The unknown story of the liberation of Norway:

The Germans first surrendered to a group of journalists

A motley assembly of war correspondents and photographers tricked the German commander and were welcomed as heroes in Norway's capital Oslo.

Much has been written about the liberation of Norway and the German capitulation on 8 May 1945.

A lesser-known story, which has mostly been overlooked in the history books, is about a group of journalists' spontaneous trip to Oslo the day before.

At the airport, these journalists convinced the German commander to surrender. They then travelled to Oslo and were greeted by a cheering crowd.

But the story has largely been forgotten in the years that have passed.

Only Norway remained

In the first days of May 1945, country after country was liberated. Hitler was dead, Germany was defeated.

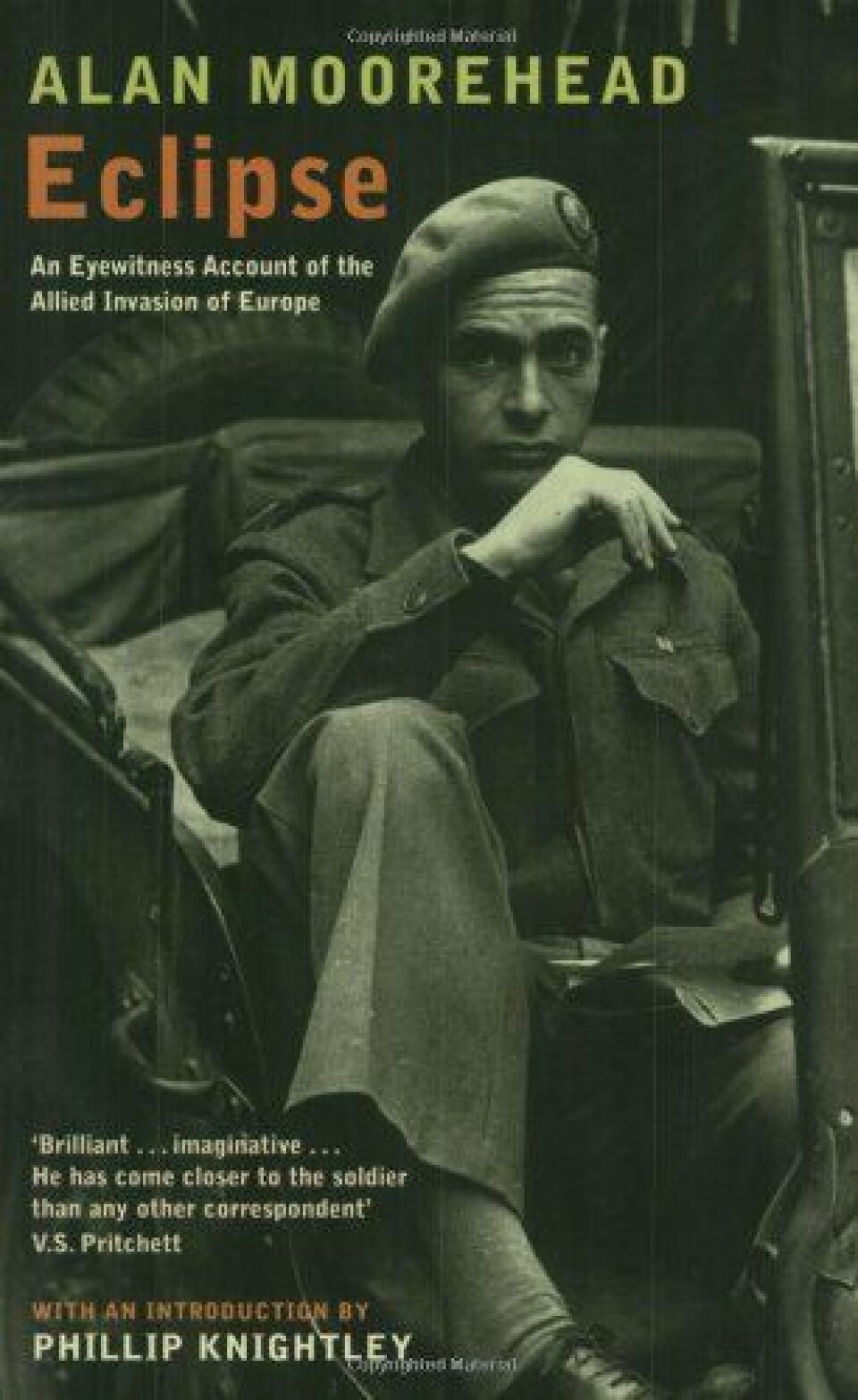

Famous war correspondents Alan Moorehead and Alexander Clifton had covered World War II from beginning to end. They had accompanied the Allied forces in battle, defeat, and to final victory.

On 7 May 1945, the two Britons had breakfast at a hotel in Copenhagen. They had reported on the liberation of Denmark just two days previously.

At the breakfast table, they realised that only Norway remained to be freed. But no one they talked to in Copenhagen knew anything about the plans for the liberation of Norway. Moorehead recounts this in his book Eclipse.

Awaited commission from London

On this day, everyone in Norway was certain that peace was inevitable, and had cautiously started to celebrate, but the Germans had still not capitulated. They were supposed to surrender to an Allied military commission comprised of British and Norwegian officers, which was on its way from London.

The Norwegian government in London had authorised the Home Front to act on their behalf. 40,000 men and women were in the process of reclaiming Norway, but there were still 350,000 German soldiers in the country.

In Copenhagen, the two journalists decided they wanted to experience the liberation of Norway first-hand.

They encountered two British pilots with access to aircraft, who liked the plan. The Danish journalist Ebbe Munck and some photographers also decided to join them.

Would the Germans shoot them down?

In his book, Moorehead describes how they took off in brilliant sunshine. They had found a map of Norway and the flight route in a Russian plane.

But the trip was poorly planned. Only when they were in the air did they begin to consider the situation they would face. Had the Allied forces arrived? Had the Germans capitulated? If not, would they shoot at their plane? Would the Germans let the plane land? Would they themselves be arrested?

'It was the worst possible place and time to debate the matter,' Moorehead wrote, because they could now see the coast of Norway.

'Two Swedish soldiers who were travelling with us — I do not quite know why, except they seemed to fit in with the general craziness of the whole operation,' Moorehead wrote.

Found the airport on the third attempt

They looked out the window. They saw no Norwegian flags flying, but there was also no anti-aircraft fire.

As they flew over Oslo, they saw that people were out in the streets. After three circles over the city, they found the airport. It was full of German planes.

'They flashed a red light warning to us not to land, but the pilot decided to go ahead anyway,' Moorehead wrote.

The Germans stared at them as they got out of the plane. The pilots were in blue uniforms, the two Swedes in green, while the journalists were dressed in khaki.

While waiting for the commander of the airfield, three enthusiastic British pilots approached them. They had escaped from a prison-of-war camp that same morning.

Would not shake hands with the Nazi

Eventually, a German colonel and several officers approached the group of journalists and aircrew. They gave the Nazi salute, and the colonel tried to shake hands with the two pilots in uniform.

But they refused to shake his hand. The colonel nevertheless started negotiations in formal terms. Alexander Clifford knew German and took over. He demanded that the Germans surrender to them, Moorehead wrote.

The colonel objected, saying he had been told that a commission from London would arrive on an entirely different plane and that the capitulation would occur at midnight.

Moorehead wrote that Clifford insisted that the Germans must surrender now and asked the colonel to contact the German High Command.

Capitulation at Fornebu

The colonel was still hesitant and resented that the photographers were shouting instructions. Clifford threatened to call the High Command himself. Then the German surrendered, and Fornebu was suddenly in British, Danish, and Swedish hands.

Clifford then asked for three cars. One quickly broke down, but Clifford stopped a car with two German officers and demanded they drive them into the city.

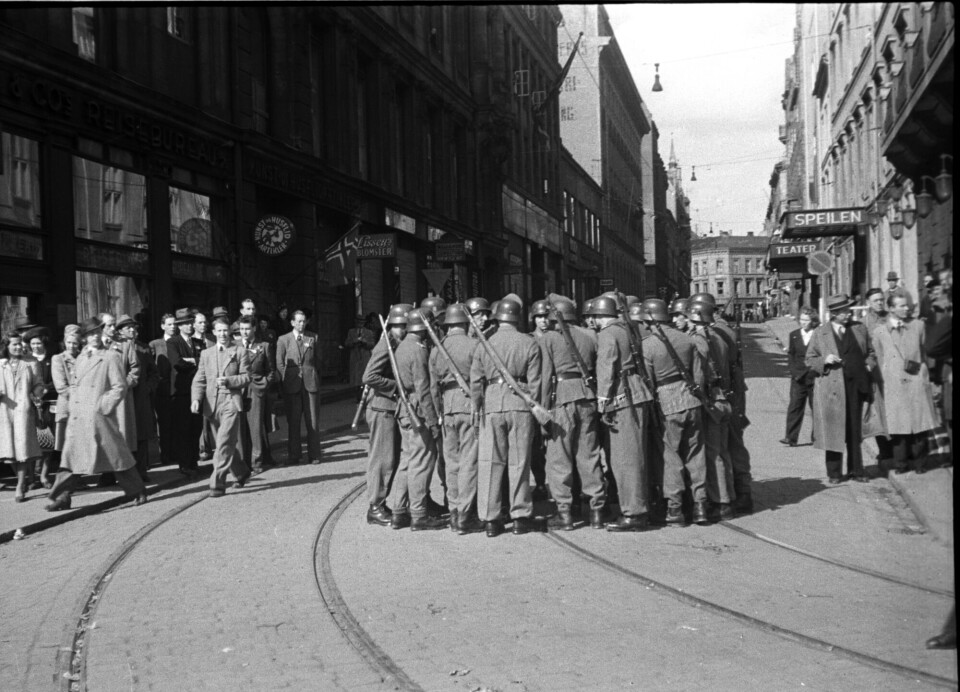

When people in the streets spotted the cars with people in non-German uniforms, they came running.

'The overall expression was clear enough: spontaneous, explosive, full of contagious colour and noise,' Moorehead wrote.

The crowd quickly became difficult to control. German soldiers held people back from the cars.

'Then some of the Resistance lads pushed through to help, and linking arms with their bitter enemies the Germans, tey cleared a few more yards along the street,' Moorehead wrote.

Hi-yah

They stopped at the Grand Hotel, where they were showered with flags and flowers.

'Norwegians have their own special cry of exaltation. This one sounds like "Hi-yah",' Moorehead wrote.

At the Grand, they were pushed out onto the balcony facing Karl Johans gate. A sea of people cheered and waved flags. Then they sang the national anthem.

'The men standing stiffly, the women in tears,' Moorehead recalled.

One of the pilots gave a speech to the crowd outside. Then everyone gave speeches. The national anthem was sung again, while German soldiers stood around in the crowd.

People poured into the suite at the Grand Hotel, bearing flowers and champagne. A drunk man gave his own speech from the balcony. Two members of the Home Front appeared, straight from a prison camp.

Responsible parties took action

The situation developed quickly, and Moorehead thought they should find some representatives of the authorities who could take control of the city from the Germans.

Outside, people continued to cheer and shout their strange hi-yah hi-yah. The noise only subsided when we gave speeches, Moorehead wrote.

Most viewed

A delegation of responsible individuals appeared and informed them that the Allied Commission was on its way to receive the German capitulation.

'The chief of police volunteered an escort to get us back to the aerodrome. One of the air commodores shouted one last word to the people: "We have all admired the spirit of your resistance",' Moorehead wrote.

A long day

They returned to Fornebu airport. The colonel had disappeared. The three British pilots were still there and jumped aboard.

'Norway was out of the war. We were flying on to a Europe and to England where there was only peace. So many liberations. So much tragedy between them. [We] settled back in the plane and fell asleep. It had been a long day,' Moorehead wrote.

The next day, Moorehead wrote about the event in the newspaper he worked for, the Daily Express in London.

In Norway, the journalists' takeover of Fornebu and triumph over Karl Johan is hardly mentioned. Only Dagbladet and Moss Avis covered the event. The Danish journalist, Ebbe Munck, noted that they were surprised their plane arrived before the Allied Military Commission. They were even more surprised that the commander at Fornebu thought they were the commission and surrendered the airport to them.

Furious chief of police

The story might have been considered too frivolous during these important days. There was also so much else happening that was deemed more important. There was also a shortage of newsprint.

Historians who have written about the liberation of Norway also do not mention that Fornebu was handed over to civilians and pilots on a spontaneous trip, except for the journalist Alf R. Jacobsen in his book 1945.

He wrote that the police chief was furious about the incident and that the British were chased out of Oslo. He did not want Liberation Day to end in a farce.

Historian Ole Kristian Grimnes found no room for spontaneous initiatives in his extensive work on Norway in World War II.

An orderly process

The liberation is depicted as an orderly and calm process. The Germans capitulated unconditionally on the night between May 8 and 9. Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling was arrested along with other leading Norwegian Nazis. The German Reich Commissioner Josef Terboven took his own life, other German officers were arrested, and German soldiers were continuously sent out of the country.

The government in London and the Home Front leadership in Oslo had planned the transition from war to peace very thoroughly, Grimnes wrote.

In his version, Moorehead's narrative fits poorly.

Last, brilliant experience

Moorehead's book Eclipse was published in the autumn of 1945. It was reviewed in several Norwegian newspapers. Even there, his trip to Norway is only mentioned in passing.

The end of the book 'shows the final stages of Germany's collapse, the capitulation, the horrors of the concentration camps, and the contrasting effect when the author immediately afterwards experiences the liberation of Denmark and Norway,' reads Aftenposten's review on December 10, 1946.

The newspaper Vårt Land also has a full review of the book: ‘Denmark and Norway in the euphoria of freedom become the author's final brilliant experience,’ it reads.

References:

Grimnes, O.K. 'Norge under andre verdenskrig, 1939-1945' (Norway during the Second World War, 1939-1945), Aschehoug, 2018. ISBN: 9788203297526

Jacobsen, A.R. '1945 - Hat, hevn, håp' (Hate, revenge, hope), Vega publishing house, 2016. ISBN: 9788282114196

Moorehead, A. 'Eclipse', Penguin Books, 1945 / 2022. ISBN: 9780552179126

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no