This mass grave in Norway contained 19 men, each shot in the head and heart

“We shall die standing, boys!” Those were Arne Laudal’s last words just before the shots rang out.

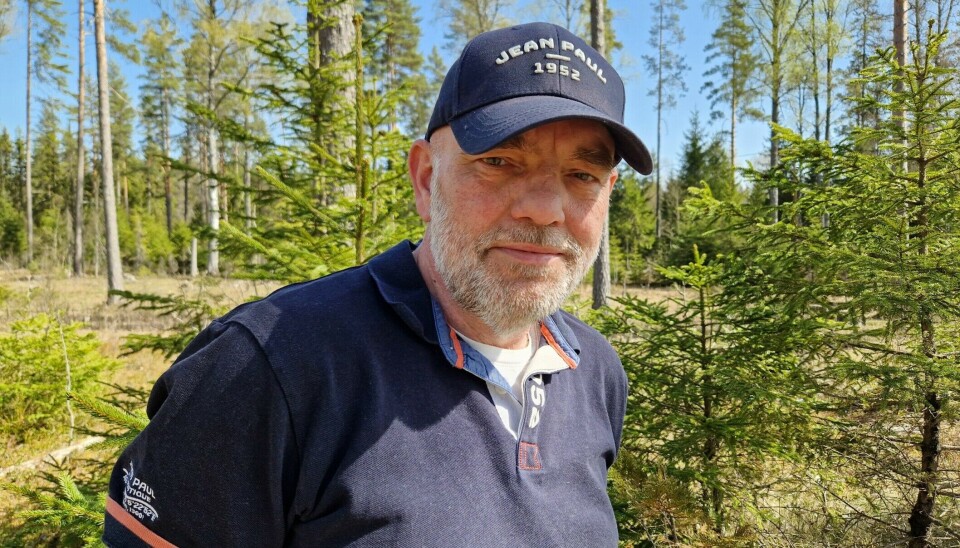

Petter Aunaas leads the way into the Trandum forest, about an hour's drive outside Oslo, Norway's capital. We pass one gravestone after another. Solid stone crosses are decorated with Norwegian flag ribbons and vases with withered and fresh flowers.

Aunaas stops at grave number 17.

“19 people were executed here on May 9, 1944. They were shot at the edge of the grave and either fell or were pushed in,” he says. Aunaas heads the Trandum Institute.

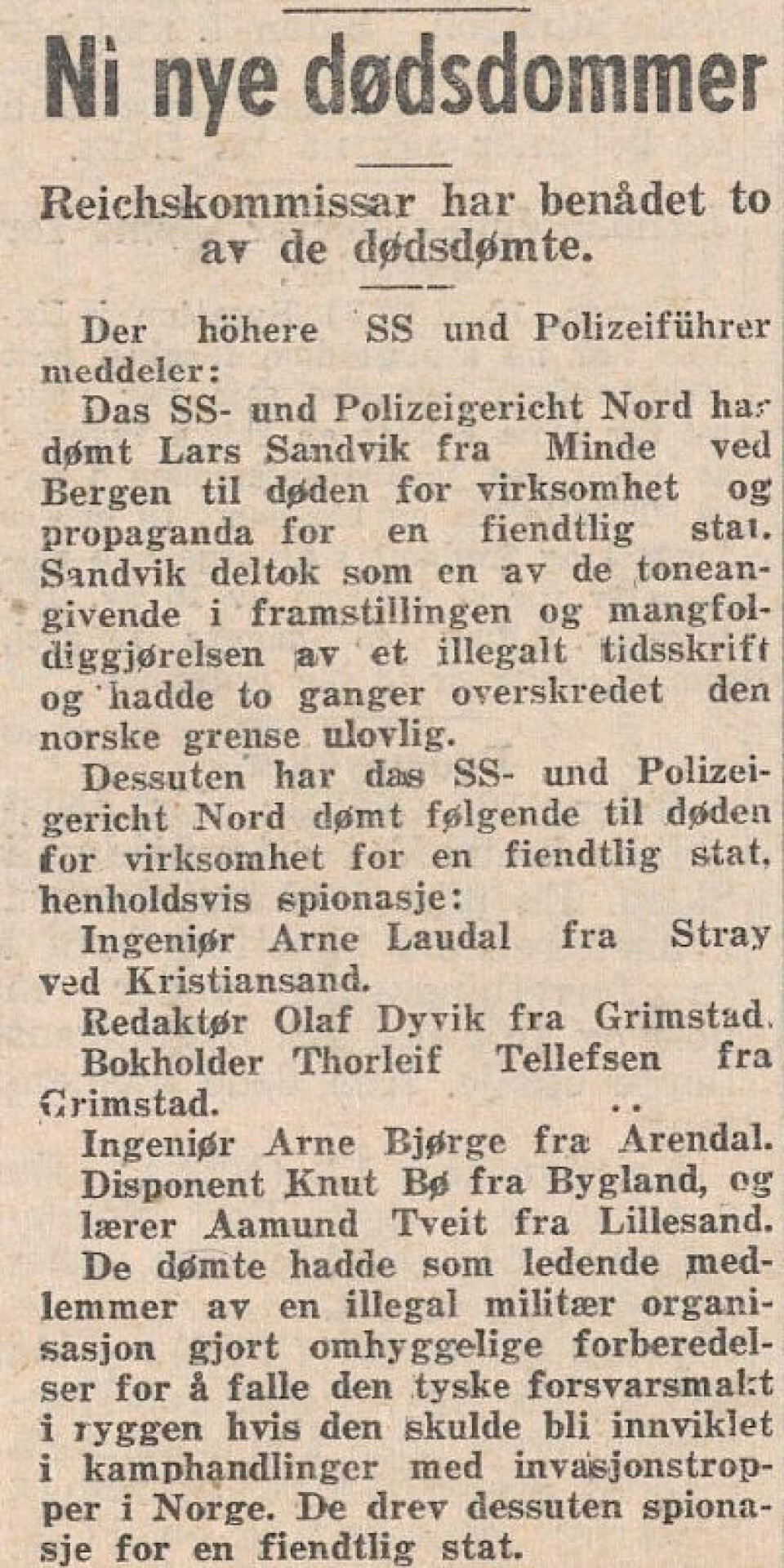

The German occupiers had exposed many members of the resistance groups in Kristiansand and Stavanger the previous autumn. Many of those arrested were sent to prison camps in Norway or concentration camps in Germany. However, those identified by the Nazis as leaders were sentenced to death or executed without trial.

“This was one of the largest mass graves in Trandum forest. The prisoners were taken at night, driven two hours by truck to the forest and the graves that were ready. Early in the morning, it was all over,” says Aunaas.

No one reacted to the sound of shots fired

Trandum military camp is the closest neighbour to Oslo Airport and is located just north of the runways.

When the Germans occupied Norway in 1940, they took over the camp. They expanded the airport and created a training grounds for tanks.

The forest right next to the shooting range became the place where the most Norwegians were executed during the war years. A total of 173 Norwegians, 15 Soviet prisoners of war, and six British soldiers were shot here.

“The Germans kept the execution site and the mass graves secret. There was a lot of shooting, bangs, and exercises going on here, so no one reacted to the sound of shots being fired,” says Aunaas.

Rolf was 24 years old, Leif almost 27

Leif Dahl joined the illegal resistance movement in Tønsberg after the occupation of Norway, according to the book Vestfold i krig (Vestfold at War). Weapons were in short supply, but help arrived by parachute in 1943.

Norwegian soldiers who were trained in England secretly provided training in weapons and explosives. The weapons arrived later, dropped in crates from planes.

Leif Dahl took part in the training and became a weapons instructor for others in Milorg, the name for the military resistance organisation in Norway.

Rolf Olaf Schulstad transported weapons around the area. In February 1944, he was stopped by German soldiers. They suspected that the license plates on the truck were fake.

Schulstad was arrested and subjected to harsh interrogations. Then Leif Dahl was arrested. He too was beaten by the Gestapo, the German police.

A couple of days after the arrest, death notices for Dahl and Schulstad appeared in the Tønsberg newspaper. 'Our beloved Leif has gone home to his Saviour,' it said, with the names of his parents and fiancée.

But the death notice was fake. The Gestapo wanted Milorg to believe that the two had taken their own lives and therefore had not revealed more names during interrogation.

Dahl and Schulstad lived for barely two more months.

Little chance in court

The two men were executed without trial. Others buried in grave number 17 had been sentenced in a German court under German law.

The trial of the group from Southern Norway took place a month before the execution. Their leader, Major Arne Laudal, forewarned the others that their chances of acquittal were minimal. The group agreed to act like true men and not be intimidated, according to the book Frihetens flamme (The flame of Freedom).

A German defence attorney was appointed for the group. None of the defendants had spoken with him, and they didn't even know his name. The trial was conducted in German, with an interpreter for the prisoners. The judges took half an hour to issue eight death sentences.

One of the defendants was a doctor. He was charged with treating a wounded paratrooper without reporting him to the police. He was sentenced to eight years in prison and survived the war.

The sentences could not be appealed, but it was possible to apply for a pardon. This rarely happened, but the two youngest in the group had their death sentence commuted to rehabilitation at Grini prison camp. Both survived the war.

The other six were executed and ended up in grave 17 in Trandum forest.

Ferdinand was 25 years old

Despite his young age, Ferdinand Tjemsland became the leader of the communist resistance group in Stavanger. They published the illegal newspapers Stritt Folk (Resilient people) and Friheten (Freedom), operated a radio, carried out sabotage, and helped people flee, according to the book En fortiet historie (A Silenced Story).

In August 1943, Tjemsland was on his way to Stavanger with a new batch of illegal newspapers. A Norwegian Nazi is also onboard the ferry. He reported Tjemsland to the German police, who were ready for him when the ferry docked.

Tjemsland had his dog with him. He ran through narrow streets to shake off his pursuers and found a hiding place. But the dog revealed his location.

Tjemsland's resistance group was dismantled, and many were arrested. Nine of them were sentenced to death.

One member wrote about the trial in a letter that was smuggled out of Grini, recounted in the book En fortiet historie: 'It was a cruel comedy that had nothing to do with justice. It was pure terror. Fortunately, the Germans did not get the satisfaction of seeing any of us break down. All nine accepted their sentences with heads held high.'

Taken at night by truck

Hauptsturmführer Oskar Hans led the unit in the German Security Police responsible for executions.

The Sonderkommando consisted of about 30 people.

“Germans who had military training were selected, even though most of them had office jobs at Viktoria Terrasse,” says Aunaas.

Viktoria Terasse was the headquarters of the SS and Gestapo.

The executions were secret and efficient.

“Oskar Hans was notified of the executions the day before. A group from the Sonderkommando picked up the prisoners at Grini, Akershus, or the prison in Møllergata. They were bound together in pairs and placed in a truck well hidden behind tarpaulins,” says Aunaas.

At that point the prisoners were informed that they were to be executed, but not told where.

Others in the Sonderkommando had dug a large pit in the ground in Trandum forest.

Shot in successive rounds

It took a couple of hours to drive to Trandum, the last stretch on poor forest roads. If there was snow, the prisoners had to walk the rest of the way themselves.

A short distance from the pits that had been dug, the prisoners were again read their death sentences. They were then lined up along the edge of the pit, bound together with wire and blindfolded.

“Three soldiers shot at each prisoner, two shots to the head and one to the heart,” says Aunaas.

On this night, May 9, 1944, there were 19 prisoners to be executed.

“They didn't have the capacity to shoot them all at once. Twelve soldiers shot four at a time, while the others waited,” he says.

This was explained by Oskar Hans during interrogations after the war. Hans and others in the Sonderkommando also said that the dead were laid neatly in the grave.

"That doesn’t match what was found when the graves were opened. People were lying every which way, where they’d fallen or been thrown in,” says Aunaas.

At six o'clock in the morning, the grave was covered, and the executioners had left.

The following day, the death sentences were published in all newspapers, as well as that they had been carried out.

“The Nazis wanted to create uncertainty among the population. The families were informed about the execution, but not where or when it happened, or where they were buried,” says Aunaas.

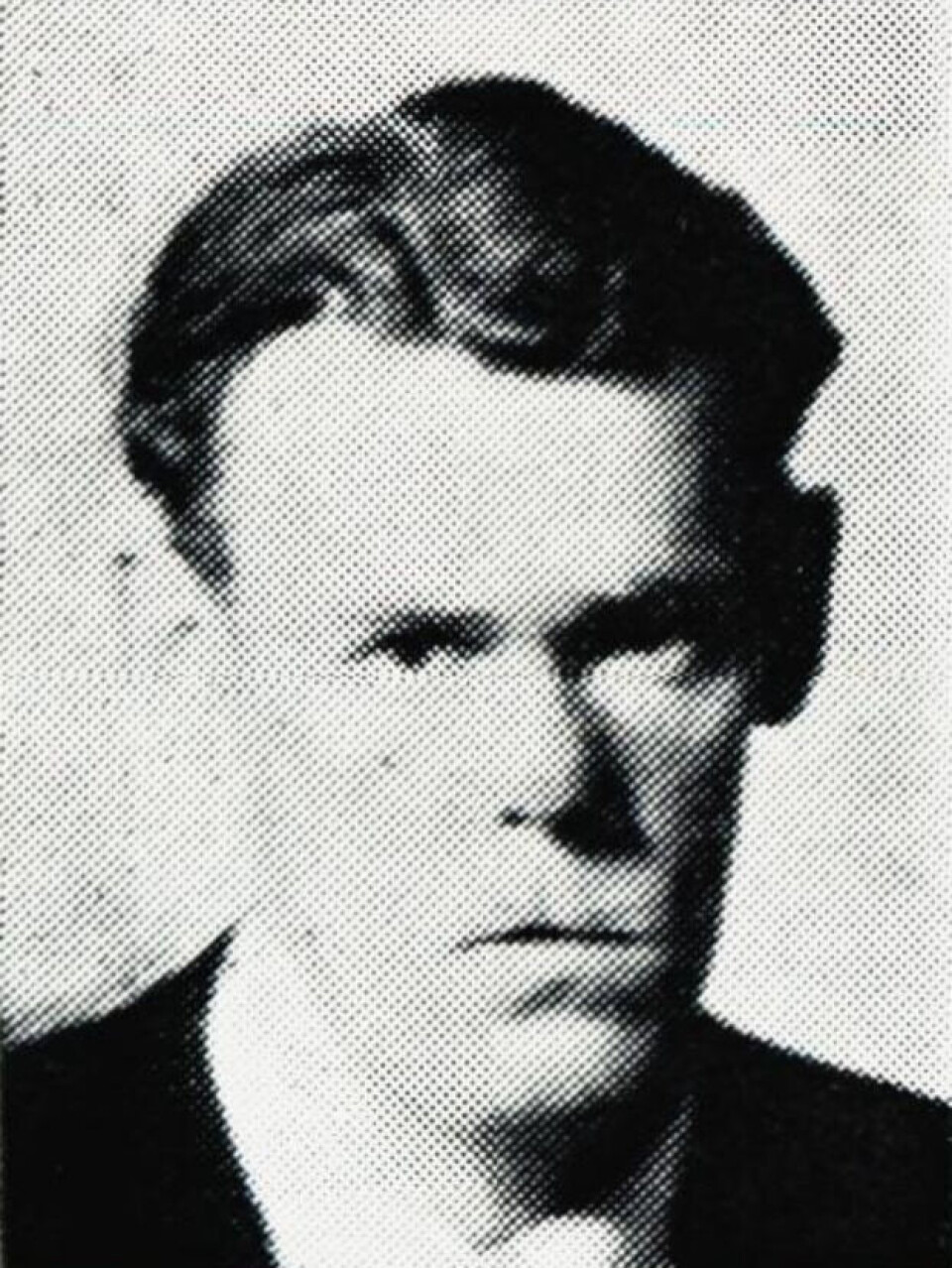

Arne Laudal was 51 years old

Arne Laudal is the most well-known of those shot that night. His story is often included in books about World War II in Norway.

Laudal was a major in the army and fought against the Germans in the spring of 1940. When Norway capitulated in June, Laudal began building and leading the resistance in the south of Norway, according to the book Frihetens flamme, (The Flame of Freedon). More than 3,500 members of his organisation were ready to support the British invasion that was expected in 1942. It never came.

Then everything unravelled. Laudal and many other resistance members were arrested by the German Security Police.

Prisoners at Grini who survived the war reported that Laudal maintained morale and discipline among the men condemned to death. It took a year and a half from the time the Laudal group was arrested until they were shot.

In a letter to his former boss, General Ruge, Laudal wrote: 'I will try to conduct myself as a worthy representative to the end.'

According to one of his fellow prisoners, Laudal told his men as they were led to the truck: ‘For Norway, our dear fatherland, no sacrifice is too great. Thus, it is not even too burdensome to lose our lives,’ as recounted in Frihetens flamme.

At the edge of the grave, before the shots, Laudalshouted: ‘We shall die standing, boys!’ This was confirmed by members of the Sonderkommando during post-war interrogations, according to Aunaas.

After the war, the story spread that Laudal also refused to wear a blindfold. The Germans had apparently agreed to that.

But that did not happen.

“The report from the forensic institute states that he was found blindfolded,” says Aunaas.

Pointed out the mass graves

On May 8, 1945, Norway was once again a free country. Many people were missing.

Those who did not return were sought through newspapers and radio. Ferdinand Tjemsland was one of them.

It was known that many prisoners had been executed, but not where. However, rumours had circulated for a while about what was going on in Trandum forest.

In June, the first mass grave was found. Then several more.

Oskar Hans was captured. He had put on a soldier's uniform and tried to escape among the crowd of ordinary German soldiers.

During interrogations, he described the executions, regulations, and procedures. He was taken out into the forest and pointed out the places where people were shot and buried.

A total of 18 mass graves containing 194 bodies were exhumed in the summer of 1945, under extensive media coverage.

German and Norwegian Nazis were brought out of prisons to do the digging.

“Some were German, but most were interned Norwegian Nazis. They hadn't been convicted of anything but were used in the graves to retrieve the decaying bodies,” says Aunaas.

The bodies were sent to the Forensic Institute in Oslo to be identified.

Communists with no shoes

“Every day, lorries full of bodies arrived, but the Forensic Institute didn’t have large enough cooling rooms or the capacity to store bodies in such poor condition. They solved the problem by noting characteristics and what they were wearing. The jaws with teeth were preserved, while the bodies were cremated,” says Aunaas.

Some of the deceased had rings and watches. One was carrying a letter from his wife, telling him they were expecting a child.

Families with missing loved ones submitted dental records and documentation from dentists.

“They managed to identify everyone, with the exception of one Soviet prisoner,” says Aunaas.

The dead were in civilian clothes. Ferdinand Tjemsland's group stood out.

“He and the other communists weren’t wearing shoes. It could've been an additional humiliation that they had to die barefoot,” he says.

It is also possible that they gave them to fellow prisoners. After the war, a fellow prisoner reported that Tjemsland and the others gave away their shoes and clothes before they were taken to the truck, according to the book En fortiet historie.

The urns were sent to the families. Funerals with honours, wreaths, and speeches took place throughout the summer and autumn.

What happened to the executioners?

More than 60 Germans were part of the Sonderkommando during the war.

Many of them tried to flee in May of 1945.

“They obtained false papers and military uniforms and hid among the soldiers. The British, in particular, devoted significant resources to identifying the war criminals, and they found a lot of them,” says Aunaas.

Oskar Hans was charged with the execution of 312 Norwegians. In his trial in 1947, Hans admitted to 215 of them.

At least 68 resistance members were shot without trial. For these, Hans was sentenced to death.

Most viewed

But the Norwegian Supreme Court overruled the conviction. Hans was expelled from Norway, only to be arrested by the British. The British court sentenced Hans to death for the execution of six British prisoners.

Again, the sentence was overturned. Hans was sentenced to 15 years in prison, and was released in 1954.

40 members of the Sonderkommando were arrested, sentenced, and imprisoned in Norway. About 20 of them disappeared without a trace, according to Aunaas.

“In questionings and trials, they admitted to having participated in executions, but all claimed they were following orders. They said they would have been shot if they had refused. None of them received the death penalty for the executions,” he says.

Aunaas himself has a background in the Norwegian Intelligence Service, which has come in handy in his work to document the history of the 194 individuals found in the graves.

The Trandum Foundation and the Trandum Institute are working to convey the events in Trandum forest and to establish Trandum Camp as a military museum and cultural history centre.

Most of the work is done by volunteers, many of them veterans from the Norwegian army.

References:

The newspaper archive (link in Norwegian), National Library of Norway.

Nøkleby, B. Skutt blir den - Tysk bruk av dødsstraff i Norge 1940-1945 (Shot they will be - German use of the death penalty in Norway 1940-1945), Gyldendal, 1996.

Christophersen, E. Vestfold i krig (Vestfold at War), Bokkomiteen, 1989.

Arntsen, J.M. En fortiet historie (A Silenced Story), Piren publishing house, 2018.

Taraldsen, K. Frihetens flamme (The Flame of Freedom), Fædrelandsvennen, 1994.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no