norwegians' trust and confidence in the judicial system.

For example, Norway has three times as many lay judges than Denmark, he says. And the UK has only one-tenth as many. A lay judge is essentially an individual who is not professionally trained in the law.

Created at exactly the right time

Sunde says that the law was created at just the right time to become significant.

“Had it been created in 1220, it wouldn’t have become as important,” he says, adding that the 13th century was an enlightening period.

The theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas rediscovered Aristotle's texts in this period. He sought to reconcile faith and reason, writes the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

“The timing – that it gathered together so many ideas and influences from the century when it was created – is what has enabled the law to endure,” says Sunde.

Monks created the illustrations

The National Library of Norway has borrowed the Hardenberg copy of the Code of 1274 from the Royal Library in Copenhagen. It was written in Bergen in the early 14th century.

“Monks, presumably from Iceland, sat and illustrated the beginnings of each chapter,” says Sunde.

This particular copy belonged to a lawspeaker in Bergen. Myhre describes it as probably the most splendid book ever made in the history of Norway. Real gold leaf is used in the illustrations.

Several hundred copies, albeit not as beautiful, likely existed around the country, giving many people access to the Code of the Realm.

The legal text was written in Old Norse, the language of Norwegians at that time.

Most important document from the Norwegian Middle Ages

“The 1274 Code of the Realm is the most important document we have from the Norwegian Middle Ages. It is perhaps also the most important artefact in the long history of how Norway has become what it is today," Myhre writes in his op-ed in Aftenposten.

“But the law hasn’t had the place it deserves in our understanding of our own history,” he writes.

“The Code was so radical that when it disappeared only 400 years later, women, children, and the poor ended up with fewer rights than they had had with the Code from the Middle Ages,” Myhre says in a video from the National Library (video in Norwegian).

The Norwegian Code of the Realm of 1274 marks something we may have forgotten, he says, and that is that Norway in the Middle Ages was a large and important European kingdom and part of a European intellectual tradition.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no