The Nordland boat is the legacy of the Viking ships: "We were probably close to death many, many times"

The Nordland boat was built using the same clinker method as the Vikings. It wasn't necessarily very safe.

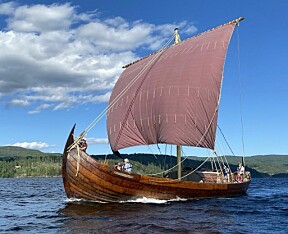

“You can see how it resembles the Viking ships,” says Eyvind Bagle. “This is a boating tradition that goes back hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.”

Bagle chose a large Nordland boat when sciencenorway.no asked him to describe one interesting item from the Norwegian Maritime Museum. Bagle is a conservator in the museum’s research department.

The boat was built in 1901. It is as long as a large bus and close to 14 metres in length. It has six pairs of very long oars, which as many men rowed when there was no wind.

The fembøring, as this type of boat is called, was primarily sailed — and used for fishing.

Ole Benjaminsen was the boat's first owner. He lived in Helgeland in Nordland and was a fisherman. He probably bought it for NOK 415, roughly 39 USD.

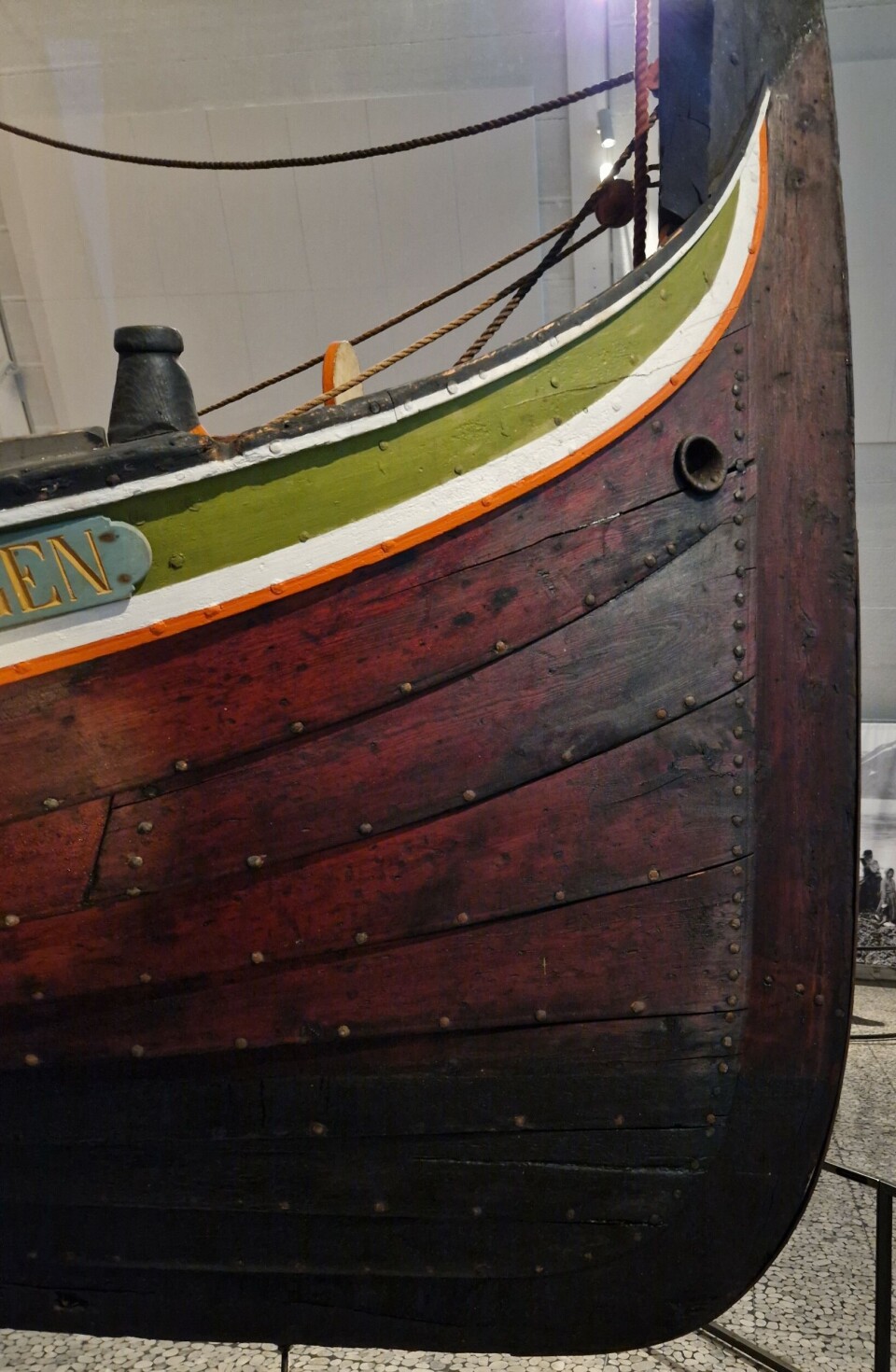

Benjaminsen was a very religious man and knew his Bible. He christened the boat ‘Opreisningen’ - The Resurrection. It’s a reference to a verse in the Book of Psalms that describes how those who believe in God will be lifted up into the kingdom of heaven.

The boat's name will later take on new significance.

The legacy of the Vikings

The Viking ships were built using the clinker method. So was the fembøring.

First they bent the keel. This means that the hull was built first.

“Then the hull planks were placed on top of each other, so that they overlap. They were then fastened together with rivets, which were riveted to a metal plate,” Bagle said.

The boat lay low in the water. It also had no deck. This meant that it took on water easily.

It was a hard life, especially in the winter when they constantly had to cut the boat clear of ice, an 80-year-old, unnamed fisherman told the newspaper Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende in 1919: ‘We had no other way to power the boat then than sails and oars, and we were probably close to death many, many times, frozen and stiff in the open Nordland boats. I can't describe everything a fisherman suffered on the sea back then...’

Social scientist Eilert Sundt, who worked for public education and social reforms in the 19th century, believed the boat was dangerous for fishermen.

He was particularly concerned about working conditions for fishermen, farmers and workers.

700 people drowned each year

“Sundt was concerned with mortality in Norway. He calculated that 700 people drowned in Norway every year, with a population that was half of what it is today,” Bagle said.

In comparison, 88 people drowned in Norway in 2022, according to the Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue.

“A third drowned in the northernmost counties, where the fewest people lived,” Bagle said.

Sundt believed that the many drownings had to do with fishing boats such as ‘Opreisningen’. When the sea swells were high and the waves crashed over the low-lying boat, the fishermen had no other protection than bailers.

“Whether the fembøring was a good or bad boat has been long debated, in a debate that has continued right up to today,” says Bagle.

Time is running out for the boat

The fembøring was built based on tradition.

“The knowledge was inherited. They built the boats as their fathers did. Eilert Sundt thought they shouldn’t keep building them as they did,” says Bagle.

The ‘Opreisningen’ was difficult to row, so Ole Benjaminsen bought a new, lighter boat in 1908. He sold the old one to two cod fishermen, who after a few years sold it to two brothers, who may have used it for catching seals.

The fourth owner was Petter Olsen Flæsa from Tjøtta, in Helgeland. He used the boat to transport wood and materials.

But time was running out for the fembøring. They were being replaced by faster and lighter boats with decks. Eventually motorboats would arrive on the scene.

“The transition from fembøring rigs to scows with engines was slow. In the 1920s, the authorities came up with support schemes to get the fishermen to buy new and better boats,” Bagle said.

Then the idea of a museum was born.

‘Norway's proudest vessel’

Thorolf Holmboe was a painter and interested in the old boats. In 1926, the Oseberg ship had been given a place in the new Viking Ship Museum on Bygdøy, a peninsula on the west side of Oslo. Now it was time for the Nordland boats, Holmboe wrote in the national newspaper Aftenposten the same year:

‘... There is another boat that no one has thought of building any kind of boathouse for, not from corrugated iron or cement. I mean Norway's proudest vessel, the fembøring.’

Holmboe was concerned about preserving the boats. In 20 years there won't be as much as a splinter left, because the now out-of-date fembøring will be chopped up for firewood or left on land to slowly rot, he wrote, and called for action:

‘Should there be a stout, tarred fembøring with a tanned sail left up north, then let's get it and put it in the building with the Viking ships. Its importance for business and social life in the north has been too significant, its image in the landscape too characteristic, for one to simply let the fembøring disappear forever.’

The ‘Last Viking’

The owner of Tiedemann's tobacco factory took action. He wanted to pay the costs of getting a fembøring to the Norsk Folkemuseum, an open air museum in Oslo.

Now it was just a matter of finding a boat that was in good enough condition for the trip to Oslo.

Petter Olsen Flæsa at Tjøtta had stopped using ‘Opreisningen’ for transport. He was in the process of turning the boat into a house for eider ducks, according to the newspaper Bodø Tidende 1927. But he was willing to sell.

First they had to get the boat ready to travel. Everything had to be in top condition for the month-and-a-half trip down the coast, with stops in many towns and places.

It was partly cultural preservation and partly PR for Tiedemann's tobacco.

In August 1927, the old fishing boat enters the Oslo fjord with its large, brown, patched sail. It attracts a lot of attention.

There was a tightly packed mass of spectators who had gathered to see the fembøring sail in. This boat ‘whose last voyage had attracted the attention of the Oslo journalists, and they had then gathered in a cluster, these men of the press, to take a close look at this last representative of the Viking boat's descendants, ‘The Last Viking’, the newspaper Bodø Tidende reported in 1927.

House built for a boat

A number of sailboats and motorboats followed ‘Opreisningen’ as it sailed inland.

It was ‘a strange new sight, perhaps never before been seen down in these surroundings," according to Bodø Tidende.

The boat first found its home at the Norsk Folkemuseum. But when the Maritime Museum, now the Norwegian Maritime Museum, got its first building on Bygdøy in 1958, the boat was moved there.

“The boat hall was sized for the ‘Opreisningen’,” says Bagle.

It’s still there.

And the name fits, according to a 1927 article in the national newspaper Dagbladet:

“It's called ‘Opreisningen' (the Resurrection) — a downright symbolic name for the boat, which will preserve the entire proud memory of the fembøring for posterity.”

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------