Norwegian Musketeers had to learn 43 moves to fire one shot

Young boys with imprecise weapons received training based on science and a French manual.

The low point in Norwegian history was the year 1536.

That’s when the Danish King Christian III declared that ‘Norway shall henceforth not be or be called a separate kingdom, but part of the Kingdom of Denmark and under the crown of Denmark forever’.

Then the Danish kings threw themselves into eight wars in quick succession, according to norgeshistorie.no.

The first two wars in the south of Europe did not involve Norwegian soldiers. The king did not want to give the Norwegians weapons.

When the Swedish army occupied Trondheim in central Norway and marched into Eastern Norway in the 1560s, the Norwegians did not resist. Some hoped that the Swedes would free the country from Danish power.

But the Swedes plundered and ravaged the country. In the end, they were chased out by forcibly mobilized Norwegians from the west coast and by Oslo residents who burned down their own city.

Drank the king's beer

In the fourth war, the king wanted to mobilize Norwegian farmers to march into Sweden. It didn’t go too well. Many refused to show up, and those who came drank the king's beer and went home.

The king took action. He punished peasants who refused military service and executed some of them.

Then, in 1628, the Norwegian army was established.

Sweden had become a military power and seized large areas of land from Norway and Denmark. The king needed Norwegian soldiers both for defence and attack purposes.

The king gave his son-in-law, Hannibal Sehested, the job of building the Norwegian army.

From mercenaries to farm boys

“To begin with, Sehested imported Dutch and German officers, but eventually trained our own officers in Norway,” says Mads Berg. He is a historian and lecturer at the Armed Forces Museum of Norway.

The Norwegian army first consisted of enlisted soldiers.

“They came from various places, including abroad. But they were expensive and it took a long time to recruit them. That’s why they weren’t used in peacetime, but just hired when there was war,” says Berg.

Then farmers' sons and farm workers had to become soldiers. The country was divided into regions, where four farms had to provide for one soldier and pay for his food and equipment, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.

“They had to keep the soldier alive, so that he could attend duty and exercises,” says Berg.

War based on mathematics

When the soldiers were called for, they went to their local camp. There they met the officers who had been schooled in the regulations and on the manuals.

The boys were given muskets and thus became musketeers in the Norwegian army.

They were drilled in handling the weapon and in ways of fighting. The faster and safer they were, the better they fared in battle.

“There was a big difference between the aristocratic officers, who were supposed to develop new knowledge and lead the battles, and the soldiers, who were supposed to be the cogs in the wheel,” says Berg.

Officer training was based on science and especially mathematics.

This was a time of major scientific breakthroughs and rationalism. People expected to understand and control nature using human reason and logic.

Officers became engineers

“The military version of this idea was that people would literally subjugate the whole world with the help of engineering thinking,” says Berg.

Technical development happened rapidly. The military rethought how to use weapons and train officers.

“At the Norwegian Military Academy they learned to write, do technical drawing and to make maps. They learned to sketch harbours and forts. And they received training in building weapons, roads, bridges and buildings,” says Berg.

Technical knowledge was a necessity.

“Building a cannon required engineers. To use the cannon required a solid knowledge of mathematics. Managing a department, buying food and paying salaries required the ability to keep track of finances,” says Berg.

The military education of engineers and economists was the top priority. Education also made it possible for soldiers to climb the social ladder, even without coming from an aristocratic or wealthy family. When civil education came later, these professions were called civil engineer and civil economist.

“The first half of the 19th century was a heyday for officers, and it was built on knowledge,” says Berg.

Handbook for the musketeers

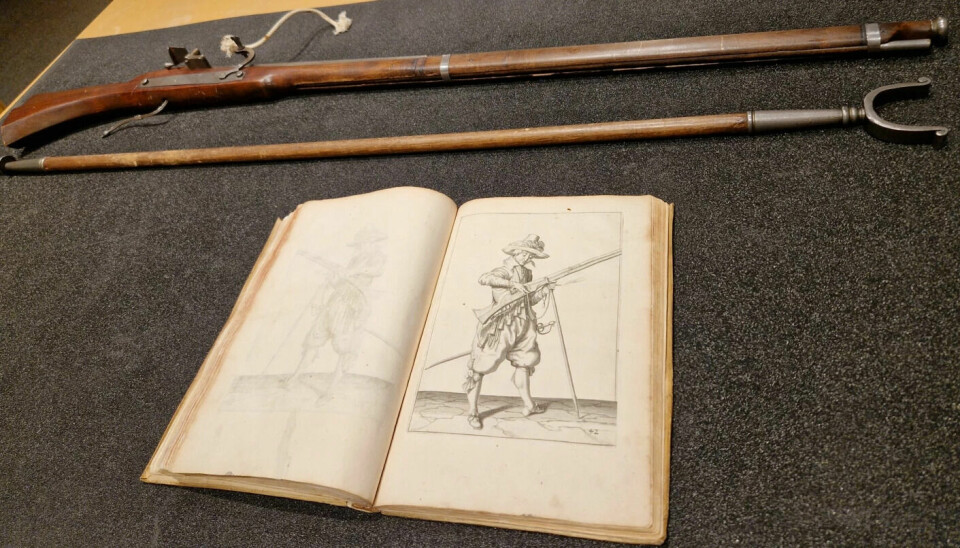

Berg pulls out one of the very first books of regulations. He chose this item when asked by sciencenorway.no to find a treat from the museum.

The book is called Maniement d'armes, d'arqvebuses, mousqvetz, et piqves. It was printed in 1608.

“This is a handbook for young and inexperienced musketeers in the use of muskets,” says Berg.

The handbook was written at the behest of the French king and was translated into several languages.

“Military science was international. Countries learned from each other and used each other's methods,” says Berg.

The handbook was not translated into Norwegian, but came to Norway in a French edition. The officers learned the procedures and passed on the knowledge in training the private soldiers.

Burning fuses and dangerous gunpowder

The manual is easy to use. It has drawings for every move the soldier has to make with the heavy weapon.

And the manual is thorough.

“To fire a shot with a musket, the soldiers had to go through 43 steps,” says Berg.

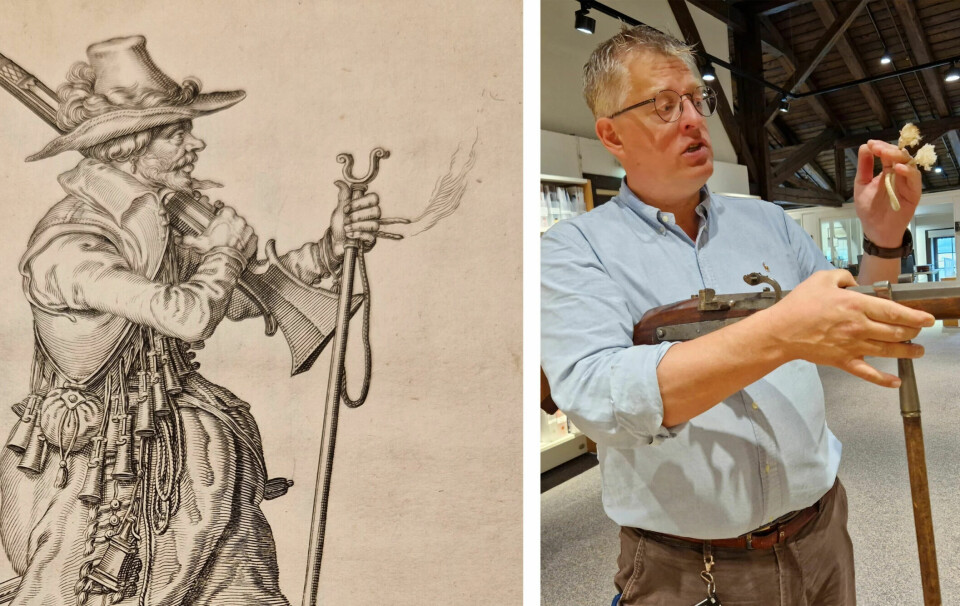

He takes out a musket and demonstrates.

With a burning fuse in his left hand, the musketeer arranges the gunpowder with his right hand.

“It was important to keep those things apart. The point of gunpowder is that it’s explosive,” says Berg.

Gunpowder in a small bottle

The gunpowder hung in a belt across the soldier’s chest.

“The belt held twelve bottles, called apostles – because Christianity was the soldiers’ bedrock. Each bottle had enough gunpowder for one shot,” says Berg.

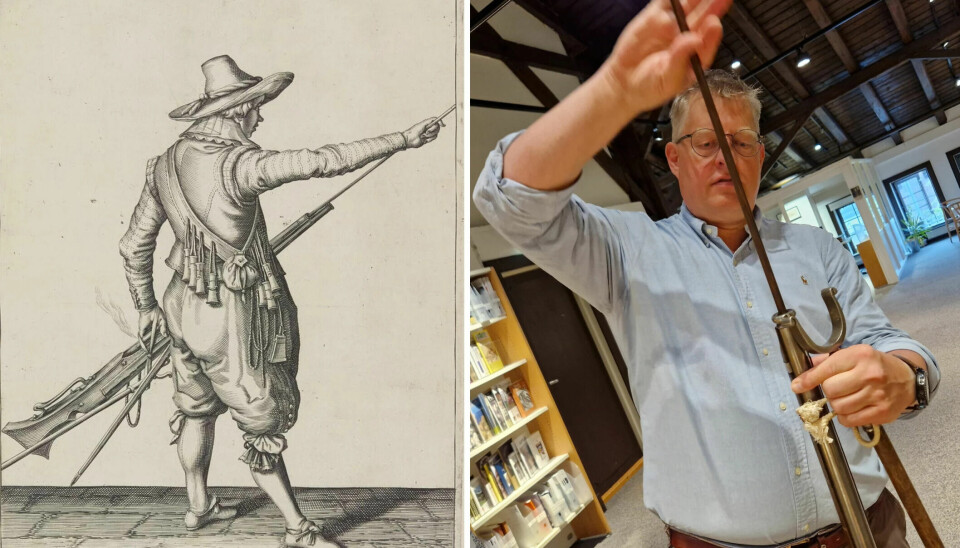

They poured the gunpowder into the barrel and then inserted a projectile. Both parts were pushed down well with a ramrod.

With the bullet and gunpowder in place, the musketeer took another bottle. In it there is a small amount of gunpowder, which he pours into a flash pan, right next to the trigger.

“Then the soldiers get orders to touch the fuse to it. First, we blow away gunpowder residue, then we adjust the fuse and touch the fuse to the flash pan,” says Berg.

Like a knuckleball

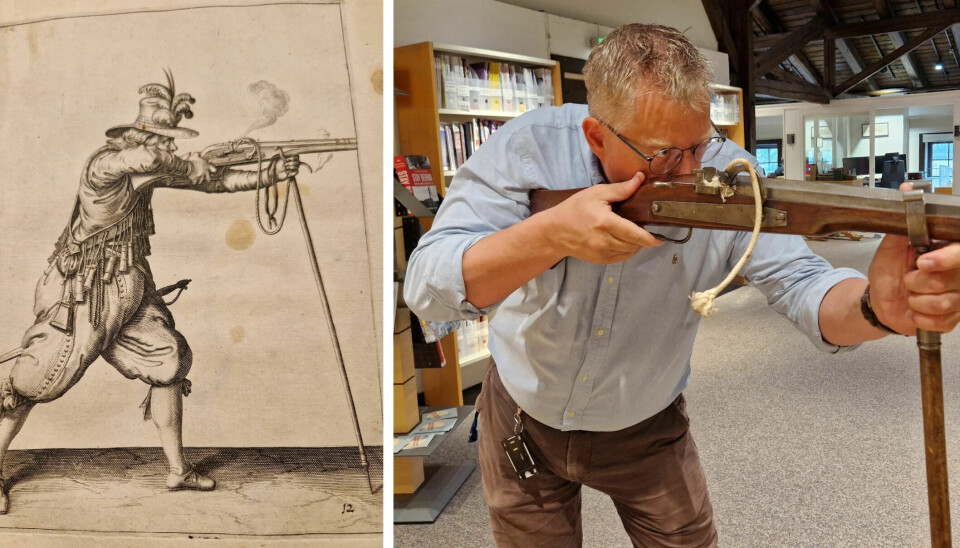

The gunpowder in the flash pan ignites and sets off the gunpowder in the barrel, causing an explosion.

“The pressure from the explosion sends the bullet out of the barrel – more or less straight ahead,” says Berg.

This was before the time of rifles, which have spiral impressions called rifling in the barrel that give the bullet spin and a straight trajectory. The musket is not very accurate, and the bullets and have a short range.

“The musket barrel has smooth walls, which means that the ball flies a little like a knuckleball, wobbling a bit back and forth in the air. But when you have a hundred soldiers standing close in a row and shooting, then a hundred bullets will hit the enemy, whose soldiers are also standing in a row, often only 70 to 80 metres away,” says Berg.

The entire process of preparing and loading the musket takes less than a minute.

“If they spent less time than the enemy soldiers, things went better for them. If they trained and drilled the procedures, there were fewer accidents and more hits,” says Berg.

150 years of war

When the shot goes off, a large cloud of smoke comes out of the muzzle.

“This isn’t smokeless gunpowder, so there’s a lot of smoke. That didn't make it any easier to hit the enemy.”

The musketeers participated in wars against Sweden until 1721, when peace was made between the Nordic countries.

“There were 150 years with a lot of war. The Norwegian army made a really good effort when the Swedes took Trøndelag in the middle of the 17th century,” says Berg.

“Norwegian soldiers were eager to fight for Norwegian territory. But they weren’t as eager to participate abroad.”

The manual with 43 steps for firing a shot is not the only regulation manual at the Armed Forces Museum.

Rules for everything

The archives contain row upon row of regulation manuals. The also include the military journals of the rules and practices discussed by the officers, and not least, the new methods that were being used in other countries.

“There are rules for who should greet whom, and in which way. And how many shots you will fire if a high-ranking officer or a member of the royal family sails into your fort,” says Berg.

Many rules deal with how to wield a sabre, specifically how to cut down the enemy in the best possible way.

The drum and trumpet regulations are comprehensive. The drummers had to know dozens of different melodies.

When the musketeers stood close together and fired, there were a lot of explosive blasts. The cannons made noise. The drums and trumpets told the soldiers what to do.

“We take good care of these regulations. They’re a national treasure,” says Berg.

References:

Øystein Rian: Danskekongens kriger 1537–1660 (The Danish King's Wars 1537–1660). Norgeshistorie.no 2015/2023.

Finn Erhard Johannessen: Den dansk-norske militærstaten (The Danish-Norwegian military state). Norgeshistorie.no 2015/2022.

Hans Jacob Orning: Norge blir et lydrike (Norway becomes a puppet state), Norgeshistorie.no 2015/2020.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no