The metre is 150 years old: Here lies Norway's copy

Clever minds in France had had enough. It was time for a common measurement system.

Nowadays, we can measure things with extreme precision all over the world.

But it hasn't always been like that.

Measurements varied between different countries, cities, and people.

"There was probably a lot of disagreement," says Hans Arne Frøystein from the Norwegian Metrology Service.

Now, we agree down to the millimetre.

What happened?

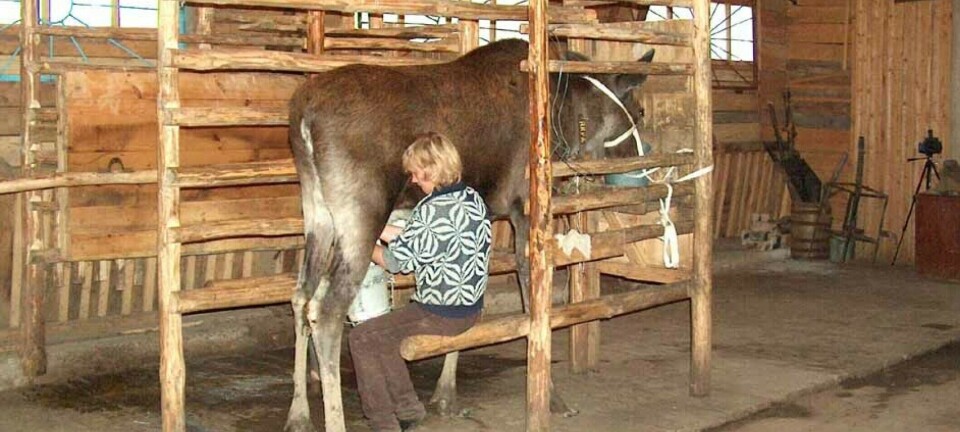

Using the body as a ruler

In the past, there was no common standard of measurement. So what did people use?

"The body," says Frøystein.

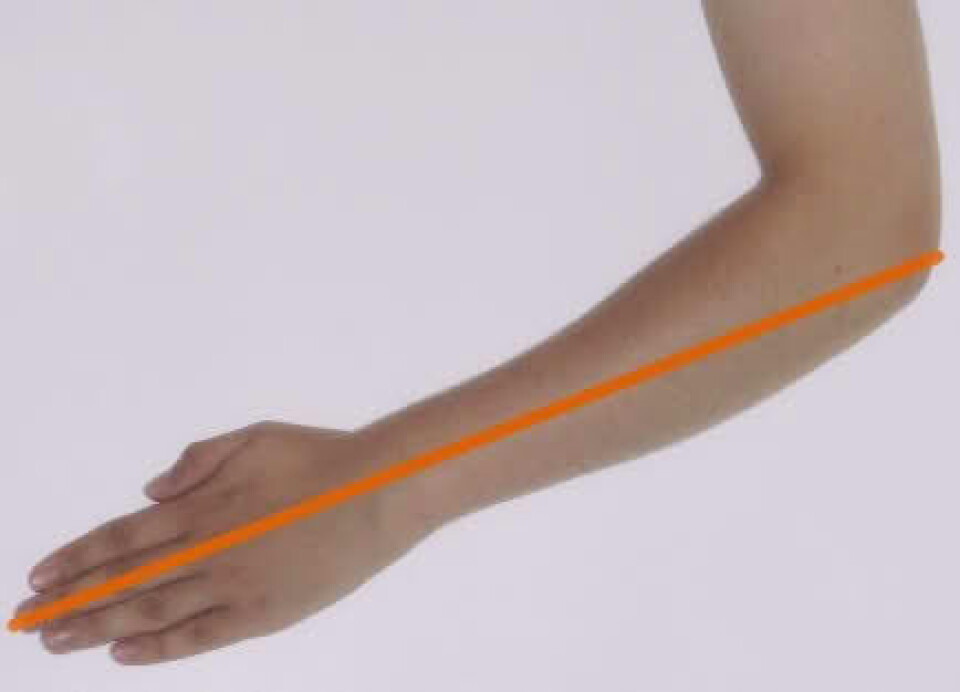

A foot was roughly 30 centimetres, an ell stretched from the elbow to the fingertips, and an inch was the width of a thumb.

But people's bodies are different. That caused problems.

'This silk scarf is an ell,' one person might claim.

'No, it's only half an ell,' another might reply.

Eventually, France’s brightest minds decided enough was enough.

The world would get a unified system of measurement – one standard for all.

"And we did. This year marks 150 years since the metre was introduced," says Frøystein.

Measuring the Earth

"How was the metre defined?"

"They used the length of the Earth," says Frøystein.

It might sound odd today, but the concept was simple:

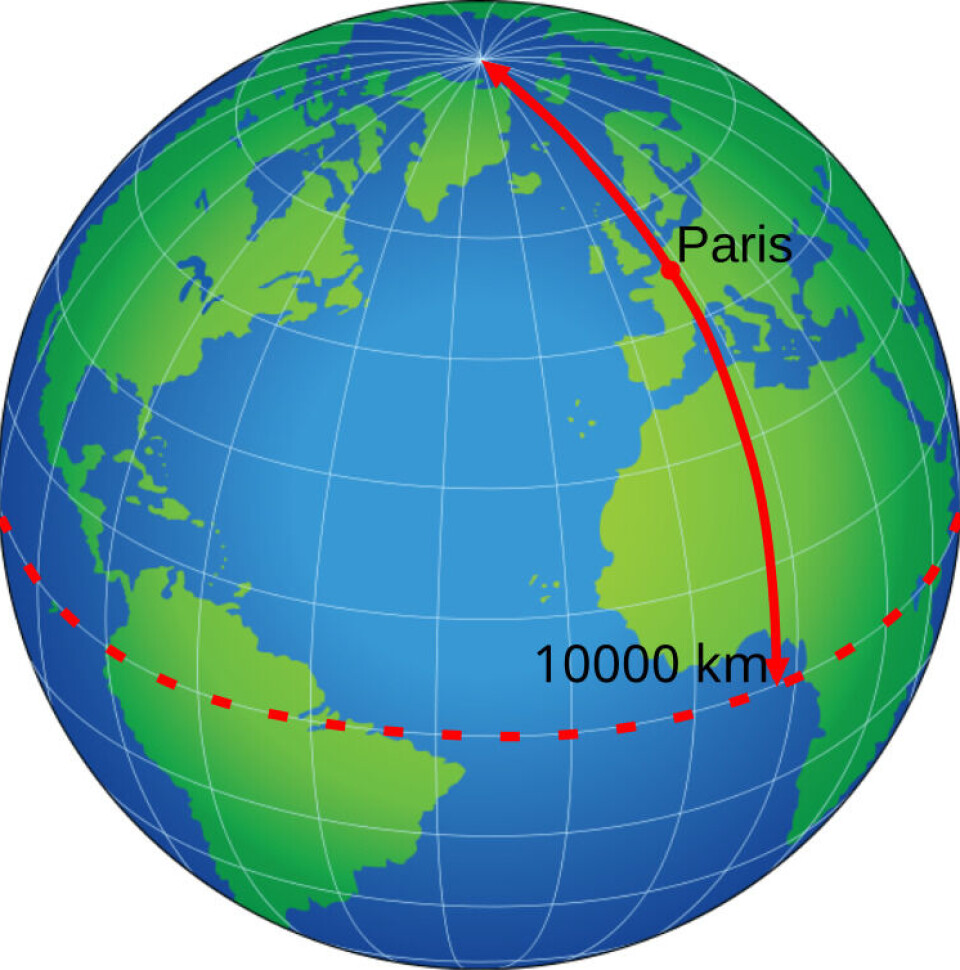

One meter would be a tiny slice of the distance from the North Pole to the equator – precisely one ten-millionth of that span.

This was in the 1700s.

"And no one had even reached the North Pole yet," he says.

A platinum standard

French scientists decided to first measure a distance they were familiar with:

"The distance between Dunkirk in France and Barcelona in Spain," says Frøystein.

Using that as a baseline, they calculated the distance from the North Pole to the equator.

Once that was done, they created an exact metre made of shiny platinum.

The metre was born, and copies were sent to different countries.

"The original is safely stored in Paris," he says.

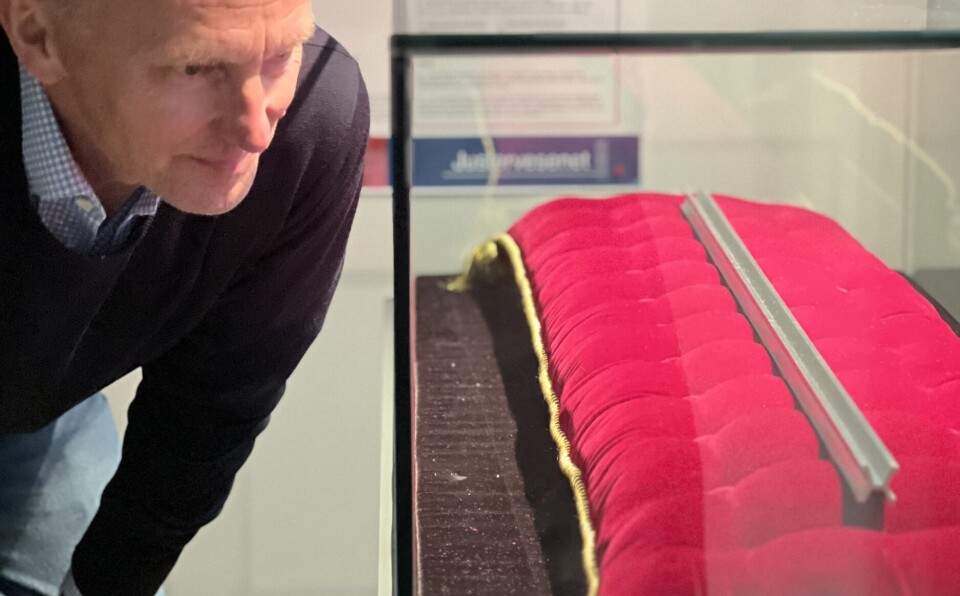

Norway's copy rests on a red velvet cushion at the Norwegian Metrology Service.

And that's where it will stay.

The metre stick is retired

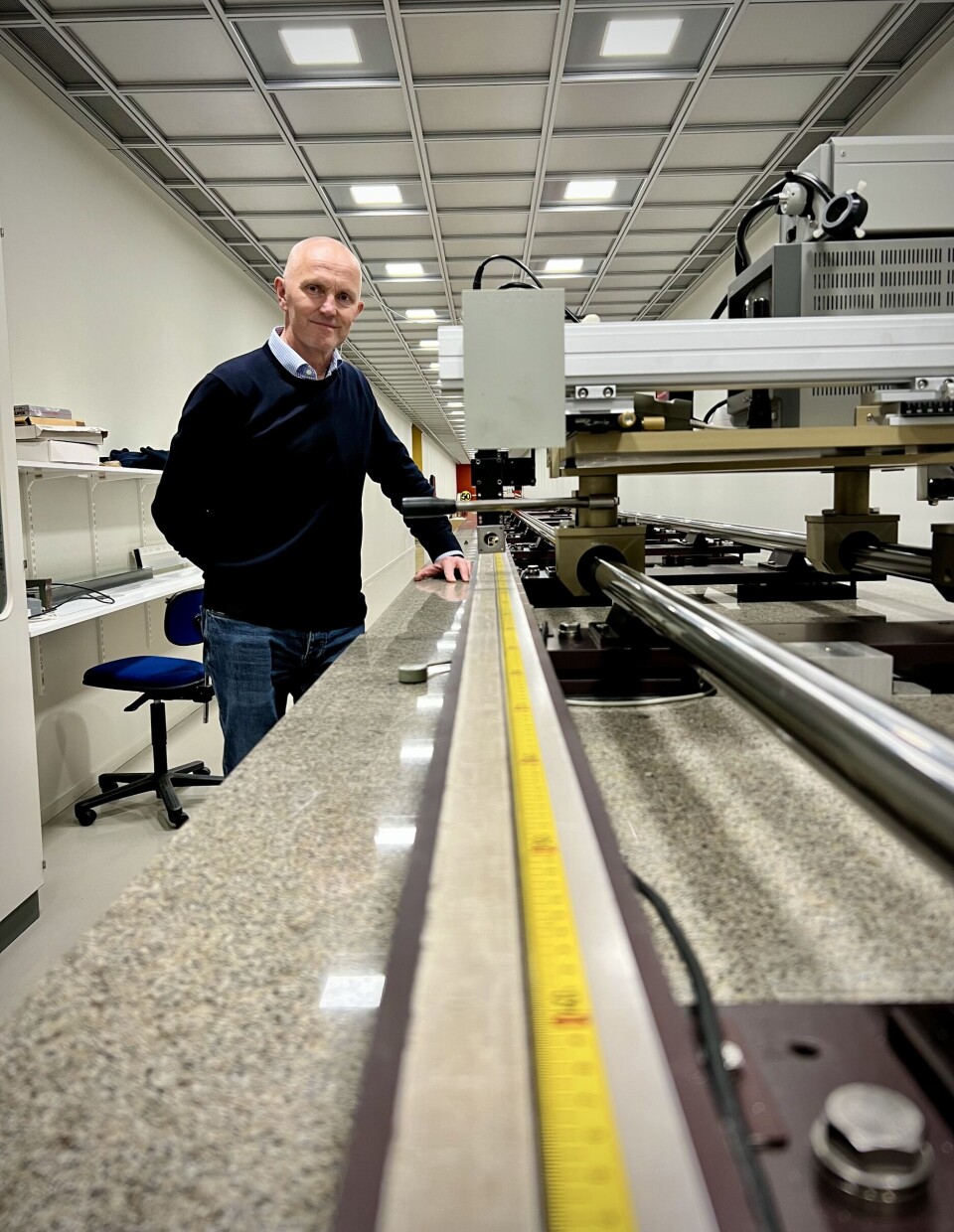

"Now it's all about lasers," says Frøystein.

The traditional metre stick has been retired – we simply don’t need it anymore.

Lasers offer far greater precision than any physical measuring tools.

A metre is now defined as the distance light travels in a tiny fraction of a second.

"That allows for incredibly accurate measurements," says Frøystein.

Otherwise, things can go wrong.

Most viewed

Imagine building a bridge from both ends.

If the tools on either side don’t agree on the length of a metre, the two halves could completely miss each other.

Will a metre still be a metre in 500 years?

"Does the entire world use the same measurement system?"

"In a few countries, like the US, they differentiate between what's used at work and in everyday life," says Frøystein.

For instance, American carpenters still use inches when talking about the length of a plank.

"The reason is probably that changing that system now would be difficult," he says.

"Do you think the metre will still be the same length in 500 years?"

"It's hard to say for sure," he says.

He believes it will be the same length.

"But maybe we'll be able to measure it even more precisely than we can today," he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.