New model could explain old cholesterol mystery

Saturated fats increase cholesterol. And high cholesterol is linked to heart disease. But why are researchers unable to show that saturated fat actually leads to heart disease?

Simply put, this is the very heart of the years-long disagreement over saturated fat and heart disease:

The data doesn’t point in the same direction.

On the one hand, an overwhelming number of studies show that saturated fats, like butter, bacon fat and coconut fat, increase the levels of LDL cholesterol in the blood.

It is also well documented that high cholesterol is linked to heart disease. People who get heart disease are more likely to have high LDL cholesterol, compared to those who do not develop heart disease.

Researchers have thus drawn a logical conclusion: a lot of saturated fat in the diet produces more cholesterol, which in turn increases the risk of heart disease.

But this has been surprisingly difficult to prove. When researchers look for direct links between saturated fat and heart disease, they often don’t find much.

Even in long-term trials where groups of participants eat foods with differing amounts of saturated fat, no differences emerge between groups in how many people become ill or die of heart disease.

So what’s the story? Are we getting sick from saturated fat or not?

The pieces of the puzzle don’t fit.

Marit Kolby Zinöcker is an assistant professor at Bjørknes University College in Oslo and thinks she knows why.

Cholesterol mystery

But for Zinöcker the story began with another mystery: a question repeatedly posed by the nutrition students she teaches, and which she couldn’t answer.

That question was: “If you eat more saturated fat, the amount of LDL cholesterol in your blood increases. But we know that new cholesterol isn’t absorbed from food. Nor does it come from an increased production of cholesterol in the body. So where in the world is it coming from?”

And likewise, when you eat more polyunsaturated fat, the amount of LDL cholesterol in your blood decreases. But where does it go?

“I couldn’t explain it. Each time the question popped up, I tried to find research articles on the topic, but I couldn't find any answers,” Zinöcker says.

However, she refused to give up.

In search of something that could explain the issue, she dug deeper into the biology. What exactly is going on with cholesterol in our bodies?

The answers she found launched her onto a whole new track for understanding the cholesterol mystery.

Cholesterol in cell walls

"Most people think of cholesterol as something that is mainly found in the blood," says Zinöcker.

“But only a small part of it is found there. Most cholesterol is distributed throughout our cells.”

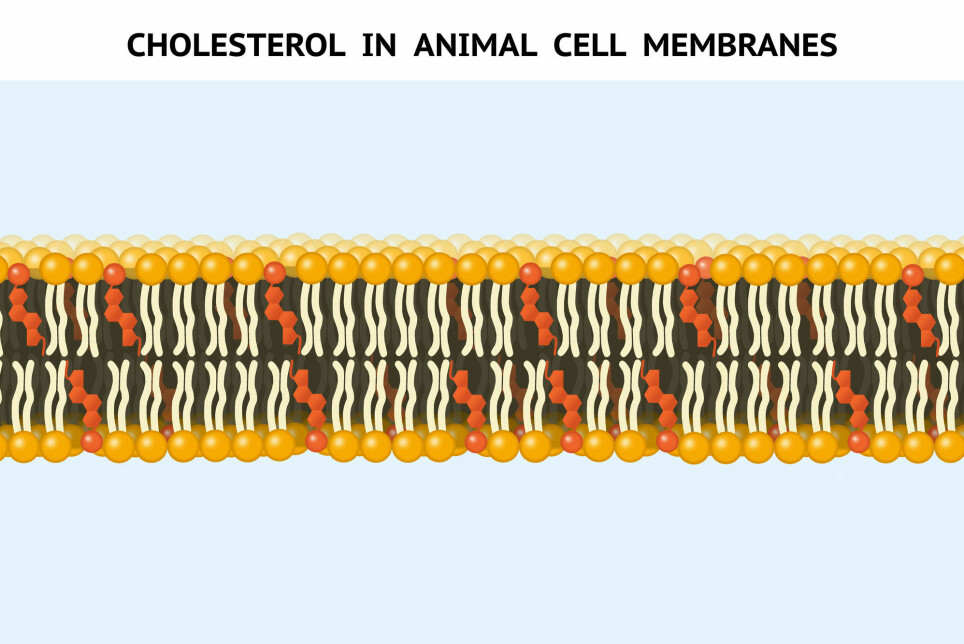

Cholesterol is an indispensable part of the cell membrane – a kind of flexible wall along the surface of the cells.

This membrane protects the cell contents inside, but it’s not completely impermeable. The cell needs substances like nutrients, building blocks and signalling substances from the rest of the body. It also has to get rid of waste.

The cell membrane allows substances in and out in a very controlled way. In fact, a well-functioning cell membrane is extremely important for the cell to function.

Research has shown that cholesterol is an essential component of this membrane. Between 30 and 50 percent of the cell membrane consists of cholesterol, where it has a very important task.

Adjusts membrane stiffness

"Cholesterol adjusts how fluid the membrane is," says Zinöcker.

The cell membrane can become more or less rigid, depending on how cold it is and what kinds of fats it consists of. The latter depends on what we eat.

When we eat more polyunsaturated fat, the cells incorporate more polyunsaturated fat into the cell membrane, making it more fluid. To compensate, the cell also incorporates more cholesterol in the membrane. Cholesterol has a stabilizing effect on the soft membrane.

If we eat more saturated fat, the opposite happens. The cell membrane becomes stiffer and no longer needs that much cholesterol.

Understanding this very basic mechanism is what put Zinöcker onto an answer to the students' questions and a completely new way of understanding the metabolism of cholesterol in the body.

Regulatory mechanism, not a sign of disease

Zinöcker thought, “When we eat more polyunsaturated fat, the cells collect cholesterol from the blood, and build it into the cell membranes to ensure that they become rigid enough. This is where the cholesterol has gone when we measure less cholesterol in the blood!”

And the opposite holds true as well – when we eat more saturated fat, the cell membranes become stiffer. The cells have less need to bring in stabilizing cholesterol and instead send it into the bloodstream. The cells also stop absorbing cholesterol, thus raising the blood cholesterol level.

In the second instance, Zinöcker arrived at another understanding:

The increase in blood cholesterol level as a result of more saturated fat in the diet may not be a sign of disease at all. On the contrary.

"The increased blood cholesterol level is probably a sign that the regulatory mechanisms in the body are working the way they should," says Zinöcker.

Perhaps the cholesterol in the blood of healthy people is simply a kind of emergency stockpile, which the body has at its disposal when the fluidity of the cell membranes needs to be adjusted.

“Cell stiffness is probably so important that the body doesn’t take a chance on covering the need exclusively through food,” says Zinöcker.

Two puzzles

But hold on.

The flow of cholesterol in and out of the membranes can explain how saturated fat leads to an increase in cholesterol in the blood, without this necessarily causing heart disease.

But what about the link between high cholesterol and heart disease? There is little doubt that people with high cholesterol have an increased risk of disease.

This piece of the puzzle still doesn’t fit.

Zinöcker thinks she has an answer to that too.

“The piece belongs to another puzzle,” she says.

“We’ve always believed that everything was part of the same picture. But I think there are two pictures. One is the image of a healthy body, and the other is of a body with a failure of the regulatory mechanisms.

Chronic inflammation

Most people with an increased risk of heart disease have a lot more than just their cholesterol levels out of balance. Their blood pressure and blood sugar are too high, the liver is too fatty and their insulin isn’t functioning properly.

And critically, measurements show signs of chronic inflammation in people with heart disease risk.

Several studies suggest that chronic inflammation in the body can disrupt many regulatory mechanisms in our cells.

Zinöcker believes chronic inflammation may be the root of the problems.

Could inflammation be leading to disturbances in regulating cholesterol and many other processes, which together increase the risk of heart disease?

In this scenario, it is conceivable that high cholesterol in people with chronic inflammation is only a signal of the regulatory disturbances and not a cause of heart disease per se.

Or maybe it plays a negative role, which it wouldn’t in a healthy body.

Zinöcker believes cholesterol levels in a healthy body mean something different from cholesterol levels in a sick body. When we mix the results of healthy and sick people, the measurements don’t make sense.

“To understand the connections, the two pictures must be kept separate,” she says.

Old knowledge, new model

The puzzle pieces thus began to fall into place for Zinöcker. She had built a foundation for a new model of the body’s cholesterol metabolism.

“None of this is new knowledge. It’s existing knowledge put together in a new way,” she says.

But could the idea really be correct? Might the professor actually have found a connection that no other researchers had discovered?

Zinöcker needed to investigate this.

She had the opportunity to present her model at a meeting at the University of Oslo, with researchers in the country's largest professional community in nutrition research.

Held water

Zinöcker wasn’t feeling so cocksure of herself.

“I was thinking, there must be something I haven’t understood that everyone else knows, and that makes the model flawed,” she says.

But amazingly, she encountered no such objections. The professionals at the meeting did not find any obvious impossibilities in the model.

One of the researchers, Karianne Svendsen, was interested in exploring the idea further. After a few months, Zinöcker, Svendsen and researcher Simon Dankel from the University of Bergen started collaborating to describe the new model.

Now they have presented the model in a recent article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

The HADL model

The researchers call it the HADL model.

They believe this way of understanding cholesterol metabolism in the body can also explain a fascinating feature of most cholesterol studies.

A Norwegian study from 2018 illustrates the phenomenon. Here a group of healthy students had eaten a diet high in saturated fat for three weeks.

Not unexpectedly, the blood cholesterol level in this group increased as compared to students on a regular diet. But the individual differences were staggering, from a barely noticeable increase in some to more than a doubling of cholesterol in others.

Why such a big difference?

Model explains huge differences

According to the new model, this individual variation can be explained based on what the participants ate in advance of the three-week diet.

If they had been consuming a lot of polyunsaturated fat and suddenly switched to a lot of saturated fat, the cell membranes would become much stiffer and the need for cholesterol much less. This person’s membranes would secrete a lot of cholesterol into the bloodstream.

On the other hand, the cell membranes in a participant who was eating a lot of saturated fat beforehand would already have gotten rid of a lot of cholesterol, resulting in only a slight cholesterol increase.

So a lot of pieces could fall into place if the researchers' idea is correct.

The researchers write in their article that if confirmed, the model could open up another approach to dietary advice to prevent cardiovascular disease, and perhaps also lead to dropping the use of the simplified terms "good HDL cholesterol" and "bad LDL cholesterol”.

The question is of course whether the model will be confirmed.

Currently based on theory

Kjetil Retterstøl, a professor at the University of Oslo, believes that a lot remains to be done before we can know if the idea has merit.

“The model's strength is that the phenomenon cannot be blatantly dismissed,” the professor tells forskning.no in an email.

The weakness, however, is that the model is currently based on theory, according to Retterstøl. No studies have yet tested whether the new model accurately reflects what happens with cholesterol.

Another weakness is the question of what happens over time. If you continue to eat saturated fat, then the cell membranes have already secreted the cholesterol molecules. What then? Why does the LDL remain high unless you are on a diet and losing weight?

Needs more research

Retterstøl thinks the model is exciting if it’s correct, but that we don’t yet know if the idea is true or what it might mean in practice. For starters, animal experiments need to be conducted that can determine whether the principles of the model are correct.

“The claim that the increase in LDL cholesterol is good and a sign of a healthy response is a premature interpretation. But should it turn out to be correct, then the authors have a big task if they want to prove that the high LDL cholesterol is beneficial,” says Retterstøl.

“I can hardly imagine high LDL being beneficial, because we know way too much about LDL's function for that,” he writes.

“It could be interesting if the HADL model turns out to bear fruit, but it doesn’t shake the fact we know – that saturated fat in the vast majority of people increases their LDL and that this in turn will increase their risk of cardiovascular disease,” Retterstøl says.

Translated by: Ingrid Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Reference:

M. K. Zinöcker, K. Svendsen, S. N. Dankel, The homeoviscous adaptation to dietary lipids (HADL) model explains controversies over saturated fat, cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease risk, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, January 2021. Abstract.