Planets are very different.

On this seemingly nice, blue planet, glass rains sideways.

This planet is hotter than some types of stars, and molecules are torn apart on the day side of the planet.

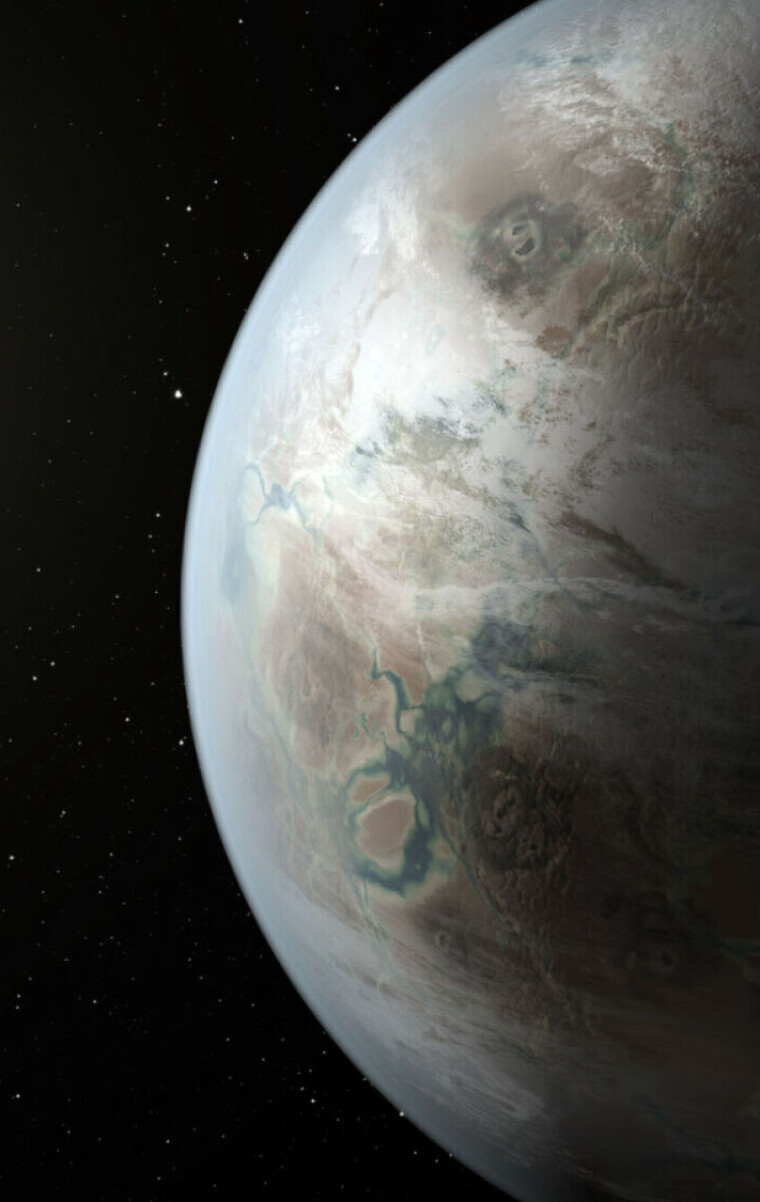

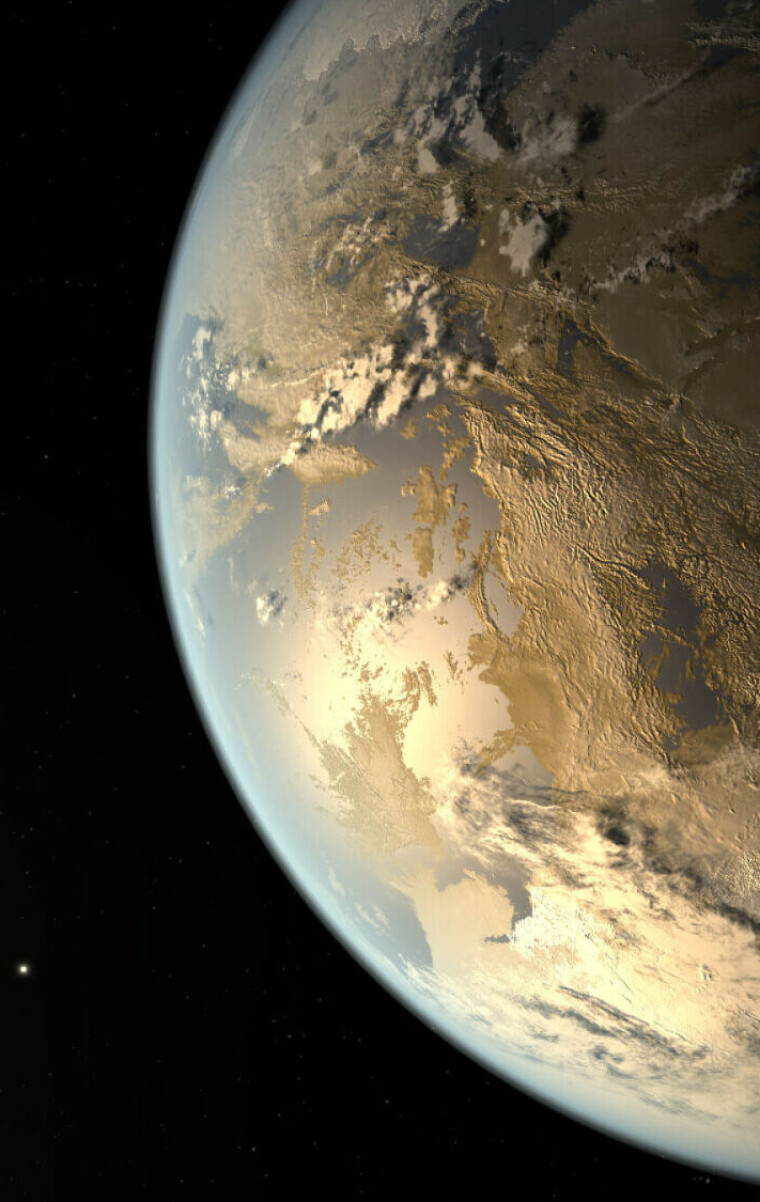

Kepler-452b has been called Earth 2.

It is slightly larger than Earth, orbits a similar sun, and takes about one year to complete a revolution.

The first alien planets were discovered in the 1990s. What have we learned?

Our solar system is far from a blueprint for what other solar systems look like.

The planets in our solar system are far from alone in the Milky Way.

There are 100 billion stars in our galaxy, and studies have shown that there are probably even more planets, according to NASA.

So far, over 5,700 planets have been discovered, with thousands of potential candidates still awaiting confirmation.

What kinds of planets are out there, and is our solar system typical?

Zombie system

“Research on exoplanets is a fairly young field in astronomy,” says Stephanie Werner, a professor at the University of Oslo and researcher at the Centre for Planetary Habitability.

The first planetary system discovered was nothing like our own. It was more like a zombie solar system.

Three planets were found orbiting a pulsar, a dead star.

Pulsars are extremely dense, spin at incredible speeds, and emit radiation from their poles.

These planets might have been formed from the remnants of their dead siblings – destroyed when the star exploded.

Appropriately named Draugr, Poltergeist, and Phobetor, these worlds were discovered in 1992 and 1994.

This marked the beginning of exoplanet research.

Giants in the wrong place

The following year, a planet was discovered orbiting an ordinary star.

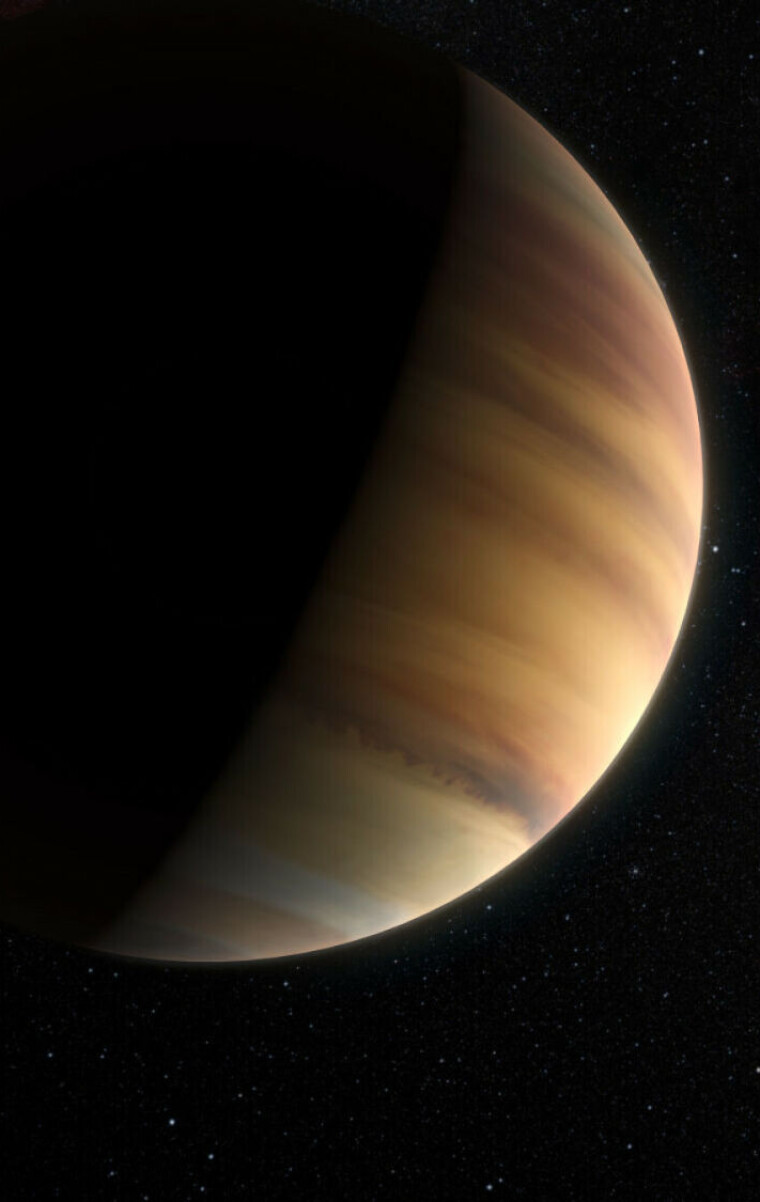

51 Pegasi b was far from a welcoming, new world.

In contrast to our solar system, where smaller rocky planets are arranged closer in and gas giants further out, 51 Pegasi b disrupted that neat order.

The planet orbits a star of the same type as our own sun.

But it is gigantic, larger than Jupiter, and moves extremely close to its star.

A year on this planet lasts only four days, and the temperature reaches 1,200 degrees Celsius.

These types of planets are called hot Jupiters: Jupiter-sized planets in close proximity to their stars. Several were discovered in the 1990s.

“Hot Jupiters strongly challenged the models we had for the development of the solar system,” says Werner.

Gas giants were believed to form far from their stars, so how did these planets end up so close?

“This discovery has led to changes in planet formation models,” she says.

Easiest to detect

At first, most of the planets discovered were these enormous, fast-orbiting worlds, completing their orbits in just a few days.

Fortunately, this is not all the Milky Way has to offer.

The reason so many of hot Jupiters were found was due to the method used in the hunt for these planets.

The radial velocity method relies on observing whether stars wobble slightly in their position.

The gravitational pull from a planet causes a star to wobble slightly.

Large planets close to a star cause more and faster wobbling, making them the easiest to detect.

In the 2000s, researchers began using a different method to find exoplanets.

New surprises were on the horizon.

A new type of planet

Researchers did not just find hot Jupiters, but also Jupiter-sized planets farther away and planets the size of Nepture or even smaller, explains Werner.

A new category of planets was discovered.

In size, they fall between Neptune and Earth.

Now, they are among the most commonly found planets, though they do not exist in our solar system, says Werner.

These new planets were called super-Earths or mini-Neptunes.

The method used to find them, the transit method, involves looking for a sudden dimming of a star's light. When a planet passes in front of its star, it blocks some of the light.

If this dimming happens repeatedly at the same intervals, there is most likely a planet there.

But what do super-Earths or mini-Neptunes look like? And are they even the same type of planet?

Some are compact, others not so much

They might be similar, but some could have developed larger atmospheres.

By combining the wobble and transit methods, researchers can determine the density of these planets.

Some appear to be compact and rocky, while others seem more gaseous and fuzzy.

"There's a lot of variety, and they're quite strange compared to what we know from the solar system,” says Werner.

Few of them seem to be oversized Earth-like planets.

“We're finding many more that are Neptune-like or slightly heavier,” she says.

Some are a mix between rocky and icy.

“One theory is that they have a significant amount of either water or gas, with a compressed atmosphere, and they aren’t entirely made of ice or gas. We don’t fully understand this in-between category yet. It’s probably something Earth-like at the core, with a strange atmosphere around it,” says Werner.

One theory suggests that some of these planets are made mostly of water, possibly even with global oceans.

Kepler-22b is a super-Earth and is described as a potential water world.

Another idea is that the smaller super-Earths were originally Neptune-type planets that drifted too close to their star.

Their atmospheres may have been scorched away, leaving behind only a mysterious rocky core.

Researchers have found very few hot Neptunes, meaning Neptune-like planets that are close to their star, according to NASA.

“This is one theory on how super-Earths formed, but we don't really know,” says Werner.

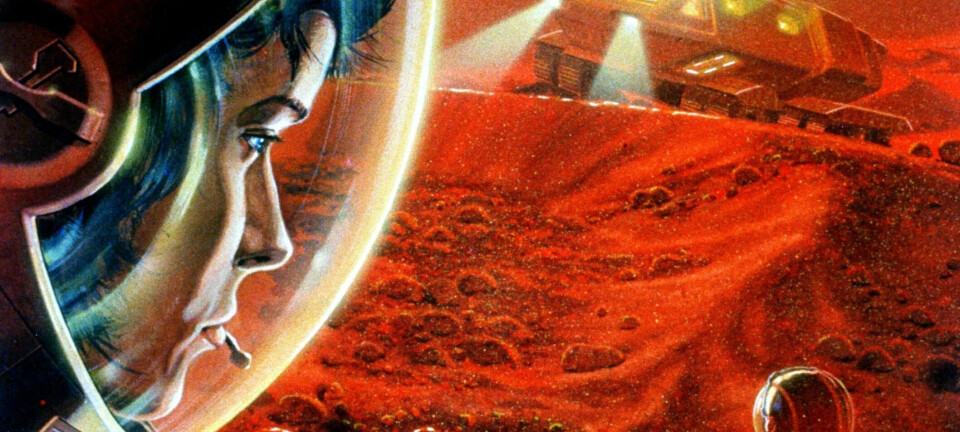

From Earth-like to utterly alien

Only about four per cent of the planets discovered are rocky planets. These are smaller planets the size of Earth, Mars, or Mercury.

We can only speculate what it looks like on them.

On Kepler-186f, it maight be warm enough for water to exist.

It is roughly the same size as Earth and takes 130 days to orbit its star.

Other planets look completely different from what we know.

In this cosmic jungle, there are planets with two suns. On Kepler-16b, there are two sunsets instead of one.

The hot Jupiter planet TrES-2b is known as the darkest of them all, reflecting less light than coal.

Researchers believe there could be super-Earths with hydrogen atmospheres and large, habitable oceans. These are called hycean planets.

Other research suggests there are planets with clouds of sand and some with diamond interiors.

Some planets have tidally locked rotations, always showing the same side to their star, while others drift freely through space without a star.

No longer surprised

As an exoplanet researcher, Stephanie Werner has learned to expect the unexpected.

“If you have our solar system in mind, almost every planet or planetary system looks different. It's more surprising to find something familiar than something new,” she says.

There is also great variation in how the planets are arranged in their system.

Many systems have been found where the planets, both large and small, are packed into tight orbits close to their star.

“Many of the systems we discover are crammed within Mercury's orbit and have these medium-sized planets that we don't have in our solar system. These systems look very different from ours and are, in that sense, quite exotic,” says Werner.

The star Kepler-223, for example, is larger than our sun and has four mini-Neptunes close by. The outermost planet takes only 20 days to complete one orbit.

There have also been some systems found with planets very far from their star.

In the system ROXs 42 B, a planet nine times as the mass of Jupiter has been found.

It takes nearly 2,000 years to orbit its star. By comparison, Jupiter takes 12 years to orbit the Sun.

Is our solar system typical?

Are planetary systems like ours common?

We don't know yet, says Werner. The way exoplanets are discovered makes it easier to find planets that orbit close to their star and those that are large.

To find planets with an orbit similar to Earth's using the transit method, the same star has to be observed for two to three years to capture two to three transits.

“With the new Plato mission, which will observe the sky for much longer than previous missions, we hope to find objects that are farther away. This means we'll discover more extended systems, up to Earth-like orbits,” says Werner.

Plato is set to launch in 2026. In theory, solar systems like ours should also be common, says Werner.

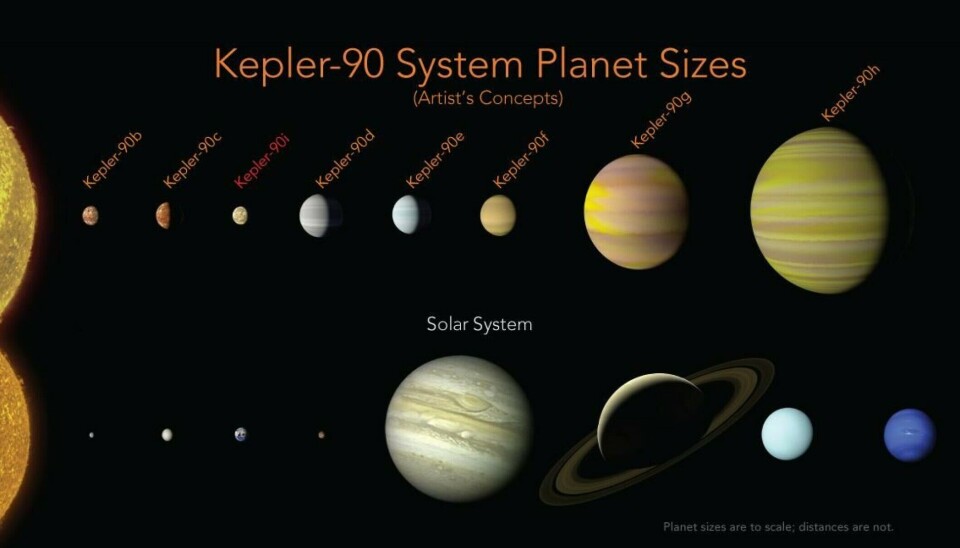

Kepler-90 is a planetary system with the same number of planets as our solar system.

The planets are arranged in a similar way, with several potentially rocky planets closer in and gas planets farther out.

However, the system is more compact than ours. The outermost gas planet takes about one year to orbit its star.

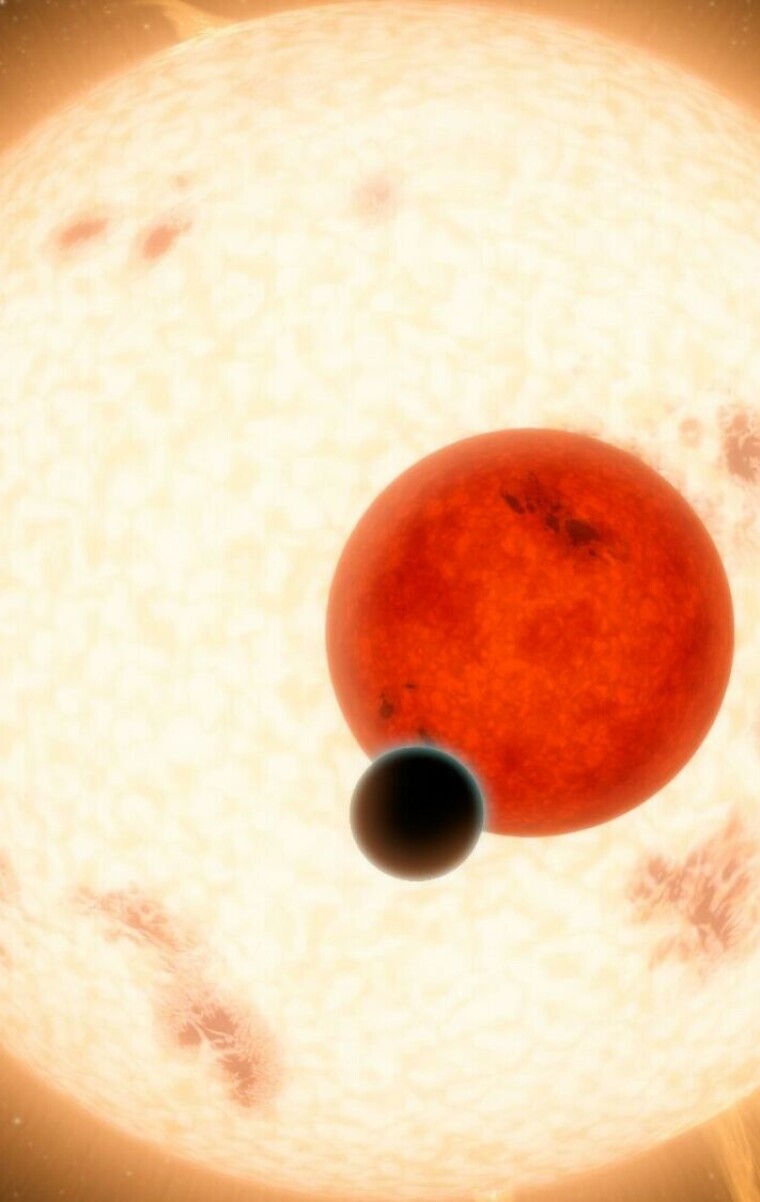

Most are smaller stars

The Sun is a fairly large and bright G-type star. This type of star makes up six per cent of the stars in the Milky Way.

Cooler and smaller stars are far more common: K-dwarfs make up 13 per cent, and M-type stars, or red dwarfs, accounr 73 per cent, according to Hubblesite.

Can life exist around the most common type of star in the Milky Way?

This is a hot topic, says Werner.

The habitable zone, where it could be warm enough for liquid water, is fairly close to a red dwarf star.

This means that planets in this zone are often tidally locked to the star, always showing the same side to the light, similar to how the Moon orbits Earth.

These planets would also be exposed to the intense activity of red dwarf stars. Red dwarfs seem to have frequent flares, especially when they are young, which can erode the atmospheres of planets.

“One of the major focuses in research is how a star's behaviour affects habitability,” says Werner.

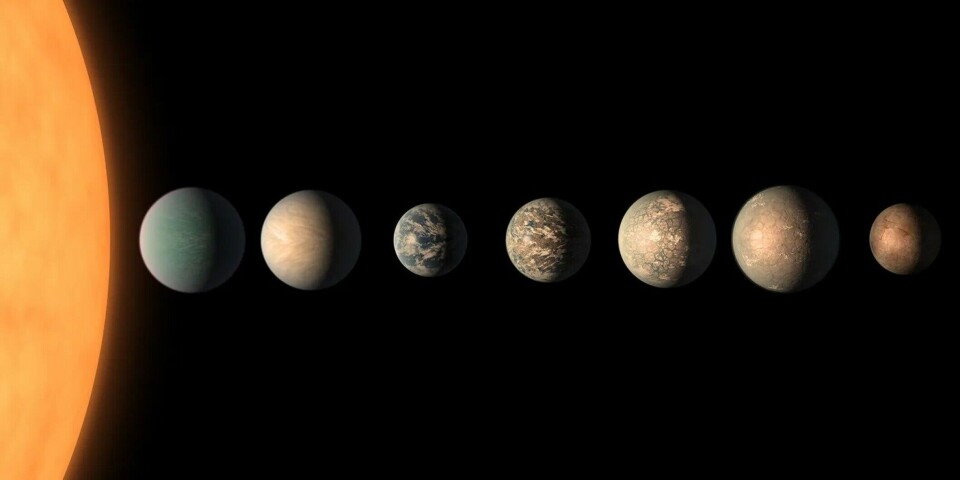

Trappist-1 is an intriguing planetary system for researchers, with a red dwarf star at its centre and seven rocky planets close to it.

“Several of these planets are within the habitable zone, but it doesn't look like they have the right atmosphere,” says Werner.

Our nearest star beyond the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is also a red dwarf with three planets.

The question remains whether any of the discovered planets have an atmosphere that could support life or even show signs of life.

Images:

HD 189733 b: NASA, ESA, M. Kornmesser

KELT-9b: NASA

Kepler-452b: NASA Ames / JPL-Caltech / T. Pyle

PSR B1257+12: NASA / JPL-Caltech

51 Pegasi b: ESO / M. Kornmesser / Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org)

Mini-Neptune: Pablo Carlos Budassi, CC BY-SA 4.0

Kepler-22b: NASA / Ames / JPL-Caltech

Kepler-186f: NASA Ames / SETI Institute / JPL-Caltech

Kepler-16b: NASA / JPL-Caltech

TrES-2b: JohnVanVliet / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

Hycean planet: Pablo Carlos Budassi / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no