A mystery lies hidden behind the cladding of this stave church

Norway was by no means lagging behind in the Middle Ages, says art historian.

An old, disused portal stands out from all other preserved stave church portals.

"Foliage wraps around the arch so it disappears, restless leaves burst forth, leaf stems twist around each other and transform into columns. It's unique in a Norwegian context," says art historian Margrete Syrstad Andås at NTNU.

She is the most recent to study the portal, which has fascinated several generations of art historians.

Andås has written a chapter about the portal in the book Rødven stavkirke (Rødven Stave Church).

Quite unique and strange

'It doesn't resemble anything else we have preserved, it doesn't fit into any known categories, it seems impossible to date, and the risk of drawing the wrong conclusion is high. On the other hand, it’s such an intriguing scholarly puzzle that it’s impossible not to write about it,' Andås writes in the chapter.

According to her, nothing like it exists – neither in Norway nor abroad.

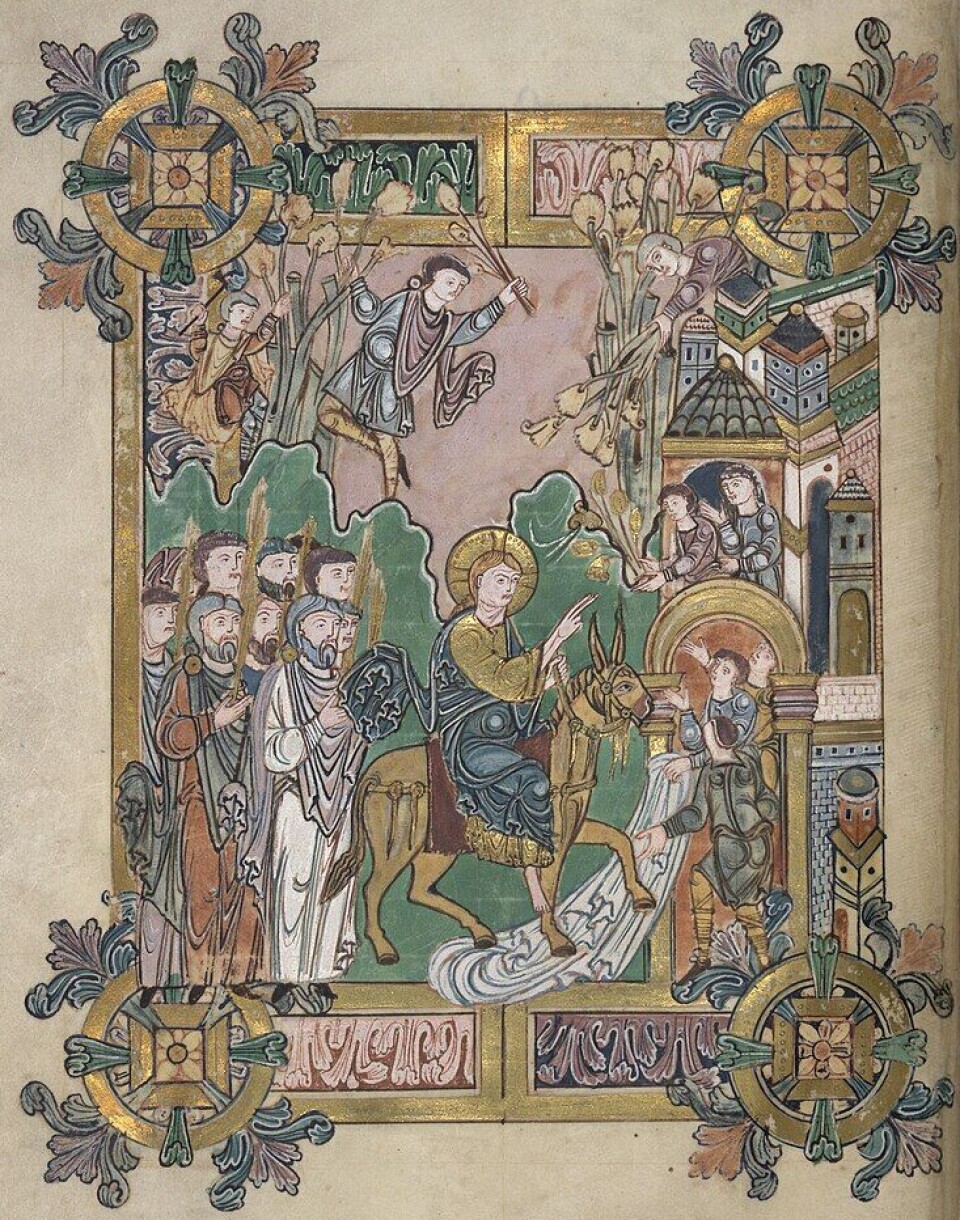

She believes the decorative style is linked to early Anglo-Saxon art. In richly illustrated books from the Winchester area around the year 1000, foliage is often used to frame the illustrations. These resemble the foliage from the portal at Rødven Stave Church.

Andås considers it unlikely that the portal was carved as late as 1100. She proposes a wide possible timeframe, but suggests that around 1070 is a reasonable estimate.

Among three-dimensional artefacts, she finds a stylistic connection with an old bishop’s staff.

No known examples

The surviving part of the bishop’s staff from Alcester, now kept at the British Museum, is carved from walrus ivory. It features intricate scenes of the crucifixion and the resurrection.

What fascinates Andås most, however, is the foliage. Its design is nearly identical to elements on the Rødven portal.

Dated to around 1020-1050, the staff is considered an Anglo-Saxon creation, writes Andås.

How could we have been influenced by the Anglo-Saxons in Norway?

Tiny details

There is no preserved evidence that this same style existed in Anglo-Saxon architecture.

Still, Andås is convinced it reflects a clear tradition, one that carvers did not just invent.

She believes the person who carved the Rødven portal had carved the same motif many times before.

"The foliage is distinctive," she says.

She points to tiny details, such as veins in the leaves.

"The carver clearly took great care, using a plane that highlights the narrow contours," she says.

It has long been assumed that Norway was slow to adopt new artistic styles – ideas supposedly arrived in the cities first, then reached rural areas a generation later.

"That may have been true in the 1800s, so assuming the same for the Middle Ages isn't unreasonable," she says.

But during the Viking Age, Norway was far more connected and active. This fits with the theory of Anglo-Saxon influence in Norwegian woodcarving.

Could have learned from the Anglo-Saxons

"The Vikings were deeply involved in civil wars in England. Olaf III, or Olaf Haraldsson, even joined his father, Harald Hardrada, on expeditions there. That tells us something about their mindset," says Andås, and continues:

"These were people with the means to cross the North Sea and to bring skalds along with them, possibly artists too."

Most viewed

A skald was someone who recorded history, usually among the king's men.

"It’s not certain the carver came from England. They may have learned the style from someone else," she says.

It is also possible that an Anglo-Saxon woodcarver created multiple portals in the same region.

The door to salvation

The portal that stands at Rødven today is incomplete. Only the vertical side posts remain from the original structure. Andås therefore believes the portal has been moved, possibly more than once.

“We have to assume that reusing valuable artworks was common,” she says.

The same is true of the Urnes portal, which was originally made for an earlier stave church on the same site. It looks quite different today, which highlights the importance of preserving craftsmanship. Art historian Kjartan Hauglid talked about this in an article on Science Norway in 2024.

"The portal represents Christ – it's the door to salvation," says Andås.

She believes the portal was once painted.

"It was most likely green, as crucifixes often were," she says.

A crucifix is a sculpture of Jesus nailed to the cross.

According to Andås, some of that same symbolism is reflected in the foliage carvings.

The essence of being human

"The portal represents eternal life, what awaits those who enter through it," says Andås.

Everything that happens in the church begins through that doorway, she explains.

The portal was where suspected criminals stood to declare their innocence. In the 11th century, special rituals were held when a woman returned to church after childbirth. She was formally brought back following what was seen as sexual sin and impurity.

"Childbirth brings you face to face with the essence of being human. Imagine how relieved people were when the mother had survived and was brought into the church," she says.

Such powerful memories are tied to objects like the Rødven portal, says Andås.

"Such artefacts live on. They connect families and generations. The portal is a central feature of the church," she says.

Shaped by local conditions?

"There was extensive contact between Norway and the British Isles over centuries, with cultural and linguistic exchanges flowing both ways," says Karoline Kjesrud.

She is an associate professor at the University of Oslo.

"It's interesting to connect the ornamentation of the Rødven portal to Anglo-Saxon style and influence from the west," says Kjesrud.

She says Andås' dating of the portal is exciting.

Kjesrud believes the article encourages future scholars to study plant ornamentation in church portals more closely:

"As a reflection of both cultural influences and local expressions and variations."

It's not a given that such ornamentation always drew on foreign influence, according to Kjesrud.

"Perhaps plant motifs were shaped just as much by local conditions?" she wonders.

Plant motifs on runestones

Kjesrud notes that the plant designs on some stave church portals may reflect local flora or artistic traditions, not necessarily direct foreign inspiration. She speaks in general terms, and not specifically about the Rødven portal.

"It would be interesting to compare the plant motifs on the Rødven portal with those on other objects from the 11th century," she suggests.

According to Kjesrud, there are almost no examples of such designs from before Norway’s Christianisation. But from around the year 1000, plant motifs became powerful symbols of the Tree of Life, victory over death, and eternal life.

Runestones are the oldest known Norwegian monuments featuring plant ornamentation. Kjesrud points to the Dynna, Alstad, and Vang stones, all dated to the 900s and 1000s and found in inland Norway. These stones show no obvious connection to western influences, says Kjesrud.

"They also feature interwoven plant patterns, some of which bear a resemblance to the carvings at Rødven," she says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Borgen, Linn Willetts., Dahle, Kristoffer and Langnes, Mads. (Eds). (2024). Rødven Stave Church. Romsdalsmuseet, Fortidsminneforeningen and the Institute for Comparative Cultural Research.

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.