What did the Vikings really think about pregnant women?

Archaeologist Marianne Hem Eriksen has been searching for traces of pregnant women in the Viking Age. The fact that she found almost none tells its own story.

Helgi Harðbeinsson has just killed the husband of the pregnant Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir.

He drags his bloody spear over Guðrún's clothes and across her belly and says, 'I believe that beneath this garment rests my own death.' And sure enough, he turns out to be right – the foetus in the womb grows up and avenges his father.

The story from the Saga of the People of Laxardal is one of the few tales about pregnant women in the Viking Age that Marianne Hem Eriksen has managed to uncover.

Most viewed

At that time, the average life expectancy was just 40 years.

"Researchers believe most women spent much of their lives either pregnant or breastfeeding. It wasn’t something they could control the way we can today," says Eriksen.

Even so, pregnant women are barely mentioned in the historical sources.

Mostly men, and some elite women

Eriksen's research group searched for pregnant Vikings in three places: in literature (sagas and legal texts), in burial finds, and in art. The results were recently published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Among thousands of depictions of people in Viking art, they found just one possible image of a pregnant woman.

The pendant, found in a woman's grave in Aska, Sweden, shows a woman who appears to be holding her arms around a pregnant belly.

"Objects like this are often interpreted as amulets or representations of gods. They’re not considered literal portrayals of everyday people," Eriksen points out.

Most people in the Viking Age probably never saw an image of a human being that resembled themselves, according to the archaeologist.

"There's a strong dominance of male figures in the artwork, and the women who do appear are typically elite – possibly goddesses or mythological creatures. It's a very narrow visual world," she says.

And one that, quite clearly, showed little interest in pregnant women.

Some foetuses are people, others are defects

Pregnant women are largely invisible in saga literature too, according to the study. They occasionally appear in the background, but rarely as central figures.

The language used to describe them leans towards the negative. A pregnant woman is portrayed as sick, incomplete, unwell, and heavy.

The story of Guðrún is interesting because it reveals underlying social structures, according to the archaeologist.

"In this case, the foetus is already considered a social being before birth. The unborn child is part of alliances and blood feuds, politics and revenge, while still in the womb," says Eriksen.

But when it comes to an enslaved woman, the foetus is seen as a defect in a body that's up for sale, according to legal texts.

Freydís with the breasts and the sword

In another tale from the Saga of Erik the Red, Freydís Eiríksdóttir is pregnant and under attack.

"It's a kind of Amazon-like story," says Eriksen, referring to the legendary female warriors of Greek mythology.

Freydís is alone and unable to flee because of her pregnancy. She picks up a sword and exposes her breasts. Then she strikes her breasts with the flat side of the blade, scaring the attackers away.

Eriksen sees a connection between this story and the Aska pendant depicting a pregnant woman – she appears to be wearing a helmet with a clover-shaped nose guard.

"Pregnant women weren't just passive. At least in Viking art and literature, it was possible for a pregnant woman to be a warrior or associated with weaponry," she says.

Not buried with their infants

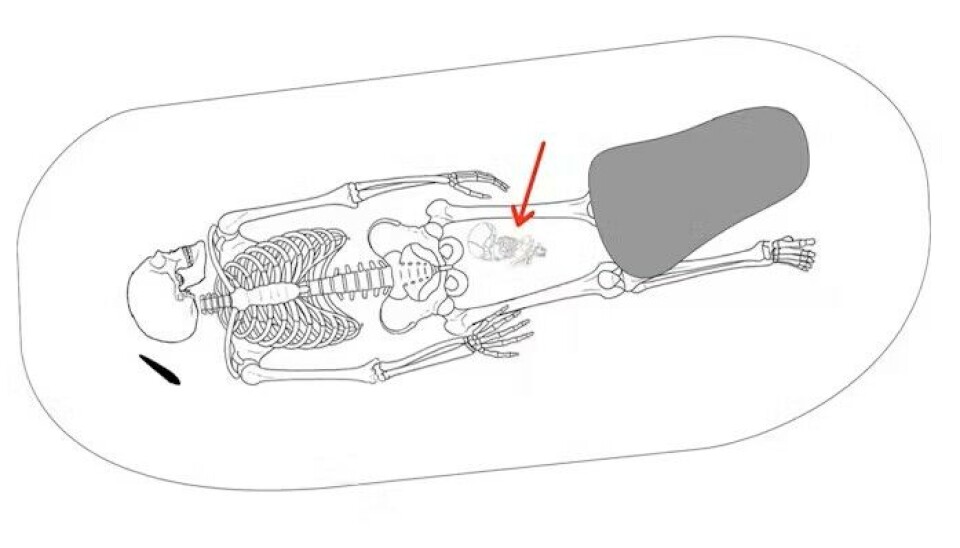

The last place Eriksen and her team searched for pregnant Viking women was in burial grounds.

They reviewed every major catalogue of Viking Age graves, covering excavations from the 1800s up to the present.

They looked specifically for women of reproductive age buried with newborns. Women who may have died late in pregnancy or during childbirth.

Out of thousands of graves, they found only 14 possible cases.

"That's a very small number. Even though the quality of the documentation varies – not everyone was careful about documenting remains of infants – it's still strikingly low. Especially when we know maternal mortality during pregnancy and childbirth was very high in pre-industrial societies," says Eriksen.

Infants in postholes

This may relate to something Eriksen has researched before – people's homes during the Iron Age and Viking Age. In those studies, she found newborns and infants not given typical burials, but instead placed in postholes, buried inside houses, in wells, and in pits.

"Children are consistently underrepresented in burial records throughout this entire period. They were likely not buried in the same way as adults," says Eriksen.

Regardless, there’s no evidence that Vikings had a tradition of burying mothers and infants together.

"Based on what we've found, it doesn’t seem to have mattered to them to keep mother and child together in death. That in itself is revealing. It looks like the children were separated and treated differently," she says.

In other periods, burying mother and newborn together was common. In Anglo-Saxon societies in England, around the same time as the Viking Age, this was a typical practice, Eriksen explains.

In those graves, archaeologists also often find evidence of what’s called a 'coffin birth.' When heavily pregnant women were buried, the foetus was sometimes found between their legs, having been expelled after death by natural bodily processes. Eriksen finds little evidence of this among the Vikings.

The personal was political back then too

Archaeology has traditionally paid little attention to women and their lives, according to Eriksen.

"The Viking Age is incredibly romanticised and popular, and there are still so many stereotypes influencing both the research itself and the questions we ask," she says.

And at the same time, it turns out that people in the Viking Age also paid little attention to at least this part of women's lives. Which is a discovery in itself.

"Reproduction is absolutely fundamental to society in every conceivable way. And yet it's deeply political. We can see that in the limited material we have, and in the lack of focus on women's lives in saga literature," says Eriksen.

"Today we recognise that issues like when a foetus becomes a social being, or the right to reproductive autonomy, are political. But when we look at the past, we tend not to see it that way. Politics is usually defined as laws or capital-H historical events, like battles and coronations," she says.

Asking questions no one else thought to

"This study is part of a series of exciting work Eriksen has done in recent years," says Lisbeth Skogstrand.

She is an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Bergen, with a focus on gender in the Bronze Age and early Iron Age.

"Eriksen is innovative and bold enough to ask questions that few others have even considered," she says. "None of us would exist without pregnancy. It's so central, so important, and such a major part of many women's lives."

Skogstrand points out that even as recently as our great-grandparents’ time, having 10–12 children was not unusual.

"You were either pregnant or breastfeeding. It's a huge paradox that this doesn't get more attention," she says.

The absence of pregnant women is a deliberate choice

Skogstrand believes Eriksen and her colleagues have done a great job trying to find traces of pregnancy in the archaeological material.

"14 graves that may contain a mother and newborn or unborn child. That's shockingly low compared to what we'd expect," she says. "And just one pendant. Pregnant women are virtually absent from Viking iconography."

And that absence is a significant finding in itself, Skogstrand agrees.

"This is a deliberate omission. It’s not like someone just forgot that people get pregnant. That absence carries meaning," she says.

The Viking Age is often portrayed as hypermasculine.

"Certain aspects of Viking culture were heavily focused on masculinity," says Skogstrand. "And the masculine gets more attention because it's clearly present in both the written sources and the archaeological material. Eriksen is searching for what isn't visible. She's not interested in easy answers – she's challenging herself and the rest of us."

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Eriksen et al. Womb Politics: The Pregnant Body and Archaeologies of Absence, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2025. DOI: 10.1017/S0959774325000125

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.