Did the Norwegians in America know that the land they were given was stolen?

"They certainly had an idea of the situation for the Native Americans," says historian Anna Peterson.

(MINNESOTA): In 1867, Hans Nielsen Gamkinn in Wisconsin writes home to his family in Norway:

There isn't much government land left around here, but they are about to buy a large area from the Indians about one day's journey south of here. It will soon be opened for settlement and it is some of the best land in America. So I think it would be an advantage for a settler to make use of this opportunity.

Norwegians immigrated to the United States in droves from 1825 to 1930.

Here’s what it looks like today in rural Minnesota, one of the states where Norwegians settled.

Here, in the Midwest, immigrants were drawn by large landholdings they were given by the US government. They only had to farm the land for five years.

Starting in the mid-1800s, the government gave immigrants 160 acres of land.

Free land was attractive to the immigrants, who had been tenant farmers or came from small farms in Norway.

But the land they were given was not empty.

Cleared the country of immigrants

More than 500 Indigenous nations and tribes lived in North America before the arrival of Europeans. They had been there for thousands of years.

Europeans began to come to the US in the 1600s. They quickly started buying and taking land from the Indigenous populations.

But the expulsion of Native Americans was systematised and accelerated from 1830, when the Indian Removal Act was passed by Congress. The purpose of the law was to push Indigenous peoples westwards.

It was at this point the Norwegian immigrants came to the Midwest, hungry for land. They came to lands from which Indigenous tribes had recently been forcibly relocated. Or they became neighbours with tribes living in designated areas.

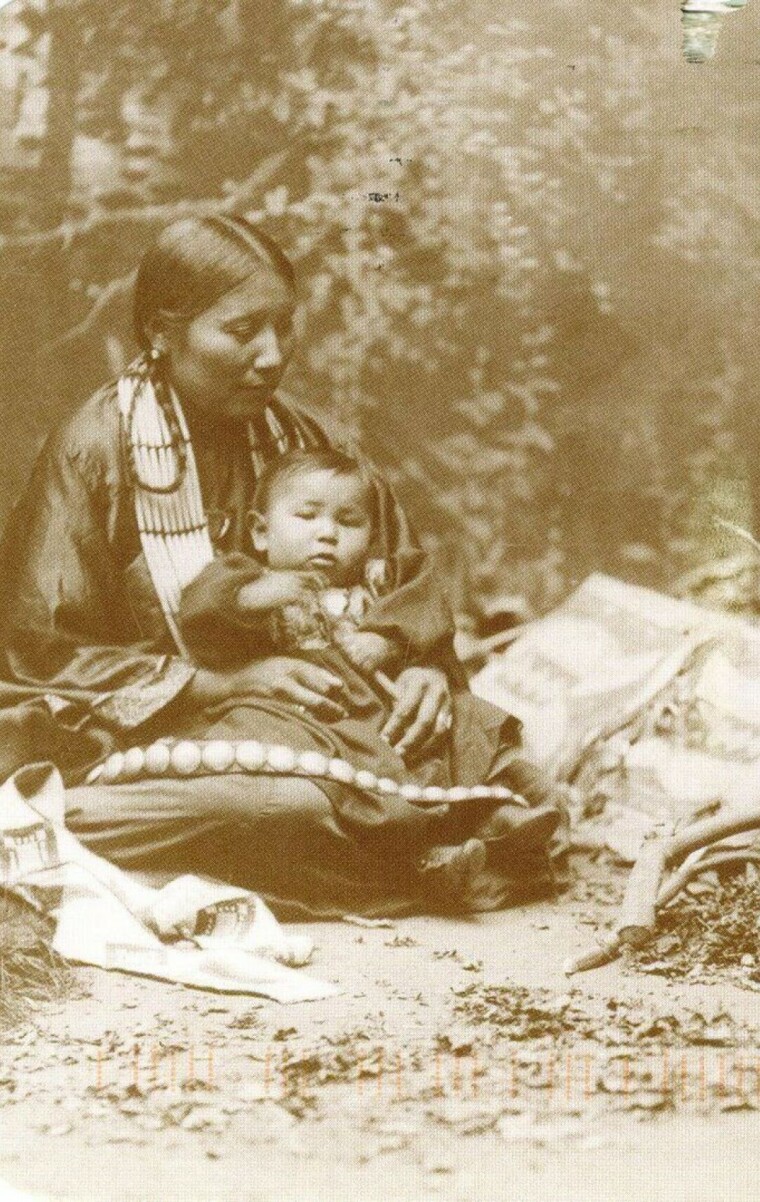

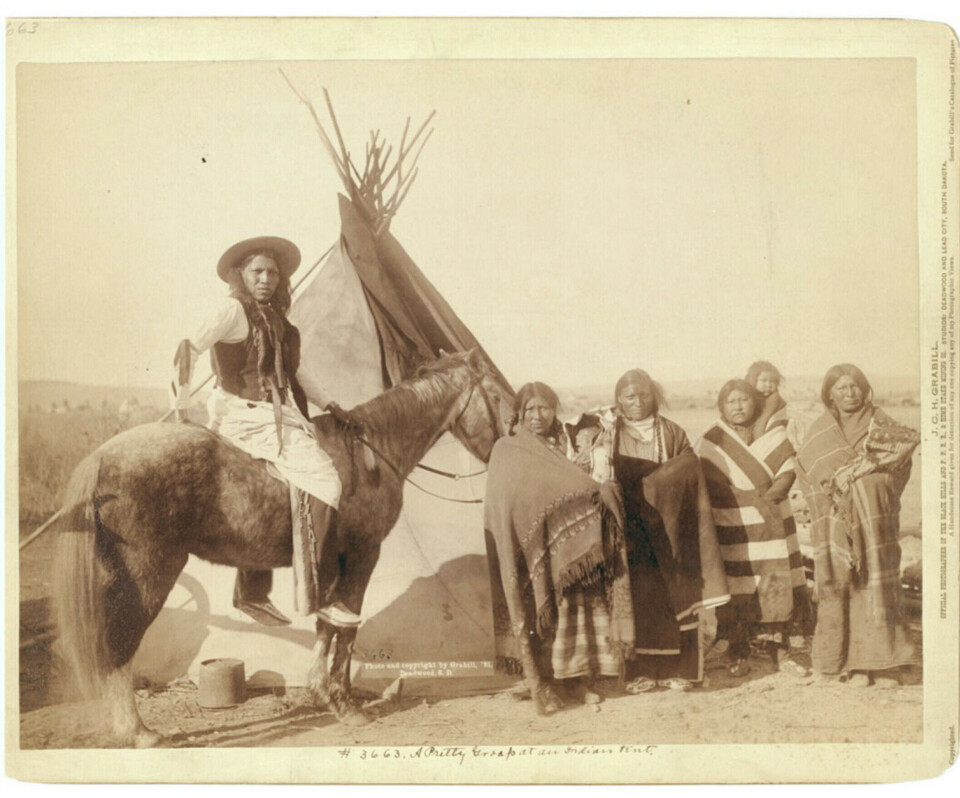

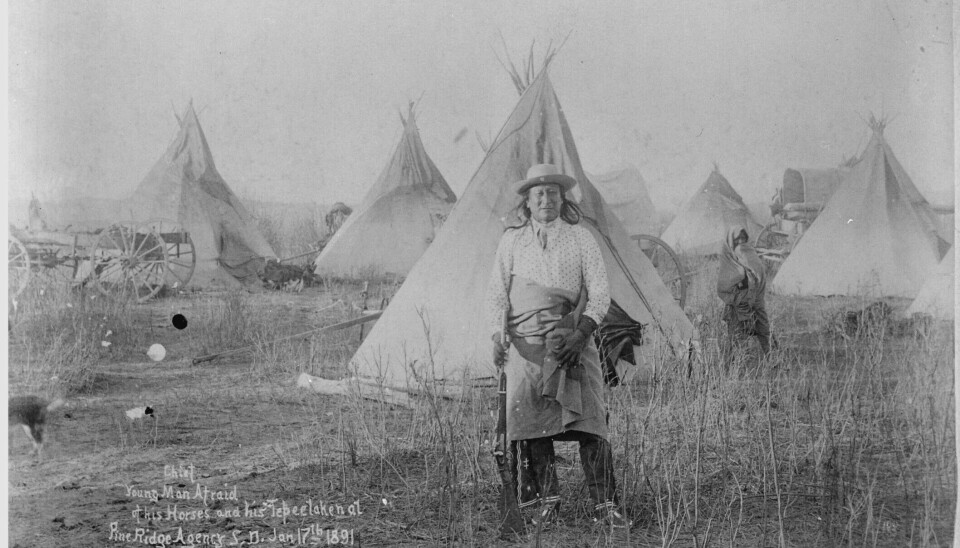

The Dakota people lived in Minnesota when Norwegian immigrants arrived.

This photo was taken in the 1800s.

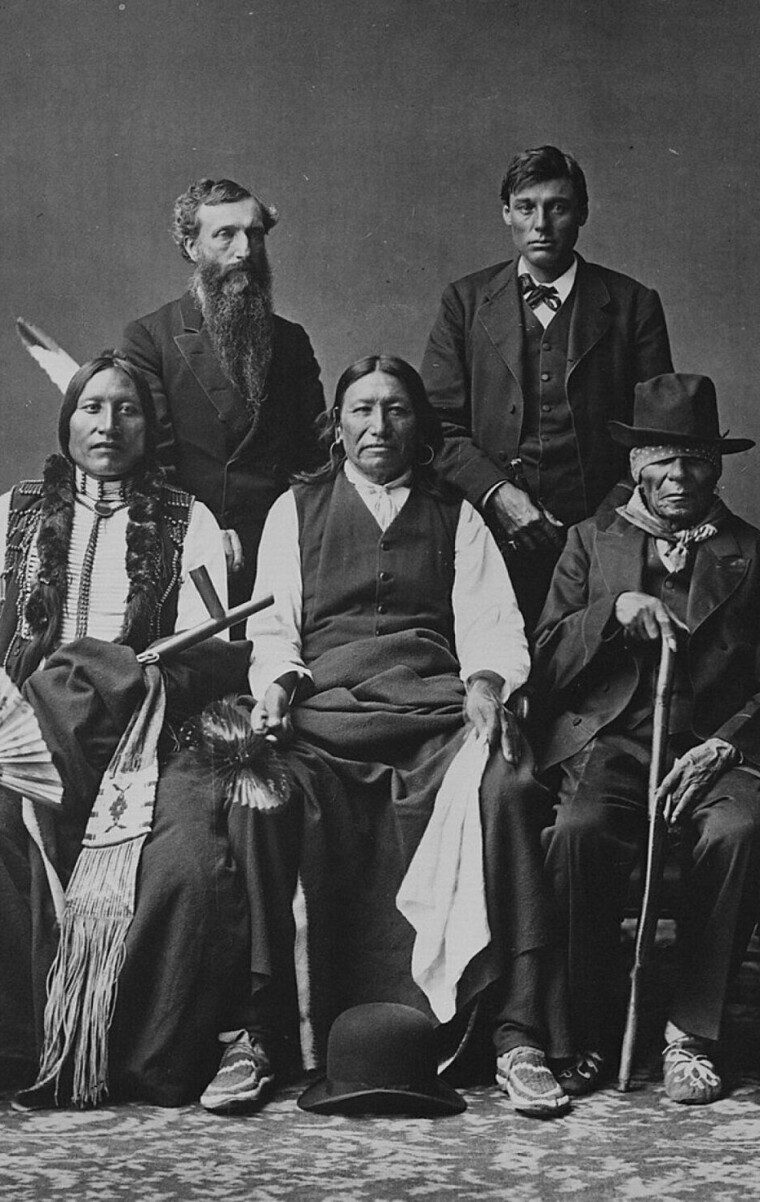

The leaders of Indigenous nations went to Washington to negotiate with the government. Here’s a delegation from the Dakota people in the 1870s. (Both photos: National Archives at College Park)

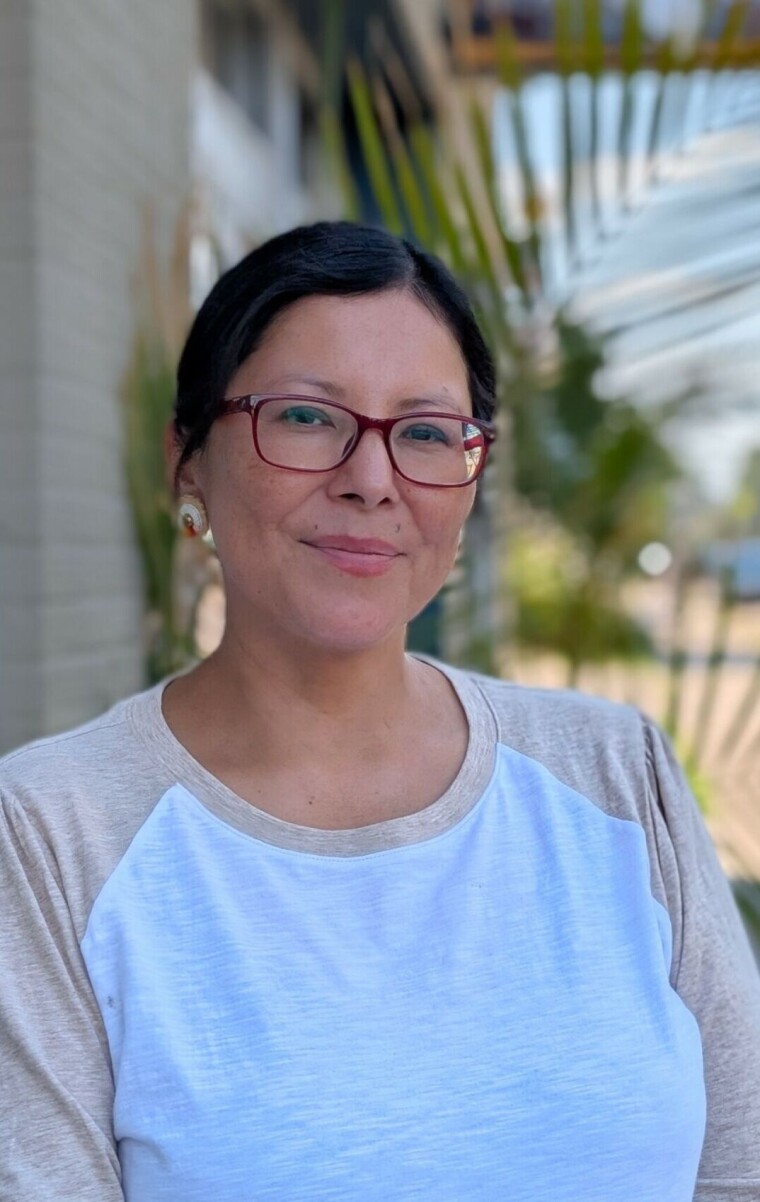

"Tribes and nations were being exterminated or removed to clear the land for white settlers," says Deidre Whiteman.

She is Spirit Lake Dakota.

"They made new laws and deployed the army, while the Indians desperately tried to figure out how to save their way of life," she says.

Whiteman is the Director of Research at the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in Minneapolis. Her ancestors lived in Minnesota.

“I can't speak for every tribe, but for my own tribe and what I understand as a historian. I am Spirit Lake Dakota. So when they were coming into our country in the 1800s, in order to survive, we had to come into agreement with the settlers,” says Whiteman.

200 years since the first emigrants left

In 2025 it will be 200 years since the first Norwegian emigrants travelled to the USA. Science Norway's reporting trip has been made possible through support from the Fritt Ord Foundation. Science Norway has full editorial freedom.

Invasion and genocide

The authorities in Washington committed to paying for the land. They promised food and supplies.

“All the treaty obligations were violated, and the government wasn't upholding their end of the bargain even though we left our ancestral homelands. It was encroachment, displacement, genocide,” says Whiteman.

The mass slaughter of bison, which was the main source of subsistence for many tribes, led to food shortages and starvation. Indigenous peoples became ill and died from imported diseases.

“My grandmother told me stories about what her grandparents experienced, so it's not that far removed,” says Whiteman.

"The Norwegians knew”

"The Norwegians certainly had an idea of the situation for the Native Americans," says Anna Peterson, a historian at Luther College in Iowa.

She studies Norwegian immigrants and their relationship to Indigenous people in the United States.

The Norwegians saw Native Americans being displaced while they themselves were on the land that belonged to those who were ousted.

“Historians mostly agree that they knew that the land had been taken from us. But these were poor people who were given so much. Greed made them turn a blind eye,” says Whiteman.

“The government was responsible for the policies. But the Norwegian settlers benefited from them,” she says.

Noble and wild

Norwegians knew about Native Americans long before they travelled there.

“There were a lot of books published, especially in the late 1800s, for children and young adults depicting Native Americans,” says Peterson.

For example, the book The Last of the Mohicans was published in Norway around 1830. A few years later, western novels became very popular.

The Native Americans were portrayed as wild and bloodthirsty, but also as noble and exotic.

"Diseases, wild animals, and Indians"

People in Norway also learned things from people who had already travelled to America.

In 1837, Ole Rynning, who had emigrated to Illinois wrote the travel guide True Account of America, for the information and benefit of the farmer and the common man.

America is inhabited by some wild nations who lived by hunting. These ancient inhabitants have been pushed back more and more because they would not adapt to a proper life and diligence, wrote Rynning (link in Norwegian).

He wrote that immigrants to the state of Illinois no longer needed to fear assault, because the Indigenous people had been deported. “Besides, these people are very good-natured and never start hostilities, unless they are offended.”

Felt at home with the Native American tribe

The Indigenous peoples and immigrants helped and traded with each other.

Olaus Fredrik Duus, a priest in Wisconsin, wrote in a letter home about a Norwegian woman who was lucky enough to get help from a Native American midwife. Everything was fine with the mother and child.

Anne Bjorli in North Dakota wrote that she had bought 600 kilos of fish from the Native Americans. She sold it for three times as much as she paid. It was the first time she had met so many Native Americans and saw how they lived in tents and log houses. 'The Indians were rather nice people to visit,' she wrote. She said she felt at home when she sat in front of their hearths, it was reminiscent of Norway.

Bjorli also commented on the political situation: 'They do not farm the land but have fed themselves by fishing and hunting. So as the land has gradually been taken from them, their sources of livelihood have diminished.'

She wrote about corruption among the agents who were supposed to administer payments and supplies. That meant the Native Americans often starved. 'It seems quite reasonable that they would rather fight for survival than die of starvation,' Bjorli wrote.

Most viewed

What the letters don’t say

There were many stories, exaggerations, and false rumours about Indigenous people, Bjorli wrote. This made immigrants afraid.

Deidre Whiteman compares this to today's enemy images in the American media.

“We are told to fear people we do not know. It was the same kind of campaign back then,” she says.

Bjorli's detailed description of the tribe she visited is an exception in the American letters sent home to Norway.

The late researcher Orm Øverland went through 1,600 letters that Norwegian immigrants sent home. Only 47 of them mention Indigenous peoples.

And they weren’t always in understanding tones:

Ole Haugerud wrote home after having been in a wilderness area in Canada. 'What we did see was unpleasant, the wild Indians fighting among each other like the wolves one may see in Norway.' He described them as wild animals in the forest.

Everyday life rather than unpleasantness

Historians have tried to understand why the Norwegians wrote so little about the Indigenous people in their letters home.

The answer may be that the Norwegians were not very skilled at writing and reading. Perhaps it was too complicated to describe everything that was different in America. They chose to write about the familiar and the everyday, according to Peterson.

The silence may also be due to the fact that the Norwegians did not want to think about the negative aspects of immigration. It may have been uncomfortable.

Norwegians killed in the war

In 1862, the Dakotas rebelled. The US Army was deployed. 500 settlers were killed, including several Norwegians.

“When you get trapped in a corner and you need to feed your children, you are going to attack. Unfortunately, the Norwegian settlers ended up in the crossfire between the Dakota people and the army,” says Whiteman.

The war changed the attitudes of Norwegians in both the United States and Norway.

Now the Norwegian settlers were portrayed as defenceless, but brave in the face of the Native Americans' cruelty.

“Before the war in 1862, they lived more or less side by side. But afterwards, they feared new attacks,” says researcher Anna Peterson.

In Norwegian newspapers and in letters home, the Norwegians discussed whether the rebellion was understandable.

“They wrote: ‘No wonder the Indians are angry. We took their land, and they want it back. But we don't want to give it back. What are we supposed to do?’ Others said that the Dakotas had no reason to be upset when the government took such good care of them,” says Peterson.

Authorities imprisoned hundreds of Dakota warriors. 38 were hanged. 1,000 women and children were interned, many starved to death.

Norwegians enter the reservations

Then Congress passed yet another new law.

The Daws Act of 1887 allowed immigrants to settle in the areas that had been set aside for Indigenous populations. Congress believed that the tribes did not do a good enough job working the land.

The authorities printed posters about free plots of land on the reservations.

“Of course, if you're poor and you see that, you're going to want to come get it ,” says Whiteman.

Many Norwegians moved in. On the Spirit Lake Reservation in Minnesota, they became neighbours with the Dakotas.

A lot in common

Sociologist Karen Hansen at Brandeis University in Massachusetts has studied this community. She points to similarities between the Dakotas and Scandinavian immigrants. Both groups were torn away from their homelands and had few resources. Both were exposed to the Americanisation policy, and they tried to preserve their own customs, language, and religious practices in the face of this pressure.

Deidre Whiteman can understand that the immigrants were passive.

“We had more in common with the immigrants than they realised. It was about survival. If you are an immigrant, you stay in your place. They are not going to try to disrupt, because they are afraid that the same thing will happen to them,” says Whiteman.

But there were also big differences, according to Hansen. The Norwegians were allowed to own their land, while the Dakota land was administered by the government. The immigrants could become American citizens, while the Indigenous population was excluded from citizenship until 1924.

These differences made it possible for Norwegian immigrants and their descendants to gain entry into society and make economic progress within a generation or two.

Don't want to talk about the past

There are 340 million people living in the United States.

Two million are Indigenous. And four million have Indigenous backgrounds combined with other ethnicities, according to the United States Federal Bureau of Statistics.

Deidre Whiteman believes in reconciliation.

“It will be a step forward. Reconciliation means acknowledging what happened in the past, but also moving forward as a people into the future,” says Whiteman. “Land returns to our tribes will be a step in the reconciliation process.”

But the return of land is a sensitive topic for the immigrants' descendants:

“Many organisations and institutions are very reluctant to have conversations about this topic. They say that the settlers got the land through legitimate means, sanctioned by the US government. They believe the immigrants did nothing wrong or illegal. Therefore, they shouldn't be made to feel bad or guilty or as participating in any kind of immoral activity,” says Peterson.

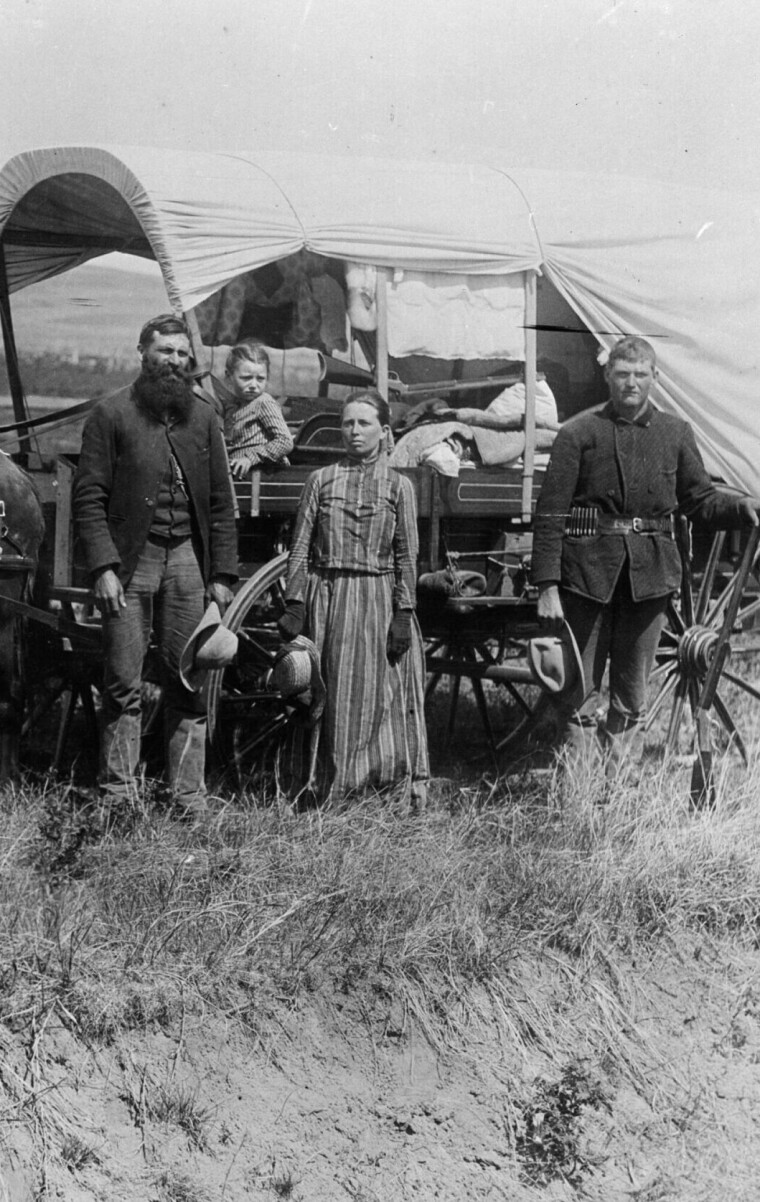

The photo at the top of the article shows immigrants from Europe on their way to a new country. It was taken in 1866, when many Norwegians travelled to the United States and headed to the Midwest to settle on free land. Photo: National Archives at College Park.

References:

Bergland, B.A. 'Norwegian Immigrants and 'Indianerne' in the Landtaking, 1838–1862', Norwegian-American Studies, 2000.

Hansen, K. 'Land Taking at Spirit Lake: The Competing and Converging Logics of Norwegian and Dakota Women, 1900-1930' in Norwegian-American Women: Migration, Communities and Identities, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011.

Øverland, O. (Ed.) 'From America to Norway: Norwegian-American Immigrant Letters', NAHA, 2014.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.