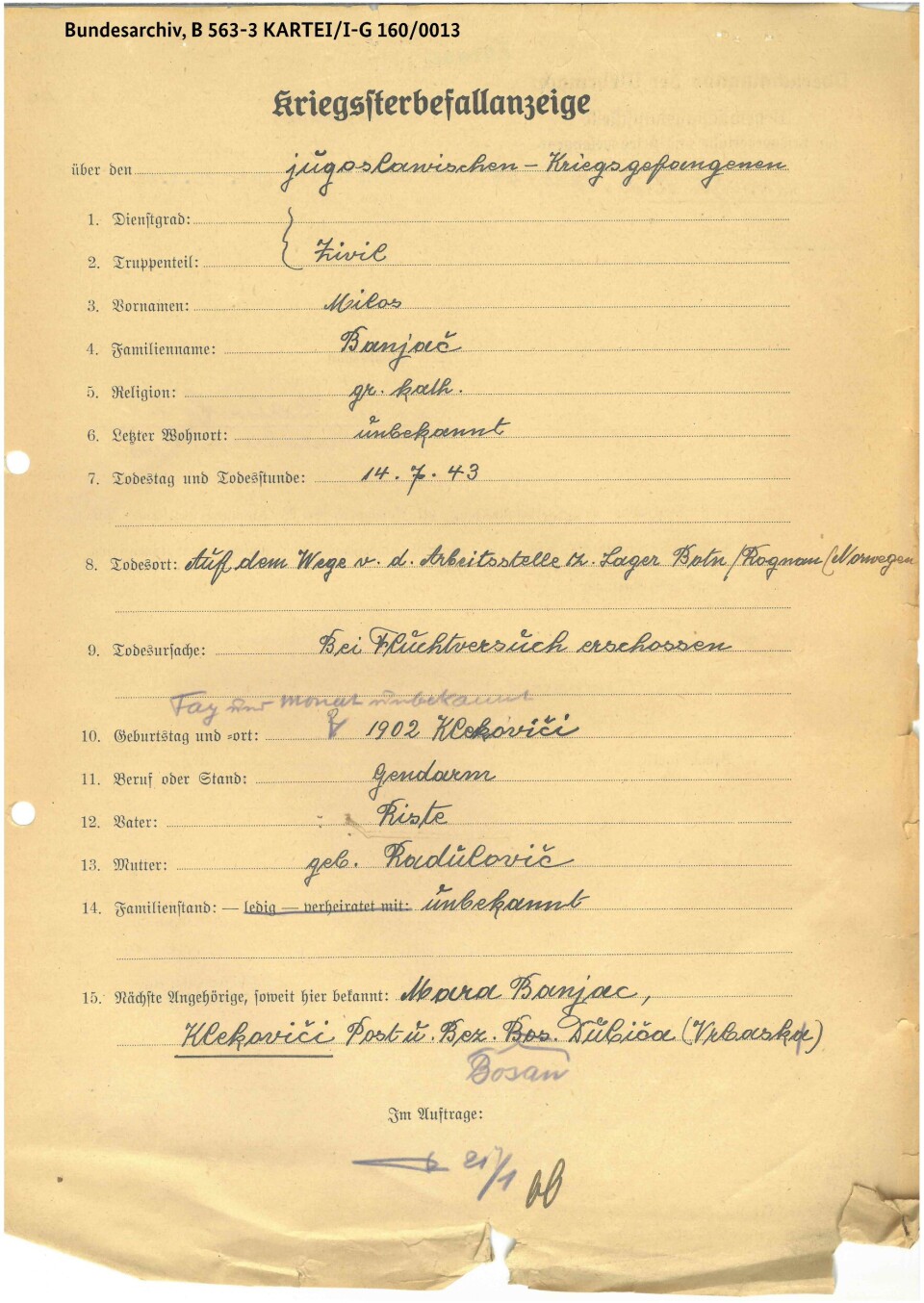

Miloš Banjac was shot and killed by the Germans at Rognan on 14 July 1943.

His brother Marjan knelt by his dead brother.

Using Miloš's blood, he drew a cross on the rock face.

This cross is still regularly repainted with red paint.

The brothers had been sent to Northern Norway as prisoners to build a road.

This stretch of road is called the Blood Road.

This part of Norway's war history is not well enough known, according to a conservator.

Yugoslav prisoners were sent to Norway to die

Researcher says that the mortality rate in some Norwegian concentration camps was on par with the worst in Europe.

Road standards in Northern Norway were poor and underdeveloped when the World War II broke

out. The vast majority of the prisoners who were sent to Norway to build roads

were from the part of the former Yugoslavia that we now call Serbia.

“The story of how bloody the road construction in Northern Norway was during the Second World War isn’t well known,” conservator Ronald Nystad-Rusaanes at the Blood Road Museum in Nordland county says.

The local residents in the town of Rognan want people who drive past to be reminded of the brutal treatment that prisoners were subjected to here. That is why they regularly repaint the cross that Marjan drew.

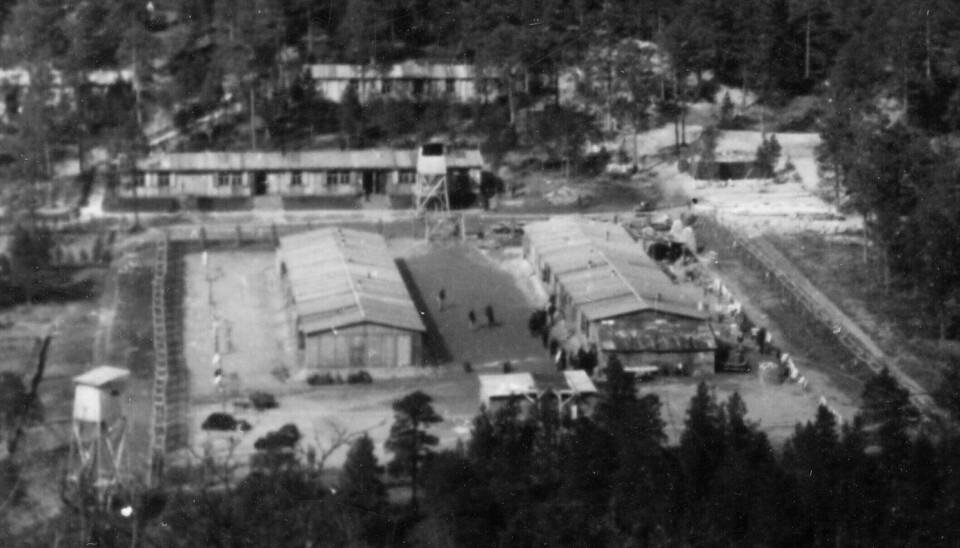

The story of the two Yugoslav brothers who were prisoners in the Botn camp contributed to the 1.5 kilometre stretch between Botn and Saltnes villages being referred to as the Blood Road. This stretch is located just outside the settlement of Saltdalen in Nordland county.

Not very known

Ronald

Nystad-Rusaanes is conservator at the Blood Road Museum, which

is located in an old German barrack outside Rognan.

He shows the cross to the sciencenorway.no journalist exactly 80 years after Miloš was shot here.

What happened here is a little-known part of Norway’s war history, according to Nystad-Rusaanes.

Five camps in Northern Norway

While the vast majority of us know the history of the concentration camps in Auschwitz and Birkenau, far fewer know that Norway had any such camps.

Some of them had a higher rate of mortality than the more famous camps in Europe.

The camp in Botn is one of five such camps in Northern Norway. The others were located in Korgen, Osen, Beisfjord/Bjørnfjell, and Karasjok.

In Botn, where the Banjac brothers were prisoners, 61 per cent of the prisoners died in the first year.

The greatest number of prisoners died in the village of Beisfjord.

Overall, 82 per cent of the prisoners of war lost their lives there.

On average, about 70 per cent of the prisoners died in the five camps.

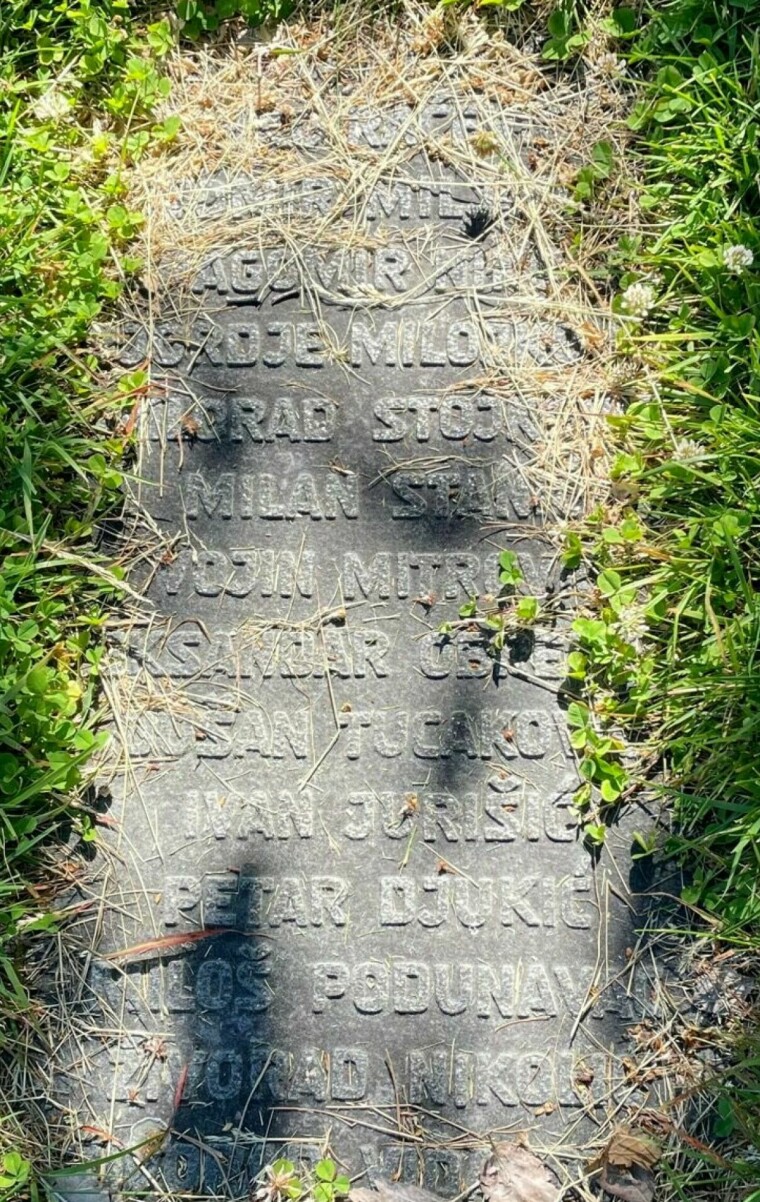

A commemorative plaque with the names of some of the Serbian prisoners who lost their lives in Botn during the war is mounted into the ground at the war cemetery.

Sent here to die

“There are a lot of ‘blood roads’ in Northern Norway,” Michael Stokke, a researcher at the Narvik War and Peace Centre, says.

The Botn camp is one of the camps he has decided to call a concentration camp. In the past, historians have referred to them as prison camps.

Stokke is writing his PhD on Yugoslav prisoners in Norway during the war.

“The men who came to these camps were sent here to die. That’s why I believe the term concentration camp can be used,” Stokke says.

Nearly half of the approximately 2,000 prisoners who died were shot. The rest were abused until they succumbed or died of disease and starvation.

“In some Norwegian concentration camps, the mortality rate was on par with the worst in Europe,” he says.

Buried in mass graves

Both in Botn and in Beisfjord, prisoners were massacred and buried in mass graves because the German guards suspected they had typhus.

“Not even the people who live in the area around Rognan know how brutal the events that happened here were,” Nystad-Rusaanes says.

But the neighbours to the camp discovered the cruelty of the SS soldiers who ruled the camp in the first year, he says.

“Witnesses from that time have said that the prisoners could be shot when they went to or from work. When the families in Botn ate dinner in the afternoon, they often heard gunshots. Then silence would descend around the dinner table,” he says.

When Nystad-Rusaanes is asked to select one object from the museum at Rognan, he chooses the gate to the Botn camp.

“The gate is a tactile witness to the times that reminds us all of how on the edge life can be between war and peace, life and death,” he says.

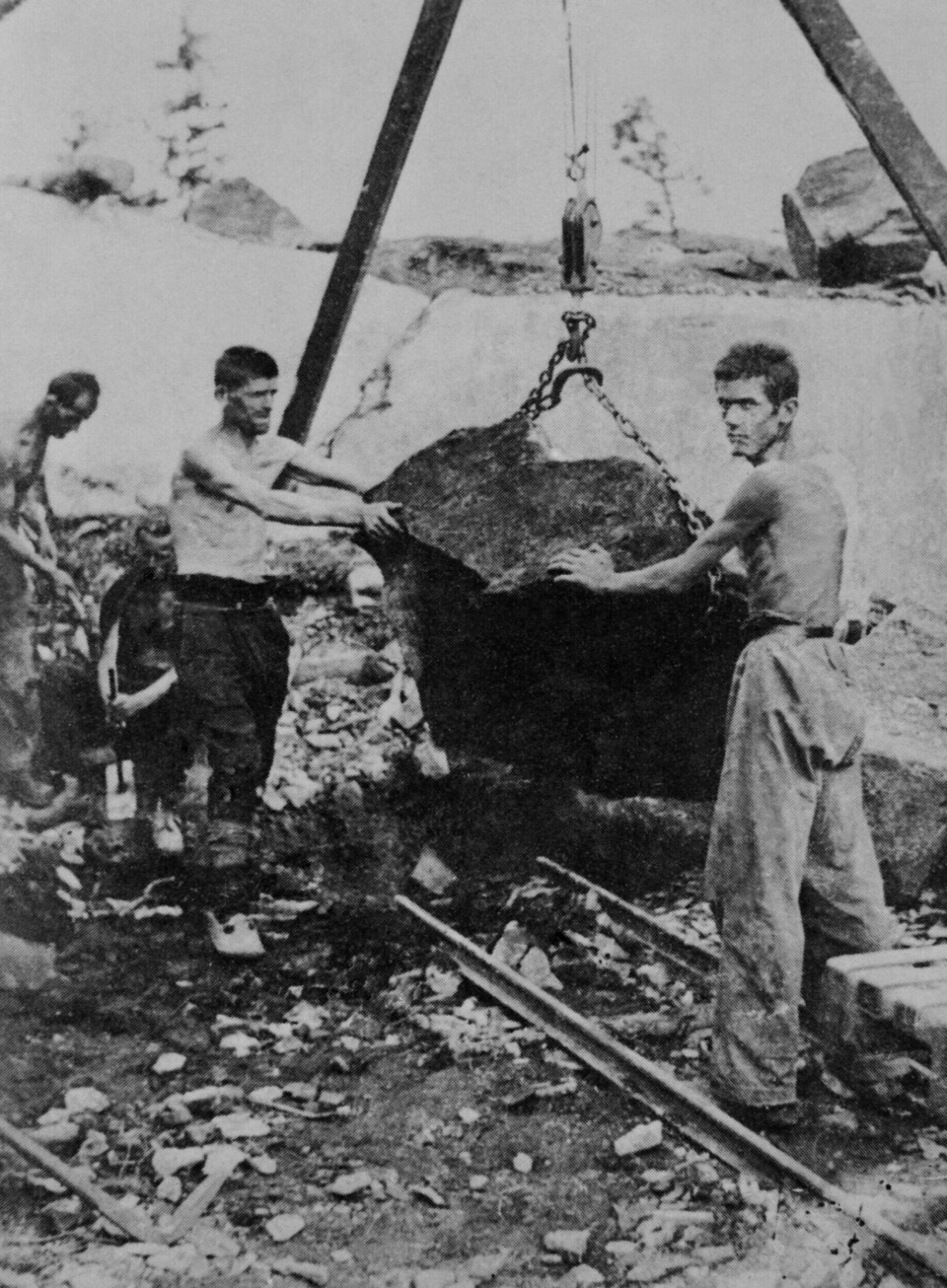

Hard work

The Banjac brothers were among the 463 Yugoslav prisoners on board a ship that docked at Rognan in July 1942.

They had been sent to Norway to build roads.

It was hard work.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration cooperated with the German occupying power to blast rock, which the prisoners then had to lift into trolleys and cart away.

Not prisoners of war

Unlike the Soviet prisoners of war, the Yugoslavs were not prisoners of war. They had been arrested as enemies of the regime in their home country and had been sentenced to death.

Without prisoner of war status, they were not protected by the Geneva Convention, which regulates how prisoners of war should be treated.

The SS referred to the Serbs as murderers and bandits who deserved to die, writes norgeshistorie.no (link in Norwegian).

The SS was an armed squad that was assigned to serve as bodyguards for Adolf Hitler.

They were going to be killed anyway

Since the prisoners were going to be killed anyway, they could just as well be sent to Norway to build roads first.

Boys as young as 14 were sent from Yugoslavia to Norway. SS instructions were to treat them in the harshest way.

And so they were.

Of the 463 prisoners who arrived at the quay at Rognan in July 1942, only 171 were alive the following year.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration agreed to use prisoners

It was difficult for the Germans to transport military equipment on the bad roads in Northern Norway. They initiated several road projects, enlisting the Norwegian Public Roads Administration to do the job, with prisoners as the labour force.

“The Public Roads Administration even built the prison camps,” Michael Stokke says.

Stokke has interviewed the Yugoslav prisoners in Norway. They believed that the Public Roads Administration employees did their best to bring the prisoners food and help them, and so were not very critical of them.

Stokke believes that it was probably just the director Andreas Baalsrud who made the wrong decision.

Baalsrud wrote in his notebook that the German order to use prisoners of war "must be understood", according to norgeshistorie.no (link in Norwegian).

“Initially, he probably thought that prisoners of war and not political prisoners would be used,” Stokke says.

The director was later deemed to have been too cooperative, or at best naïve and too concerned with getting roads built, according to norgeshistorie.no. After the war, neither the Norwegian Public Roads Administration nor Baalsrud were investigated.

Norwegian boys used as prison guards

The SS soldiers were not the only brutal prison guards in the camps in Northern Norway.

Nils Christie, a professor of criminology, has documented that ordinary Norwegians were among the worst prison guards in the camps in Northern Norway. They were young boys who volunteered for a well-paid job in what was called the Hirdvaktbataljonen (Hirden Guard Battalion).

They looked up to the German SS guards who came directly from the concentration camps in Germany.

The brutal mentality was transferred to Norway, Stokke believes.

“Some of the guards were indoctrinated to believe that they were superhuman and that the prisoners were worthless beasts,” he says.

Many prisoners tried to escape, but not very many succeeded. The guards received a bottle of liquor and a day off for every prisoner they managed to shoot.

“One of the Norwegian prison guards said that it was easier to shoot a prisoner than a cat. The conditions were horrible,” Stokke says.

He recalls that not all the guards were equally cruel. Some were passive, while others tried to help the prisoners.

Anyone can become a killer

Nils Christie argued in his 1972 book Fangevoktere i konsentrasjonsleire (Prison guards in concentration camps) that any person can kill. Ordinary people can be driven to extreme actions if they are put in extreme situations.

Sciencenorway.no interviewed Christie a few years before he died:

“I interviewed the prison guards, both those who’d done the most brutal acts, like murder and abuse, and those who had behaved normally. The key difference between them was whether the prison guards regarded the prisoners as fellow human beings or not.”

The guards who had perceived the prisoners as human beings – perhaps seeing pictures of their wives, children, and homes – behaved quite normally.

Those who were convicted of abuse and murder had not experienced this closeness. They had a limited understanding of the prisoners' situation and saw them almost as dangerous animals.

“This perception was how they felt liberated to do the most terrible things,” Christie said.

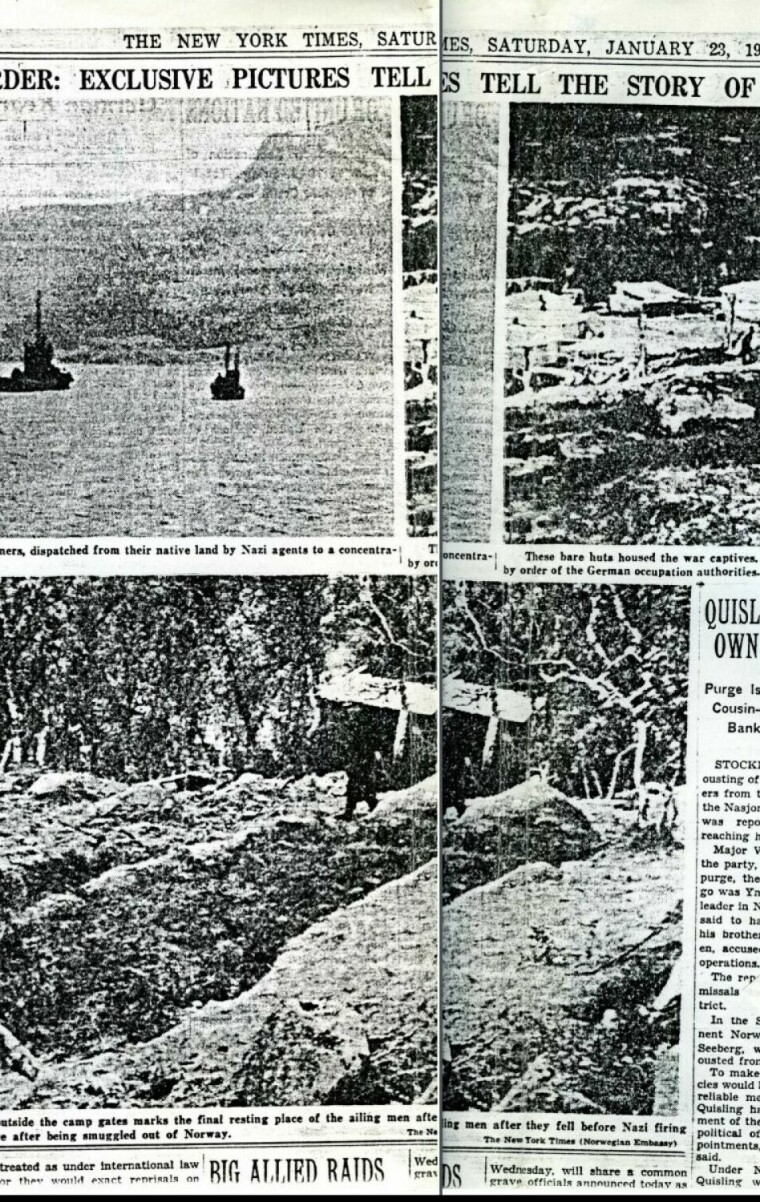

The New York Times told the story

Some of the prisoners managed to escape from the camps in Northern Norway and were able to make the world aware of the brutal events, Ronald Nystad-Rusaanes says.

Prisoners who managed to escape across the border to Sweden were interviewed by the Swedish press about what they had experienced in Norway. They brought photos of mass graves with them. The news spread to the international media.

“The world became seriously aware of what was happening in Northern Norway when The New York Times reported on the story on 23 January 1943,” he says.

"Exclusive pictures tell the story of mass murder in Norway," the American newspaper wrote.

The paper reported that prisoners "were brutally killed by order of the German occupation authorities."

This reporting caused the international Red Cross to get involved.

The organisation was initially told that these were not prisoners of war, so they could not take any action.

But the Red Cross continued to exert pressure, according to Stokke.

From terrible to bad

In the spring of 1943, the SS guards were removed and replaced with guards from the German army, the Wehrmacht.

Conditions improved somewhat in Botn and the other camps in Northern Norway, Stokke says.

The Serbian prisoners were eventually exchanged for Polish and Soviet prisoners.

“Conditions went from being terrible to just being bad. The Yugoslav prisoners received packages from the Red Cross with nutritious food, coffee, and tobacco starting in January 1944,” Stokke says.

The death toll dropped significantly.

The brother who survived

Miloš Banjac's brother was one of the survivors of the atrocities in Northern Norway. He returned home.

“After the World War II, Marjan Banjac became a winemaker in Yugoslavia,” Nystad-Rusaanes says.

Photos:

The red cross at Rognan: Siw Ellen Jakobsen

Serbian prisoners working on the Blood Road: Siw Ellen Jakobsen.

Memorial plaque with the names of Serbian prisoners who lost their lives in Botn: Siw Ellen Jakobsen

Facsimile of The New York Times 23 January 1943: the Narvik War and Peace Centre

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no