A mystery solved: Who killed the Swedish king Charles XII?

For centuries experts have debated who killed the Swedish King Charles XII. A new Finnish study in which the researchers shot at artificial skulls completely refutes the idea that he was killed by his own war-weary soldiers.

The war hungry King Charles XII was King of Sweden, which then included present day Finland, from 1697 to 1718.

He had tried to invade Norway in 1716 but was forced to retreat. A new attempt to take Norway in 1718 ended with the deadly shot.

Who shot the King has been a hot topic of debate ever since.

The researchers at the University of Oulu in Finland fired several projectiles from "Norwegian" musket guns and black powder cannons at artificial human skulls.

They were to emulate the Swedish king's skull.

The researchers have now concluded that the shot that killed Charles XII at Fredriksten fortress in the Norwegian border town Halden on 30 November 1718 could not possibly have been fired at close range by one of the king's own Swedish soldiers.

Projectile was at least 20 mm

The researchers also consider it highly unlikely that the king was killed with a lead ball from a musket.

It would have required a significantly larger musket ball to cause the hole in the Swedish king’s head.

The ball must have had a diameter of well over 20 mm, according to the Finnish forensic pathologists. The injuries to the king's head are consistent with a projectile that could have been fired by Norwegian soldiers at a range of 200 metres and hitting at a speed of about 200 metres per second.

The study of the shot in Halden 300 years ago by the Finnish researchers was recently released in the PNAS Nexus journal, which is published collaboratively by the National Academy of Sciences in the USA and the University of Oxford in the UK.

Hit by grapeshot?

Finnish anatomy researcher Juho-Antti Junno believes that a Norwegian grapeshot might have been what struck Charles XII.

Grapeshot is a projectile consisting of many balls contained in a piece of cloth or metal cylinder. This type of ammunition was particularly common in the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Before we started this study, I assumed that it had to be a lead musket ball that killed the king,” Junno states in the Swedish journal Forskning & Framsteg.

“But after we had shot the projectiles at the artificial skulls and then examined the skulls in a CT scanner, we saw that the hole could not have been made by a lead ball. Nor could it have been made by a button.”

The projectile must have been a larger and not made of lead.

The theory that Charles XII’s skull was pierced by a round uniform button after being shot at by a war-weary Swedish soldier, was posited many years ago. The hypothesis has since been debunked.

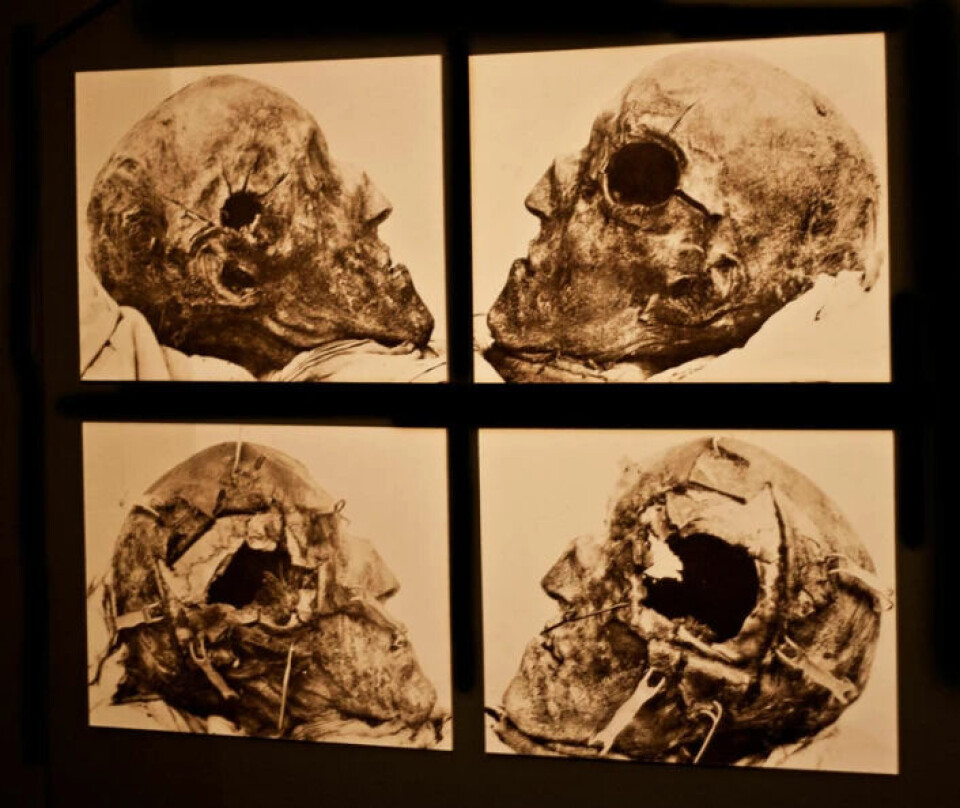

X-ray of the skull

Junno and his forensic research colleagues at Oulu University set out to study the murder of Charles XII in Halden, simply because they were able to put together a research team – consisting of a radiologist, a forensic anthropologist, a bioarchaeologist and an expert in forensics – where everyone felt that this was an appropriate challenge to tackle as researchers.

“Our experienced radiologist was able to determine that the X-ray images obtained from opening the king's grave in 1917 contained no traces of lead.”

“Despite the quality of the X-ray images not being that good, lead would have left traces on the image that would be impossible to miss,” says Junno.

The holes shot into the artificial skulls by the Finnish researchers were significantly larger than if it had only been a uniform button passing through the skull.

Tomb opened earlier

After his sudden death at Fredriksten fortress in Halden in 1718, the king's body was transported home to Sweden.

He was buried in Riddarholmen Church in Stockholm.

Already 28 years after the king's death, the grave was opened for the first time and the body of the king was examined more closely. The aim also then was to clarify who had killed him.

Charles XII's tomb was reopened in 1799 and 1859.

At the very last grave opening in 1917, the king’s skull was X-rayed.

References:

Juho-Antti Junno et.al.: The death of King Charles XII of Sweden revisited. PNAS Nexus, 2022.

Lukas Lindström: Finländska forskare löste trehundraårigt mysterium: Karl XII dödades av fiendekula (Finnish researchers solved a three-hundred-year-old mystery: Charles XII was killed by an enemy bullet). YLE, 2022. (in Swedish)

Mats Karlsson: Ny analys: Norsk eld dödade Karl XII (New analysis: Norwegian fire killed Charles XII). Forskning&Framsteg, 2022. (in Swedish)

Oulon Ylipisto: Tutkijoiden tekemät koeammunnat varmistivat Kaarle XII kuolleen vihollisen luotiin (Test firings by researchers confirmed that Charles XII was killed by an enemy bullet), 2022.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no