When Norwegians came to America, they didn’t have time to let the timber dry

Many Norwegians succeeded in America. The houses they built are evidence of this.

The Norwegian census in 1910 showed that there were 2.2 million people in Norway.

In the US census of the same year, 700,000 people said they had Norwegian ancestry.

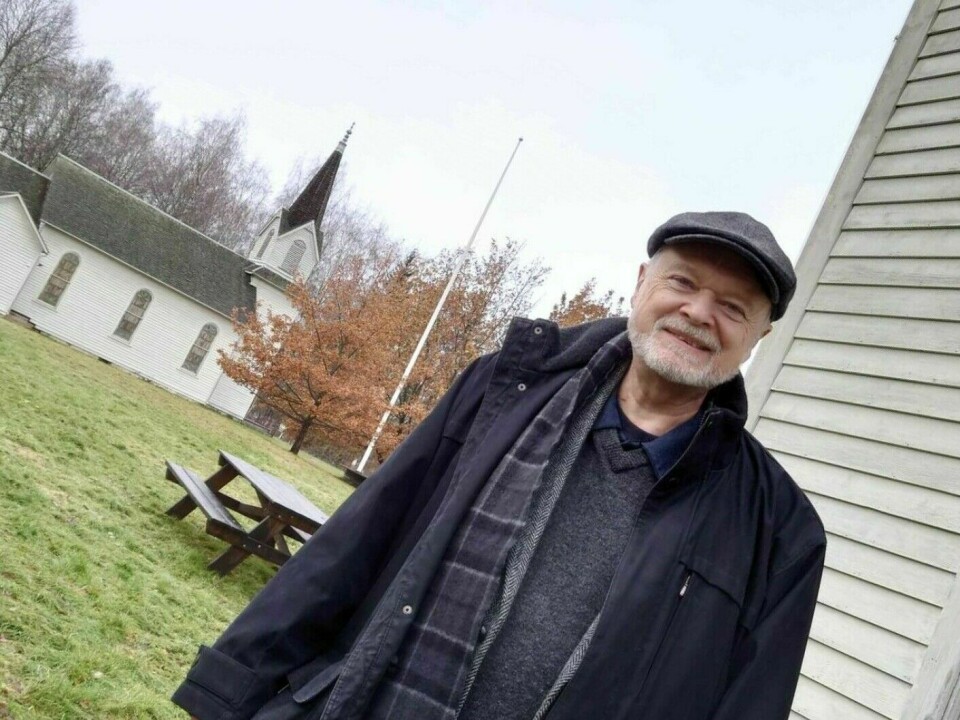

“You could say that a quarter of all Norwegians lived in the USA in 1910,” historian and author Knut Djupedal says.

Most viewed

They have left their mark. Some of them are collected at the Norwegian Emigrant Museum, where Djupedal was the museum director for 20 years.

The 75-year-old came to America with his family in 1955, at seven years old. But Djupedal moved back to Norway. He recently released the book Nordmenn bygger I Amerika (Norwegians building in America).

Not everyone became farmers

The Norwegian Emigrant Museum consists of eight buildings brought to Norway from the USA.

“These houses are a large, permanent exhibition intended to initiate discussions about emigration. Not just to the Midwest, but everywhere,” Djupedal says.

All the buildings at the museum are indeed from the Midwest, but that doesn’t mean all Norwegians settled there.

“There’s a kind of accepted truth that all Norwegians went to the Midwest, became farmers, and never came back,” he says.

It’s wrong – or at the very least, a truth with significant modifications, according to Djupedal.

History Professor Nils Olav Østrem at the University of Stavanger agrees with Djupedal that many of them continued with it: Not all of them headed towards the Midwest.

Some exchanged city life in Norway for city life in the USA.

“Young emigrants often had a city stay in Norway first,” Østrem says.

There were many of them. You can read more about them in this sciencenorway.no article.

Windows eventually came

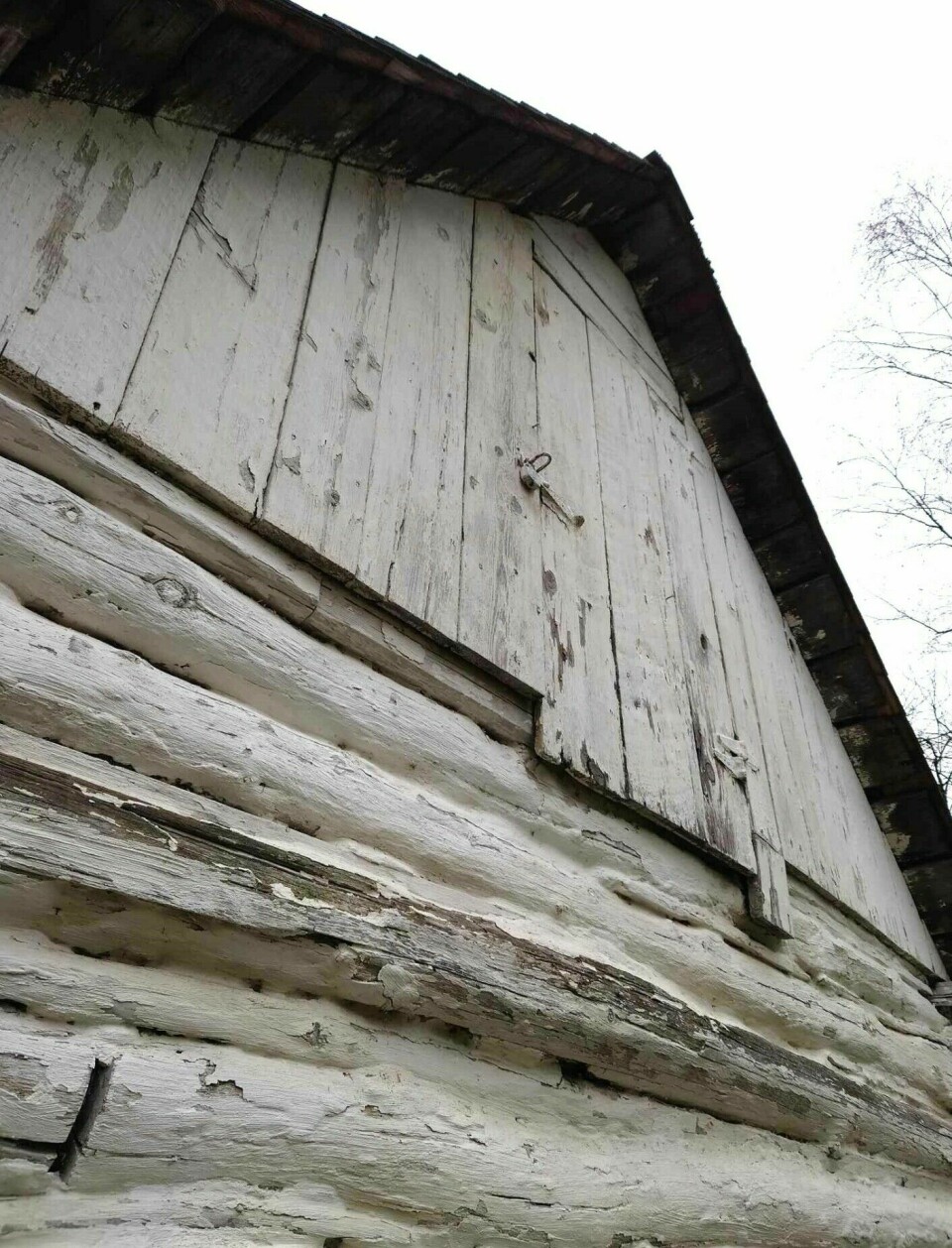

The oldest residential building at the Emigrant Museum is the Kindred House. It was built in North Dakota in the 1870s. It serves as a classic example of a pioneer house, essentially the first house a Norwegian emigrant built on the prairie to quickly get a roof over their head.

The Kindred House hastily constructed with raw timber. There was no time to let it dry. This is evident in the way the timber in these structures has shrunk. Apart from this, it bears a resemblance to traditional Norwegian log houses.

This small log house features windows, something that was frequently absent in the early homes of pioneers.

It seems the owner of Kindred House was able to afford windows later. These are factory-made.

Windows and doors could be ordered from the factory and picked up at the nearest railway station. Then it was just a matter of sawing suitable holes in the walls and placing them.

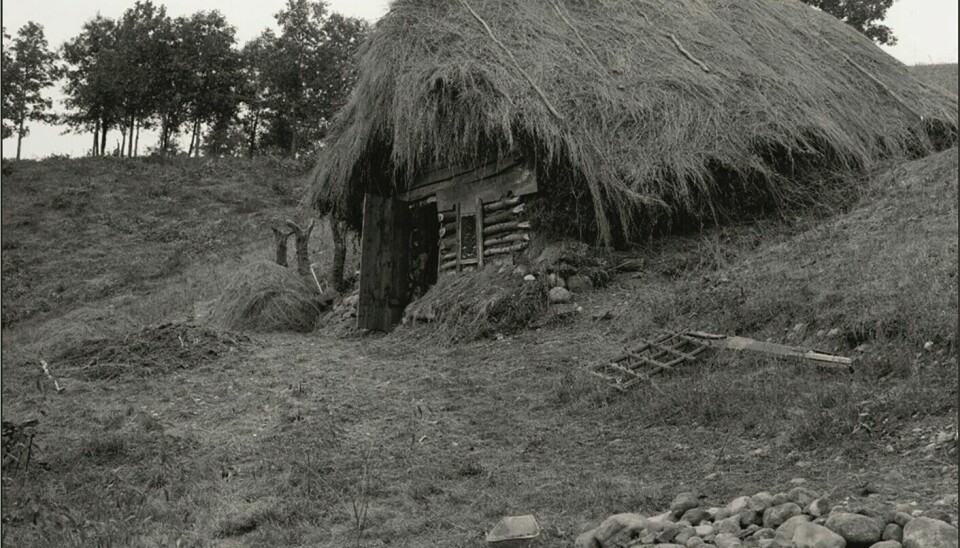

Others made themselves an earthen hut as their first shelter.

Dirt floor and wood stove

Dugouts were huts dug halfway into a hill.

‘Such dugouts were by far the most common first dwelling on farms everywhere in the American Midwest,’ Djupedal writes in his book.

It's said that certain families lived in these for several years, managing to make them relatively comfortable.

These structures, topped with temporary roofs, could accommodate a wood stove, a few beds, and cupboards.

Better housing resulted from school and church

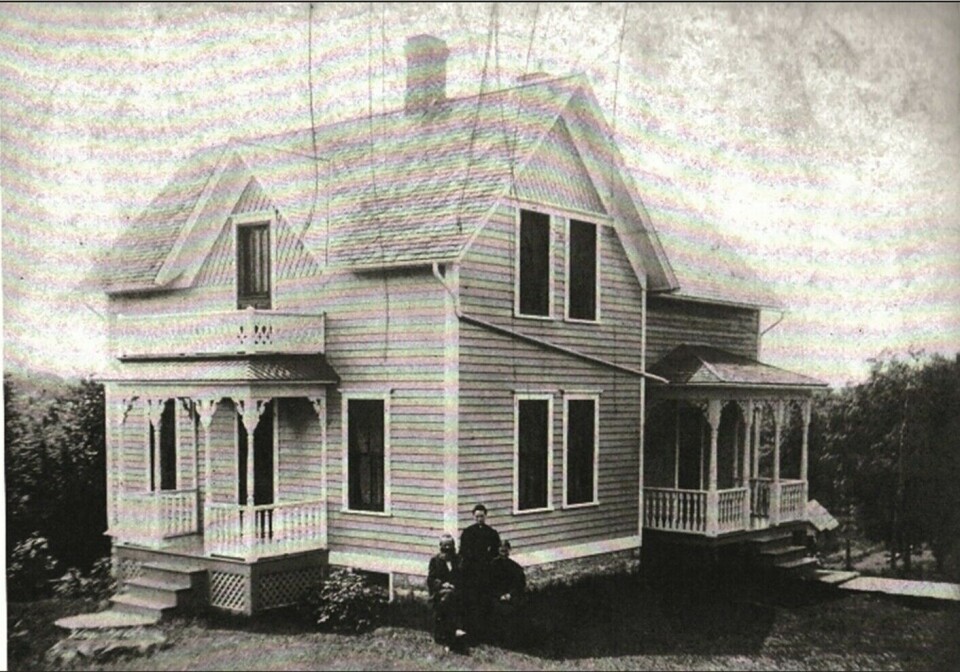

The next generation's houses were a bit larger and better, like the Bjorgo House. It was built by a Norwegian-American in 1902.

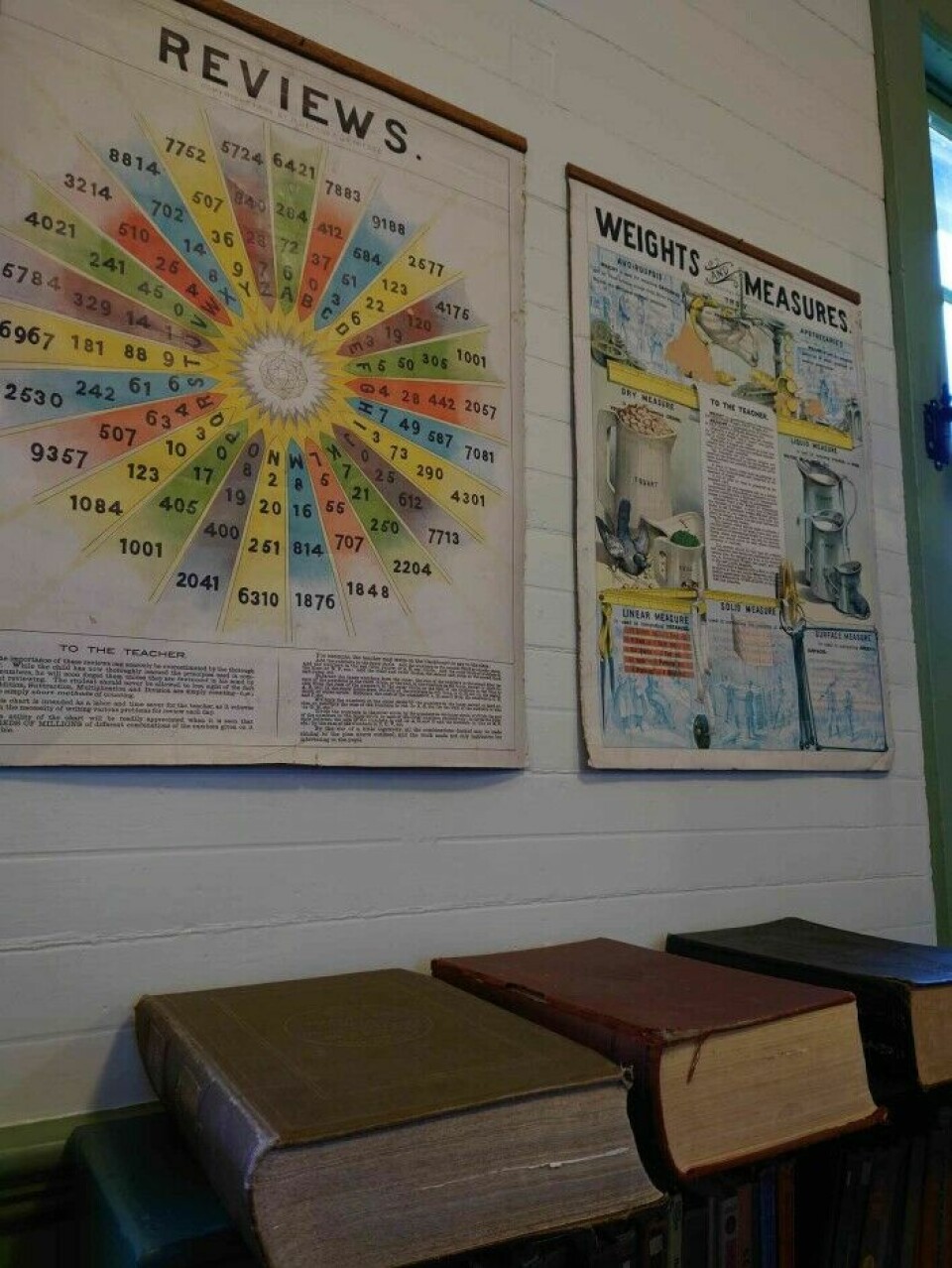

School buildings and churches often appeared around the same time as such residential buildings.

Finally, it became possible to invest in the community beyond just the bare necessities.

The Bjorgo House consists of two floors plus a basement with entrance at ground level – a kind of lower ground floor.

The first owner of the property was the Norwegian Hans Syverson, before this house was erected.

Djupedal writes in his book that it is highly likely that Syverson's first house on the site was a dugout with a dirt floor.

It's possible that this dugout was eventually converted into the basement of the Bjorgo House. The presence of an entrance on one side of the basement seems to indicate this.

It was not always feasible to build both a school and a church at the same time. In such cases, the school building was used as a school church, and community centre.

“It requires a certain level of social organisation to achieve this,” Djupedal says.

Easy to expand upon

The Bjorgo House was constructed using a timber frame technique and in so-called Carpenter Gothic style. This was typical for small wooden buildings in North America at that time.

Externally, the house is most elaborately designed around the entrance. This was a house intended to be easy to expand upon if the owner could afford it.

In contrast to the columns at the entrance, the back wall was as simple as possible. It has just a simple door and a window. The door could later be used as an entrance to a new wing. However, this did not happen with the Bjorgo House. The owners probably couldn't afford it.

Ran out of pine

When European immigration to the USA accelerated in the 19th century, a tremendous number of trees were cut down.

Like many other houses, Bjorgo House was built of Weymouth pine. By the turn of the 20th century, it was almost extinct, Djupedal writes in his book. Bjorgo House was therefore constructed when the supply of sought-after pine began to dwindle.

The construction in light timber framing is very similar to that used in new wooden houses.

Djupedal writes that it became common in the USA in 1830. 120 years later, around 1950, it became widespread in Norway.

Nostalgic relationship with family farms

Djupedal describes Bjorgo House as a testament to a successful life in the new country. Even today, many look back on life in houses like Bjorgo House with nostalgia.

The house stood on a family farm.

By today's standards, the family farms were small. They operated with horses, oxen, and manual labour. The goal was to produce enough food for the family, with a surplus that could be sold.

The surplus often consisted of corn or wheat. It could also include eggs, milk, or meat – for example, from cattle and pigs.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Djupedal, K. ‘Nordmenn bygger i Amerika’ (Norwegians building in America), Norwegian Emigrant Museum, 2023.