Norwegian emigrants built on stolen land. Kevin's family stood on both sides of the conflict

Kevin Jensvold's mother's family was exiled from Minnesota. His father's family moved in.

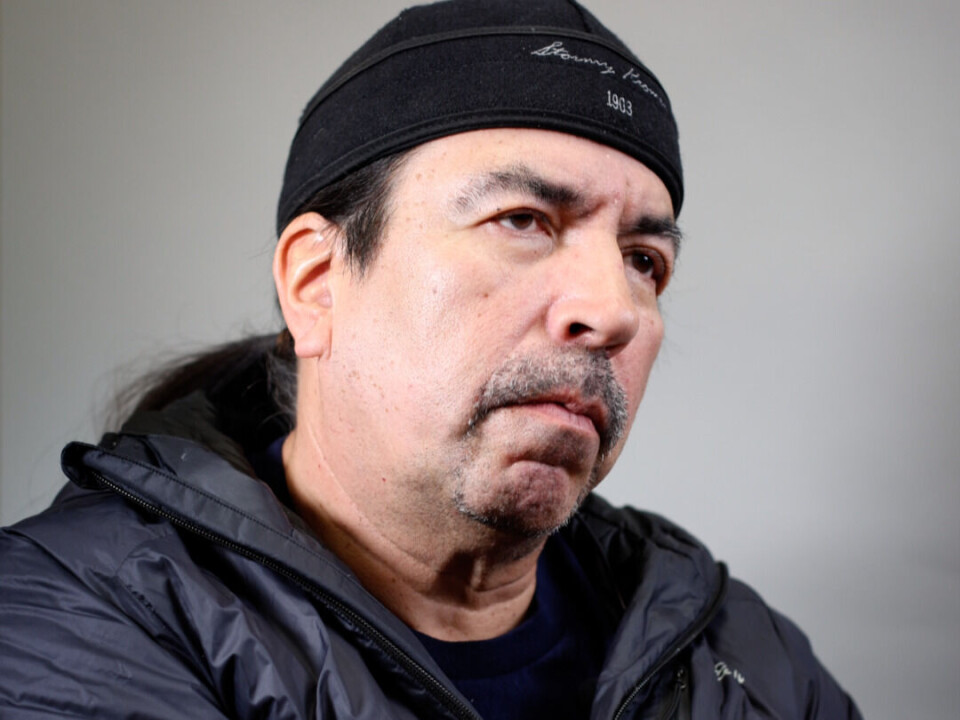

My name is Kevin Jensvold. My Dakota name is Petahoye To – the one who makes the fire blue. I live on the ancestral land of the Dakota tribe and the Yellow Medicine people, located in the Minnesota River Valley.

This is how the interview with Jensvold begins, which is featured in the exhibition at the Norwegian Emigrant Museum in Hamar.

Jensvold is of both Norwegian and Dakota heritage, the Indigenous people of Minnesota. He is a tribal chief in the area. His great-grandfather was the first white child born at Granite Falls, a town with many Norwegian-Americans. The town is located on land that belonged to the Dakota people.

Jensvold talks about the Dakota people's encounter with the white settlers:

We knew that the white people existed. We heard they were here. … I don't blame the settlers. They were seeking a good life, and in different circumstances, we might have met them as good neighbours. But they came at a time when our land was being stolen.

The Norwegians got Dakota land

The circumstances were not good for the Indigenous peoples of the US, says historian Terje Mikael Hasle Joranger.

He is the director of research and academic affairs at the Norwegian Emigrant Museum. When Science Norway asks Joranger to choose a favourite item from the museum, he chooses the interview with Jensvold.

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed, legally establishing the right to expel Indigenous peoples from their lands. The Dakota were forced into designated areas. This happened shortly before Norwegian immigration to the US began. Norwegians arrived in Wisconsin from 1840, and further west into Iowa and Minnesota ten years later.

"They always arrived on land that had already been taken from Indigenous people and mapped out by the government in a deliberate process to sell to immigrants," says Joranger.

In the 1860s, tensions escalated.

A four-month-long war

"The Indigenous population was under pressure. The government didn't keep the promises they made in a treaty to provide the Dakota with food and compensation for their land. Many were starving, while more and more settlers arrived to claim cheap land," Joranger explains.

The situation reached a breaking point in 1862.

A group of young and hungry Dakota warriors attacked a farm. That marked the beginning of a four-month-long war between the Dakota tribes and the US Army.

Up to 800 civilians were killed, many of them Norwegian immigrants. Even more were injured. Towns were raided and farms were burned.

The Dakota lost the war. The consequences were severe.

On both sides of the conflict

"The federal authorities annulled the treaty and forcibly displaced the Dakota further west. They simply drove them away," says Joranger.

Kevin Jensvold's family was on both sides of the conflict:

This is my family's story: He [the Norwegian great-grandfather] was born at the same time my mother's people, the Native Americans, were moving westward. This happened during the Dakota conflict in 1862, when we were driven out of Minnesota. My father's grandmother and grandfather told of Native Americans walking past the cabin they lived in for two or three days. So it is really a microcosm of my entire world – captured in that one moment.

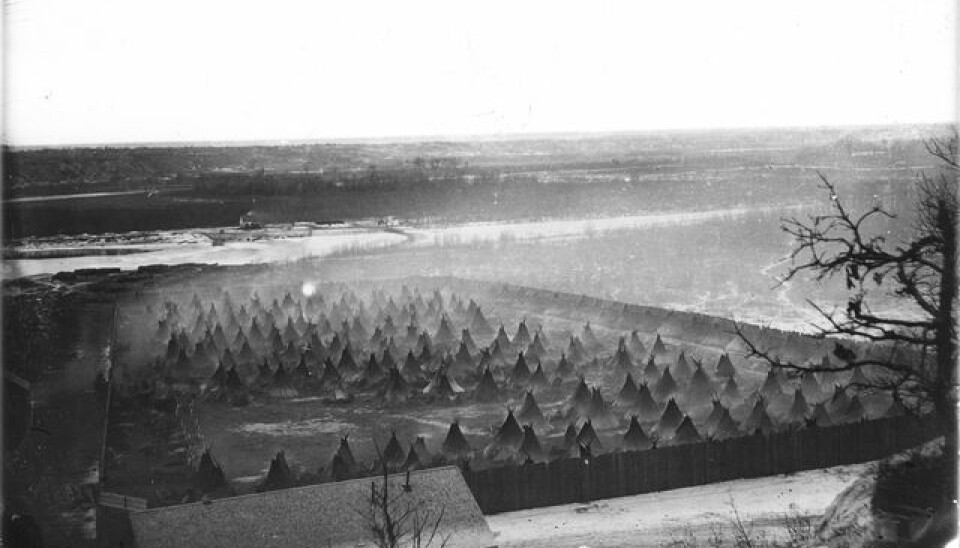

More than 300 Dakota warriors were sentenced to death in fast, chaotic trials. Many more were imprisoned, writes historian Karl Jakob Skarstein in his book about the conflict (link in Norwegian). One thousand women and children were interned, many of them starved to death.

Those forced westward arrived on barren land. Starvation followed them. It was all part of an intentional policy, says Joranger.

Land in exchange for a scalp

Many of those sentenced to death were eventually pardoned by the US president, but 38 warriors were hanged to the loud cheers of settlers.

Kevin Jensvold says:

The government hanged 38 of my relatives at a place called Mankato, Blue Earth, simply to satisfy the European desire to see the Natives disappear. … The government offered bounties on my mother's people. 75 dollars for turning in the scalp of an Native American. Then they raised it to two hundred dollars to keep settlers motivated to hunt Native people.

200 dollars was also the price the US government set for a section of land, which was 640 acres.

The Dakota were displaced and left without a home, while Norwegian settlers were given the opportunity to establish themselves.

Wanted to recreate Norway

"The Norwegians operated within the government's framework, but it came at the expense of Kevin Jensvold's mother's people. He is a descendant of both the dispossessed and the privileged," says Joranger.

Norwegian migration to the farming regions of the Midwest was largely conservative in nature, according to the historian.

"They left to preserve their way of life – moving from one farming society in Norway to another in the US. Norwegians settled close together. They recreated the Norwegian village," says Joranger.

The Norwegian presence is still visible in the region. Kevin Jensvold shares:

Old cabins around here clearly show signs of Norwegian influence in their construction. They were likely trying to recreate a sense of home and belonging to the place they came from.

Most viewed

The important land

The Norwegians were far less urban than, for example, Danes and Swedes. Their connection to the land ran deep.

"Of all immigrant groups, Norwegians were the most closely tied to the land. It had status. It was something they could pass down through generations, a legacy within their own family," says Joranger.

Kevin Jensvold:

We never understood the European concept of staying in one place. Even today, it makes little sense. Instead of moving with the resources, we import them. Today, we are dependent on being in a fixed location. But that's not how the world was created.

For Indigenous peoples, land is seen as a shared resource – something collectively owned by the community. You are not meant to take more than you can carry.

This stood in stark contrast to how the authorities viewed the land.

"Norwegians became part of a larger strategy by the US government: To populate and build the country using immigrants," says Joranger.

What did the immigrants know?

Historian Joranger has studied three travel guides written for Norwegians considering emigration to the United States. What were they told about the country they were heading to and about those who lived there?

Before the Dakota uprising in 1862, the guides said little about Indigenous people.

They were described as 'wild,' but not dangerous: 'They are very good-natured, and never begin hostilities when they are not affronted.'

News of the killings of Norwegian settlers during the conflict reached Norway and sparked fear.

One travel guide mentions 'the great Indian scare' after 1862. It stated that Europeans had nothing to fear if Indigenous people were treated as equals. The book criticised the government’s repeated attempts to deceive, suppress, and insult Indigenous communities.

Kevin Jensvold:

Did settlers know about the agreements that were not upheld by the US? I’m not sure they were willing to ask those questions. All they saw were the opportunities in front of them.

Lost the farm because of marriage

Even in more recent times, the relationship between immigrant descendants and Indigenous people has been complex. Kevin's father is Norwegian-American, his mother is Dakota. His father inherited the family farm, but after the marriage, the family reacted with outrage.

"He was disowned and forced to give up the farm. The family couldn’t bear what they saw as the shame the marriage brought," says Joranger.

Kevin's parents remained in the area. When he was growing up, Norwegian was still spoken in the streets of Granite Falls. One of his Norwegian uncles stayed in touch, brought Kevin lutefisk, and showed him chests brought over from the homeland.

Kevin Jensvold:

If I want my mother's culture to be respected, I also have to respect my father's culture.

Taking responsibility

Kevin Jensvold wants the story of the Dakota people's displacement to be acknowledged:

The people living today are not responsible for everything that happened, but they are responsible for acknowledging that it did.

He believes it is important to understand that the land people live on today came at a cost to his mother’s people:

I truly hope that the price my mother's people had to pay was worth it to those who took the land. That their lives became better because of it, because ours were damaged by it.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.