The judge who saved witches from the stake

A boat sank in nice weather. A cow died suddenly. Two neighbours quarrelled. A woman made a strength drink to earn a little extra. These were incidents that could become dangerous for women in the 17th century.

People in the 17th century believed in both witchcraft and God. So did the king, the priests, the judges, and others in positions of power in towns and villages.

330 people were executed as witches in Norway between 1570 and 1695. Most were women. As many as 1,000 others were imprisoned, fined, or exiled.

The witch-hunts were worst in Finnmark county, in the north of Norway, where 92 people were killed. Two died from torture, a few were beheaded, the rest were burned.

Kari Olsdatter

In 1621, Kari Olsdatter was accused of being a witch. The trial went quickly, because Kari confessed. She said she worked for the Devil, she could transform into a raven, and that she had flown to a witch gathering. Admittedly, the alleged witch had harmed neither animals nor humans, but her confession was proof enough.

Kari was burned at the stake in 1621.

25 years later, Mandrup Pedersen Schønnebøl got a job as a judge.

“The Norwegian legal system in the 17th century was almost like to today. Cases were heard in the district court first, then the parties could appeal to the court of appeal and the Supreme Court,” says Rune Blix Hagen, a researcher at UiT the Arctic University of Norway.

However, one big difference was that the court of appeal consisted of one man. For Nordland and Finnmark counties, that man was Schønnebøl. He was the son of a judge, born and raised in Norway, but of Danish nobility.

“As a court of appeal judge, he was responsible for the entire region. According to his job description, he was supposed to go to Finnmark every three years,” says Hagen.

There, Schønnebøl travelled between 15 different fishing villages and judged cases involving taxes, theft, and violence.

Then he ended up in the middle of the witch trials.

10 witches in Vardø

The persecution of witches occurred in waves. In 1662, many women in Eastern Finnmark were accused.

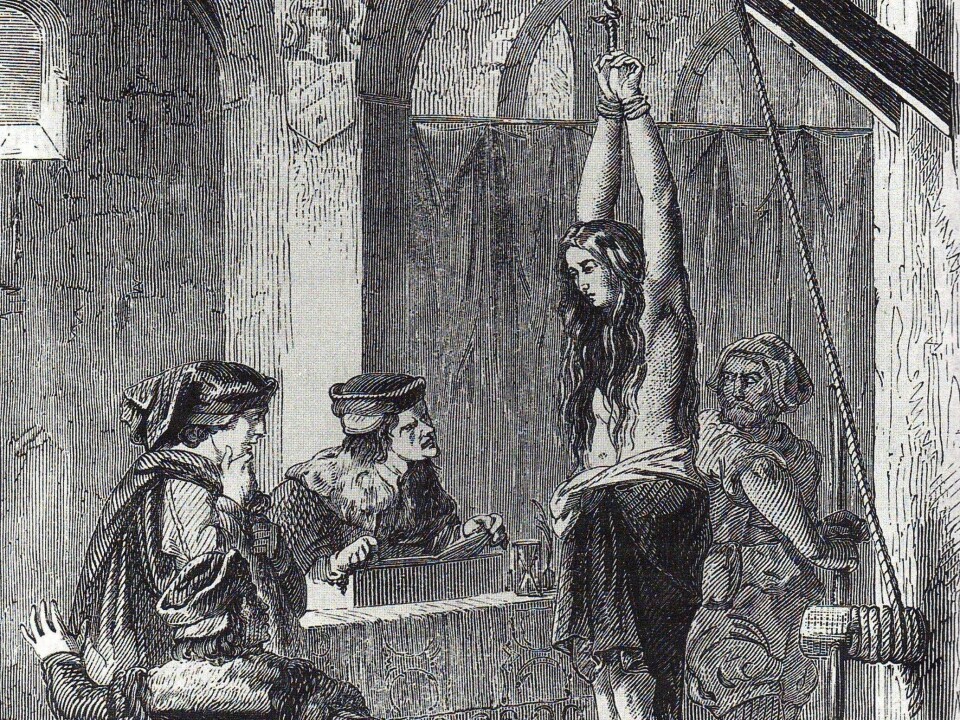

They were arrested and tortured. They were hung up, had their arms and legs dislocated on a torture rack, and were burned with red-hot tongs. They were threatened with eternal damnation and hell.

The torture continued until the women confessed. Then they spoke of meetings with the Devil, about witchcraft, and witch' parties – everything the torturers expected to hear. The women took the blame for poor crops, diseases, and deaths. The violence did not end until the victim gave the names of other supposed witches.

This is how a single arrest would lead to several more.

The daughters of the accused witches were also arrested: like mother, like daughter.

Within six months, 20 women were burned at the stake. 10 were imprisoned. Their cases had been appealed to the court of appeals, which was on its way to Finnmark.

Four of the ten were adults. Their death sentences were postponed because they were pregnant. Six were children. The youngest was eight-year-old Karen Iversdatter. Her mother had been convicted and burned as a witch.

When judge Schønnebøl arrived in June, he did something few judges had done before him. He followed the law to the letter, benefitting the children and women in the dungeon.

Punishment without mercy

Christan IV was king of Denmark-Norway. He believed in witches and witchcraft, as did many others at the time. After a trip to Norway, he specifically warned against witches in the north and the Sámi's use of magic.

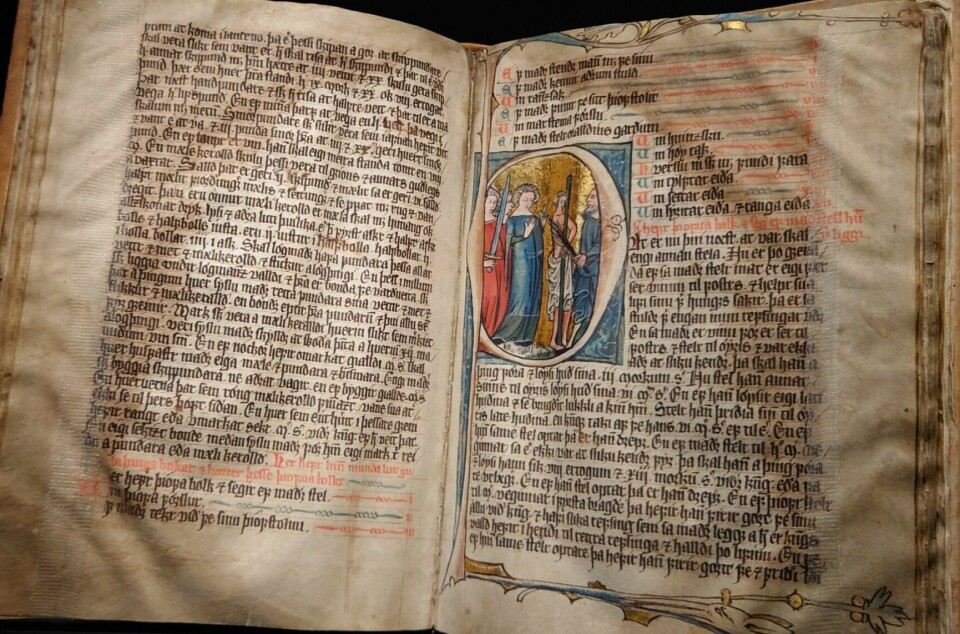

Christian IV introduced the first law on witchcraft in 1617. Bishops, priests, district court judges, and all others in public positions were required to find, prosecute, and punish witches.

They were to be ‘punished without mercy,' meaning the death penalty.

“Witchcraft was considered a very serious crime and was to be judged with the most severe punishment they had, which was to burn the sinful body at the stake,” says Hagen.

The king was in agreement with the spirit of the times. All over Europe, the church, kings, and their men believed that the Devil was actively trying to create chaos and destroy God and society. Women in particular were thought to be easily influenced by the Devil. There was a broad agreement that to be burned at the stake was the right punishment. Even Martin Luther supported the burning of witches.

It seems that Mandrup Pedersen Schønnebøl also believed in witchcraft, at least initially. He sentenced two women to death in 1656. They had confessed to killing three men using witchcraft.

However, Schønnebøl had also acquitted many accused. The 10 women sitting in the dungeon in Vardø thus had a chance of living.

Followed the law strictly

“Schønnebøl used the law the way it was intended,” says Hagen.

He dismissed witnesses who had been convicted of crimes, as stated in the law.

“One of the reasons there were so many witch trials in Finnmark is that the accused, under physical and psychological torture, were forced to provide the names of other witches," he says.

These names could not be presented in Schønnebøl's trials, because the individuals providing them had been convicted of witchcraft.

“Thus, the whole basis for the trials collapsed,” says Hagen.

Schønnebøl also introduced character witnesses. Family and neighbours of the accused woman were allowed to testify in court that they had not seen any witchcraft and that she was a good person.

He flatly rejected the water test, which was applied to determine if the woman was a witch. She was stripped, tied with ropes, and thrown into the sea. If she floated, she was guilty and would be burned. If she sank, she was innocent – but dead.

“There was no legal basis for such a test,” says Hagen.

All acquitted

Schønnebøl did not accept confessions that were made following torture. He questioned the accused again. Then the women told of the torture, that the witch stories were lies, and that they had been forced to name others.

“Schønnebøl heard their horrific descriptions of the torture used. He was quick to acquit them then,” says Hagen.

The four women and six children were acquitted.

The mothers of several of the children had already been burned as witches. Schønnebøl demanded that their daughters be taken care of by local families and treated as their own children.

In later court cases, he awarded compensation to the accused for their time and suffering in prison.

Schønnebøl also rejected burning at the stake as a method of punishment, which had no basis in Norwegian law.

The two women he sentenced to death in 1656 were beheaded.

“It sounds absurd, but beheading was actually a milder sentence,” says Hagen.

Stood out from his colleagues

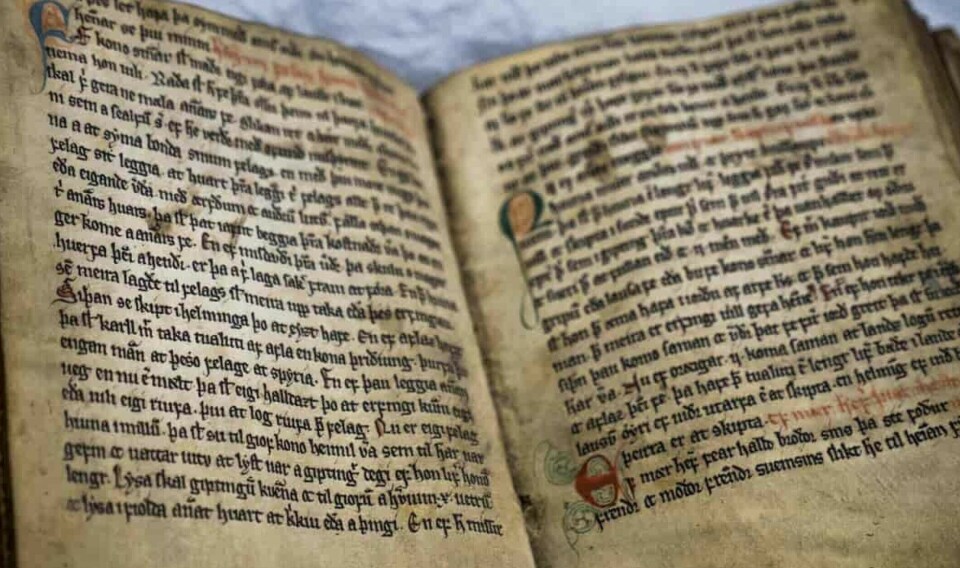

Hagen has reviewed court records, letters, and documents.

These records do not reveal what Schønnebøl thought and felt about the trials. The historian had to interpret the text and his decisions to get a picture of the man.

Most viewed

“He stood out from the other district court judges in the way he conducted the cases. He was committed to following the law, but it seemed there was a humanistic ideal behind it. Eventually, it seems that he also became sceptical of the belief in witches,” says Hagen.

Norwegian Supreme Court judge Aage Thor Falkanger has written a book about judges in Northern Norway.

He reports that not everyone was satisfied with how Schønnebøl practised the law. A colleague of his believed that hardly any witches would be burned at the stake if they were not threatened into confessing.

Schønnebøl fought against strong forces. He was probably the first judge to be critical of the evidence in witchcraft cases, according to Falkanger.

Stopped the persecutions

Witch trials were carried out both by ordinary people who wanted to get rid of a troublesome neighbour and those who served the king.

"Resistance required extraordinary integrity in such a climate," writes Falkanger.

A new law was introduced in 1687 that legalised the burning of witches. In return, it became more difficult to accuse people of witchcraft.

“Schønnebøl’s pioneering efforts came through more strongly in the new law,” says Hagen.

But by then the brave judge had died.

He had ruled in 23 witchcraft cases. Two were sentenced to beheading. 18 women were acquitted and cleared of wrongdoing. Two received fines, and a young girl received a prison sentence.

Schønnebøl handled appeal cases in Finnmark only every third year. Hagen believes this was unfortunate for all the accused women who were sentenced to death in local courts.

Nevertheless, it was his judicial practice and criticism of the practices of the time that had ripple effects.

Other judges followed Schønnebøl's lead and adopted his way of interpreting the law. He influenced those who came after him, both in Finnmark and the rest of Norway.

“Schønnebøl put a halt to the violent persecution of people in Finnmark,” says Rune Blix Hagen.

References:

Falkanger, A.T. 'Lagmann og lagting i Hålogaland gjennom 1000 år' (District court judge and district court in Hålogaland through 1,000 years), Universitetsforlaget, 2007. ISBN: 9788215011356

Hagen, R.B. 'Ved porten til helvete. Trolldomsprosessene i Finnmark' (At the gate to hell. The witch trials in Finnmark), Cappelen Dam, 2015. ISBN: 9788202314460

Hagen, R.B. '«Ingen udediske mennesker skal stå til troende»– Lagmannsdømming i nordnorske trolldomssaker 1647–1680' (Judgments at regional level in north Norwegian witchcraft trials 1647–1680), Heimen, vol. 52, 2015. (Abstract)

Trolldomsforordningen av 1617 (The Witchcraft Ordinance of 1617), Norwegian History, University of Oslo.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no