While her husband was doing forced labour for embezzlement, Maren Bang wrote the first Norwegian cookbook

The recipes used local foods and were aimed at the general public. The cookbook ran through many editions – until it was forgotten.

The most famous Norwegian cookbook authors from the old days are probably Hanna Winsnes and Henriette Schønberg Erken. Several books and articles have been published about them.

Erken's cookbook from 1914 is still sold today. Winsnes has streets named after her, and many people believe her famous cookbook from 1845 was the first in Norway.

But Maren Elisabet Bang beat Hanna Winsnes by 14 years.

Maren has essentially been forgotten.

Very little is known about her.

Financial trouble

The person who knows the most about Maren Bang is author and retired journalist Henry Notaker. He delved into archives and letters, and wrote the foreword to her first cookbook when it was reprinted in 1,000 copies in 1993.

Maren was born in 1797 in Eastern Norway into a family with financial disarray and money disputes.

Her father died when Maren was 12 years old, Notaker writes. The mother was left alone with 10 children. An eight-year gap in Maren’s life story ensues. Did she grow up in poverty or did her mother get help from the family?

Public marriage records reveal that Maren married Lieutenant Lauritz Bang at the age of 20, and that they moved to Oslo, Norway's capital.

There, Lauritz switched to a civilian office job. His income was meagre, so he took on an extra job at Norges Bank.

That's when things went wrong.

13 years of forced labour

Lauritz helped himself to cash and was caught. He was sentenced to 13 years of forced labour.

At that time, the most serious crimes were punished with forced labour. The prisoners worked at various construction sites in the city and walked around in prison garb, with heavy chains around their body, legs, and arms, according to norgeshistorie.no (link in Norwegian).

Maren sent a letter to the king and asked for the sentence to be overturned. She would rather have Lauritz exiled so the family could be spared the shame.

How will our two children fare when they have to witness their father's disgrace? she asked in her letter to King Karl Johan.

She was not successful, but Lauritz was transferred to Fredriksten Fortress in Halden.

The bank declared Lauritz bankrupt. As a result, Maren was left with no income.

Notaker believes she received help from her family. She also opened her home to guests, offering food service and takeaway.

Local food

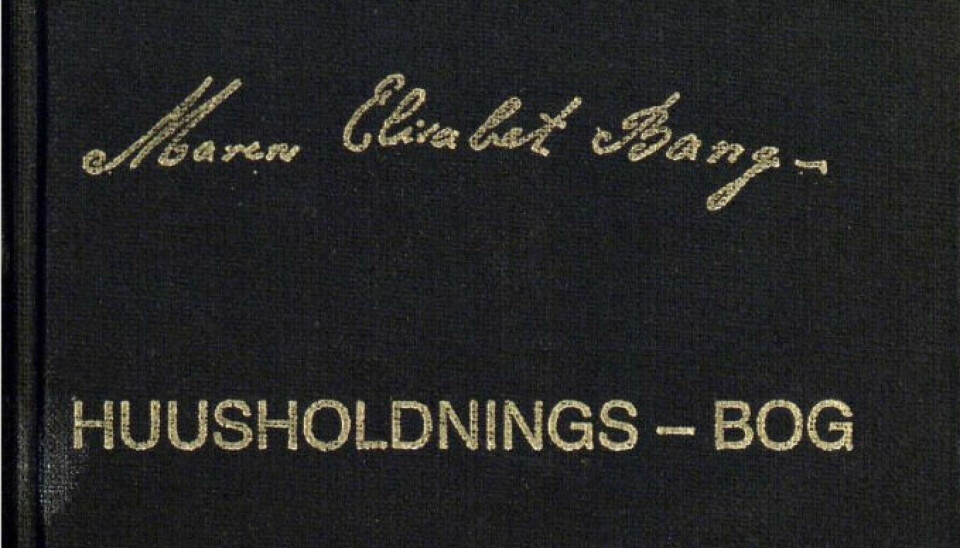

And so, Maren became an author. The Husholdnings-bog, indrettet efter Den almindelige Brug i Norske huusholdninger (Household Book, Prepared in Accordance with Normal Practice in Norwegian Households) appeared in 1831. It was the first printed cookbook in Norway.

Many of the earliest cookbook authors translated foreign recipes.

So did Maren Bang. Notaker found one of her recipes in a Danish cookbook from the 18th century.

“But Maren is special because she also includes local recipes. A lot of cheese and milk was used in Norwegian food culture, which was not the case in Denmark and elsewhere in Europe,” Notaker tells sciencenorway.no.

The cookbook includes many dishes with cheese and milk that Maren collected in Norway.

“It’s quite incredible that she ventured into recipes that didn’t already exist in international cookbooks,” Notaker says.

Maren also did something else that was unusual.

For ordinary people

“Maren's cookbook is aimed at ordinary people. That's unique,” says Notaker.

The book sold out and was reprinted.

Four years later, a smaller and more affordable version – Den norske Kokkepige (The Norwegian Cookmaid) – was published.

At first, Maren did not publish the books under her own name, but as an Association of Housewives. This was common practice abroad, according to Notaker. But eventually, the books came out under Maren's name.

Lauritz was pardoned after 12 years. But then came the next scandal.

New problems

A young woman stated that the ‘former Lieutenant Lauritz Bang, later forced labourer’ was the father of her child.

The young daughter ended up in a foster home, and Maren moved in with her husband in Halden. But the couple's finances were in poor shape.

Most viewed

New editions of Maren’s cookbooks were published, adding new recipes to reused material, as well as separate books on butchering, pickling, and cleaning.

Her tenth book, about baking, appeared in 1847. Then she stops. Maren experienced two new tragedies.

First, her son disappeared. He travelled abroad and was never heard from again.

Then Maren and Lauritz moved to Kristiansand, southern Norway, where their daughter lived. Three years later, the daughter died during childbirth.

Starting over

The couple stayed in Kristiansand, perhaps to be close to their three grandchildren.

According to a local historian, Lauritz Bang bought a house, which was right next to the seamen's school. There, he rented out rooms and ran a restaurant.

It seems like Maren was responsible for the cooking, writes Notaker.

Lauritz died in 1862 of lung disease. Maren is then 65 years old and is starting life from scratch yet again. The house and inventory were sold at auction to pay off debt.

Maren then returned to doing exactly what she had done the last time she had to support herself.

She wrote cookbooks. First, one intended for farmers, with advice and tips on caring for livestock, and recipes for cheeses and butter. Then, a wine book, with recipes for liqueurs, fruit wines, and punch.

Marketing trick

Maren’s final cookbook was published in 1864, with 780 pages and over 2,000 recipes. Maren and the publisher may have pulled a marketing trick, because even though the book is new, it says that it is the 7th edition.

Printing multiple editions was considered prestigious, writes Notaker. Also notable, is that Hanna Winsnes' cookbook had just come out in a seventh edition.

A relative of the family remembers the Sunday dinners from this period, where they ate fresh meat with horseradish sauce and clear soup. Maren is described as being of medium height, with a large nose and as a fun lady.

At around age 70, Maren moves back to the capital.

Again, we have limited information about how she lived. A grandchild says that she received money from prosperous family members. Another grandchild wrote that he remembers eating good food and delicious desserts at grandma Bang's, according to Notaker.

Maren Bang dies in 1884, 87 years old.

A heroic lady

Henry Notaker is the one who has written most about Maren Bang, but he still finds it difficult to describe what she was like as a person.

“She was certainly a heroic lady. She started creating cookbooks when she had to support herself and her two children. Later, when her husband dies, she writes new books,” says Notaker.

She also stood up for herself.

“When she discovers that a printer has published a new edition of her book and made money from it, she argues about the rights. It was not well regulated at that time," says Notaker.

But why was she forgotten?

Laid the groundwork

Hanna Wisnes received a commemorative plaque with the inscription ‘With thanks from Norwegian women,’ according to snl.no (link in Norwegian). Maren Bang has been forgotten.

“Isn't it strange? It’s wrong that Bang hasn’t received more attention,” says Annechen Bahr Bugge, a food historian at OsloMet.

In the article about Hanna Winsnes in the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian), Bugge wrote that Winsnes published the first classic cookbook in Norway, that follows the same template as cookbooks today.

“But someone had to lay the foundation. We don’t know the history of these pioneering women well enough. As researchers, we have a big and important job to do,” Bugge tells sciencenorway.no.

She is not sure why Bang has been forgotten, while Winsnes hasn’t.

Winsnes hit the trends just right

“Bang wrote anonymously at first, and she had a messy life story,” says Bugge.

Winsnes, on the other hand, enjoyed great respect in her time as the wife of a priest.

She also hit several trends well, according to Bugge.

“This was a time of rapid technological development. The wood stove and the meat grinder came to Norway and revolutionised cooking,” Bugge says.

The economy had also improved, providing better access to various goods.

“Even today, it can be difficult to explain why some cookbook authors become so much bigger than others. It might have to do with flair or hitting the trends just right,” says Bugge.

Winsnes’ special techniques included using existing dough recipes to launch modern cookies – like the ones Norwegians still make for Christmas. She emphasised appearance and presentation.

16 carrots in one cake

“Winsnes also explained how to use the new technology. And she included methods and quantities in her recipes. Bang has looser descriptions,” says Bugge.

Henry Notaker also praises Winsnes.

“Her books were well-written and educational. It’s no wonder that Winsnes gained such recognition, and that her books saw 13 editions. But Bang was the pioneer. She was the first one out,” he says.

Winsnes was probably familiar with Bang's cookbooks.

“Winsnes does not refer to Maren Bang in her books, but she certainly knew about her. I found traces of Bang's methods in Winsnes’ recipes,” says Notaker.

His goal is to try his hand at Bang's carrot cake with 16 grated carrots and 8 eggs.

References:

Bang, M.E. Huusholdnings-Bog. Indrettet efter den almindelige Brug i norske Huusholdninger (Household Book. Prepared in Accordance with Normal Practice in Norwegian Households), 1831. Reprinted in 1993 with a foreword by Henry Notaker.

Maren Elisabeth Bang. Article in the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no