The first tourists who came to Norway were from the upper class.

Many were tired of ancient Rome or the mountains in Switzerland.

Then they experienced a culture shock at Norwegian farms.

European tourists experienced culture shock when they came to Norway in the 1800s

Tourists often slept in straw-filled beds or on a hard bench in a smoky living room.

As a relatively inaccessible country, it took some time before Norway became a major tourist destination.

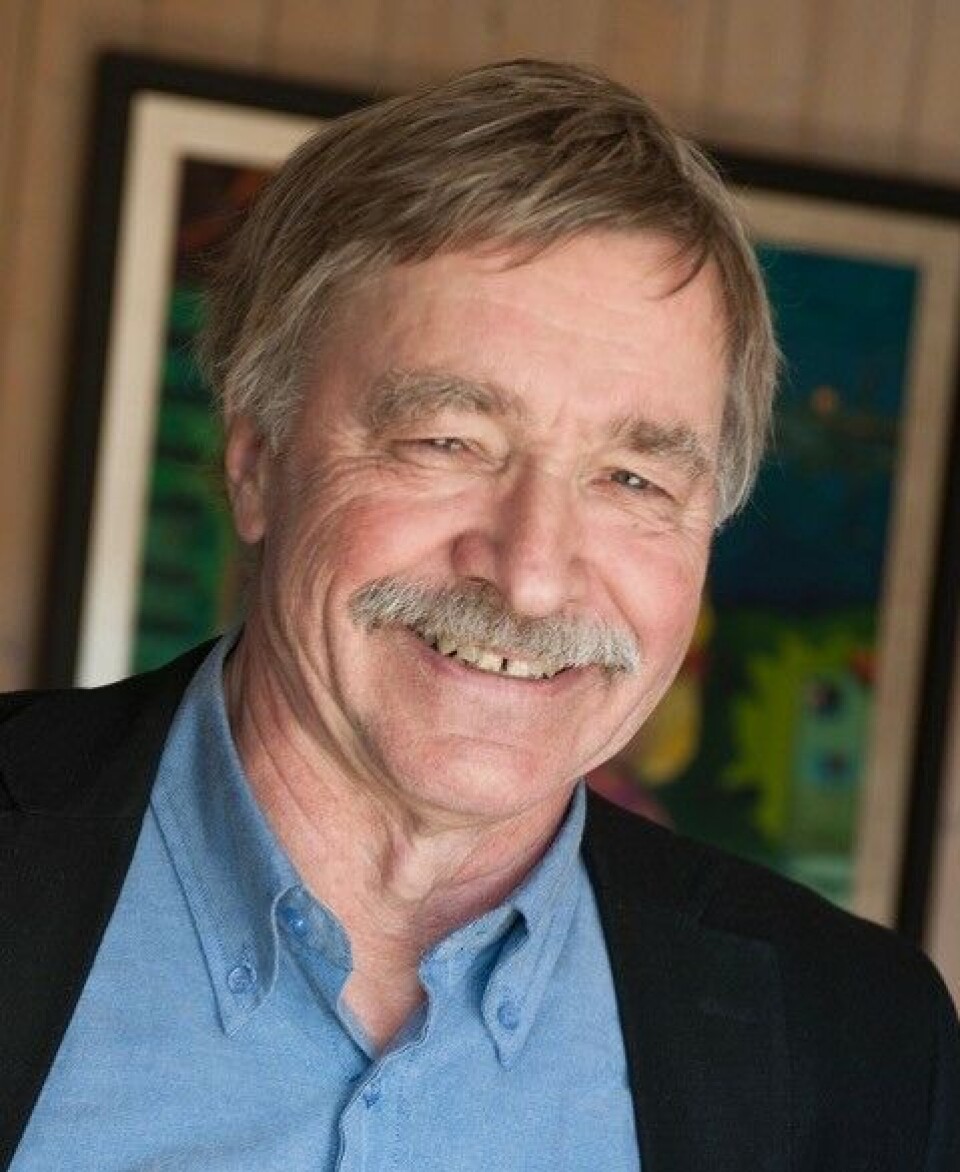

“There were no leisure travelers before the first tourists around 1800,” Professor Emeritus Bjarne Rogan tells sciencenorway.no.

But when tourists finally appeared from abroad, they got to experience very exotic modes of travel and accommodations, Rogan explains.

As a cultural historian at the University of Oslo (UiO), Rogan has researched transportation history, travel, and tourism in the 19th century.

“In the mid-19th century, tourism flourished,” Rogan says.

Fjords and mountains in Western Norway were popular.

Tourists often had to put up with being transported by uncooperative local farmers.

These ‘shuttle farmers’ were responsible for transporting travelers within a certain area and shared the task with other farmers.

It still took a while before the number of tourists significantly increased.

The second wave came a two to three decades later, after we had gotten railways and steamships.

Tired of Rome and Switzerland

“Many foreigners were tired of ancient Rome or the mountains in Switzerland,” the professor says.

It was often the English, Germans, and French who made the trip to Norway instead. While the tourists were treated to beautiful scenery, the availability of inns was poor, according to Rogan.

Again, it was the farmers who were responsible for taking care of the tourists. It was not just about providing transportation.

“The farmers themselves had to lodge lords, businessmen, and civil servant,” Rogan says.

Tourists slept in straw-filled beds, called flea boxes, or on a hard bench in a smoky living room.

They were served peasant fare such as trout, porridge, salted food, flatbread, and sour whey.

This applied whether the traveler was a lord or a duchess, professor or general, Norwegian or French.

Visits from educated people

If the English lords appreciated the Norwegian landscape, they were not impressed by Norwegian peasant food and straw bedding.

Tourists learned relatively quickly where better accommodations could be found. They then sought out the priest.

Socially, he stood far above ordinary people.

"[...] the official residences were like small islands in a sea of peasant culture," Rogan describes in a chapter in the unpublished commemorative volume Tid og historie (Time and history).

“The priests were overjoyed to receive visits from educated people. They were isolated out in the countryside, and months could pass between each time they saw strangers, and years between each time they had guests,” he says.

Knocked on the priest's door

According to Rogan, some travel guides in the middle of the 19th century even began to state that the parsonages were worth visiting.

“Avoid peasant beds, or flea boxes, and seek out the priest – he will welcome you. And they actually did so with great joy,” he says.

He further writes that a clever approach could be to knock on the priest's door and ask for the key to the church, as if the main interest was just to take a look inside.

It came down to a choice between flea boxes and down duvets. Eventually, the tourists became a burden for the priests; there were just too many of them.

Thought the mountains were ugly

The tourists came not long after Norwegians themselves had come to appreciate the qualities of Norwegian nature and landscape.

“The view of the landscape has changed quite dramatically,” Torild Gjesvik says. She is an associate professor of cultural history and museology at UiO.

Gjesvik has written both a doctoral dissertation on road motifs in art and the book Knud Knudsen - Veien, reisen og landscapet (Knud Knudsen – The road, the journey, and the landscape) about the photographer who travelled around and took pictures of Norway.

"If you go back a few hundred years, wild nature was considered ugly," Gjesvik says.

But in the 17th and 18th centuries, people began to admire the rugged nature.

In her book, Gjesvik has an example from Åsmund Olavsson Vinje. He was traveling in Rondane in 1860 and talked with locals about the nature and the mountains.

"With characteristic ambivalence, Vinje describes how his own attraction to Rondane meets steadfast resistance from the local farmers," Gjesvik writes in her book.

"You say that Rondane is beautiful, do you," a woman said to Vinje. "No, it’s as ugly as the devil himself," she is said to have countered.

Almost obsessed with the infrastructure

“The new roads that were built throughout the 19th century gave many more people access,” Gjesvik says.

This was especially true for artists who painted wild nature. New roads allowed them to access nature that would otherwise have been inaccessible.

"Even if the roads were not necessarily depicted in their paintings, it's known that the artists used the new roads on their study trips," Gjesvik says. "The artists also contributed to the general public becoming aware of traveling through the magnificent nature."

Learned from the English

It was the affluent Norwegians who were the first to explore their country as tourists, according to the book Turismens paradokser. Turisme som utvikling og innvikling (Tourism’s paradoxes. Tourism as development and complication).

The author is Arvid Ingmar Viken, professor of tourism at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. He has written the chapter on tourism throughout history together with Ola Sletvold.

"It started with upper-class people from Oslo being inspired by their English peers to go up into the mountains," the authors write.

Norwegians, on the other hand, did not catch the climbing bug.

They explored less extreme types of mountain sports.

They hiked in the mountains, climbed peaks, and from the 1860s began to trek from cabin to cabin, the authors say.

Most viewed

The English had often traveled to the Scottish Highlands or, as Rogan also mentions, to the Alps. There they engaged in mountain sports activities like mountain climbing.

In the beginning, affluent Norwegians received local help and training.

"The first mountain tourists made extensive use of mountain guides, preferably mountain farmers who were familiar with the areas."

Apparently, the mountain guides were both admired and criticised for being willing to lead the way in areas they knew, but less willing to venture into unknown terrain.

Cruises and cabins

Tourism in Norway has not just centred around mountains.

The first cruise ship to Norway is said to have left the dock in 1882, Sletvold and Viken write. The ship is said to have traveled from England to the fjords of Western Norway and then on to the North Cape.

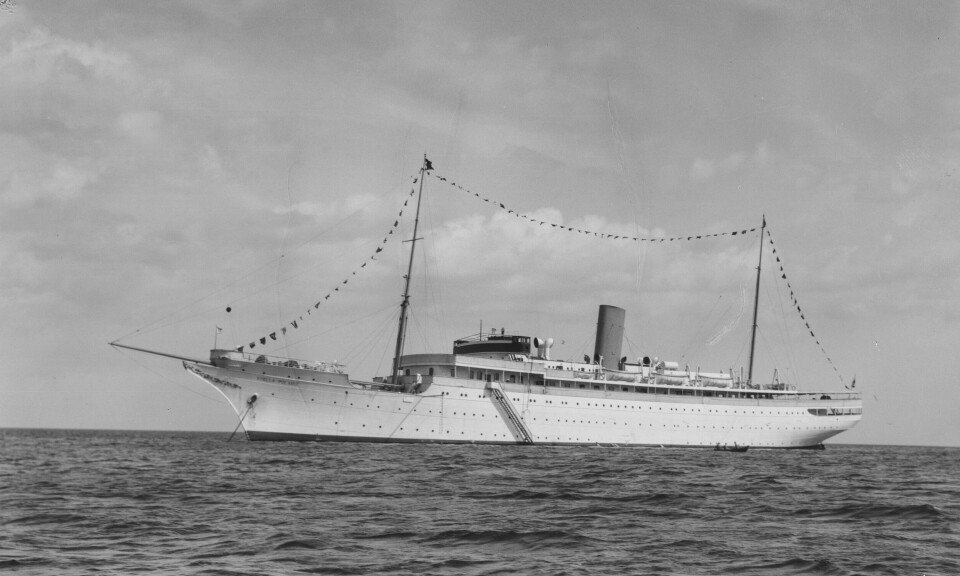

It wasn’t until 1926 that the world's first specially built cruise ship was launched.

The ship from Bergen Steamship Company was called MY Stella Polaris and sailed around the world, including along the Norwegian coast.

Maritime historian Bård Kolltveit described it as one of the most beautiful ships ever created, according to an article in the newspaper Bergens Tidende in 2020.

Odda was one of the towns transformed by cruise traffic.

32 tourist ships entered Odda in the summer of 1904, Torild Gjesvik writes in her book.

It went from being a small trading post on the west coast to becoming an important national tourist destination, she writes.

The growth in Norwegian cruise tourism was set to become even bigger.

In June, E24 (link in Norwegian) reported that Norway is on track to have nearly 3,400 cruise port calls by the end of the year. That's a new record.

Photos:

Tourists in horse-drawn carriages being transported between Odda and Låtefossen. The horses are waiting at Låtefossen. (Photo: Knud Knudsen / University of Bergen Library)

On the way to mountain climbing in Skjolden in Sogn. From right: Thorgeir Sulheim (owner of Eide farm seen in the background), Margaret Sophia Green, and Halvor Halvorsen. Green was a vicar's daughter from York in England who came to Norway to go mountain climbing. (Photo: Knud Knudsen / University of Bergen Library)

Hamlegrø Hotel near Bergen. (Photo: E. Grønberg)

Tourists with horse-drawn carriages in Stalheim. (Photo: Atelier KK / University of Bergen Library)

Carriage drivers by Vangsvatnet, with Fleischers Hotel in the background. (Photo: Severin Worm-Petersen / Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology)

Ships at the dock in Balholm in Sogn. (Photo: Atelier K. Knudsen / University of Bergen Library)

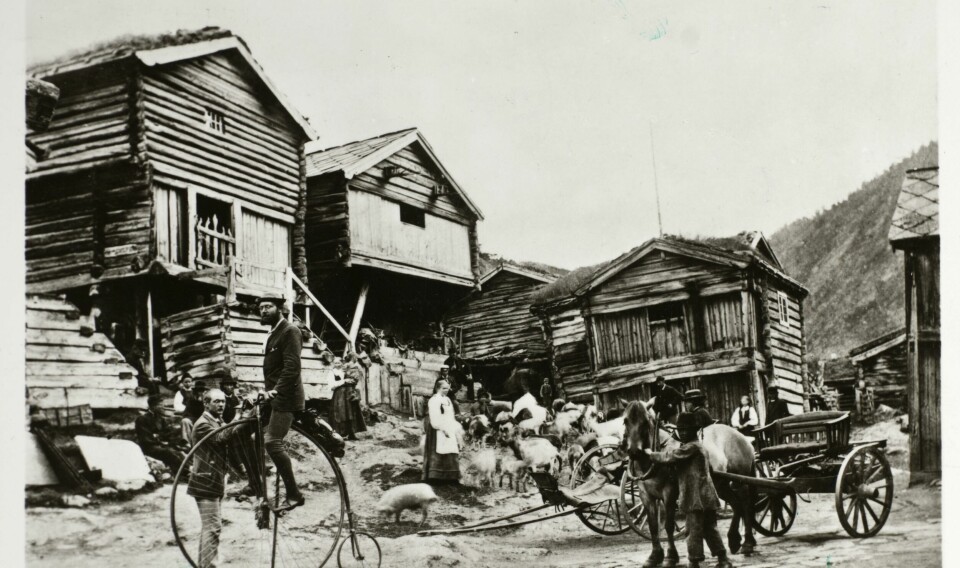

Man on a velocipede at Røisheim Hotel in 1885. (Photo: Axel Lindahl / University of Bergen Library)

Photo of a traditional wooden bench. (Photo: Stiftelsen Glomdalsmuseet)

Photo of flatbread baking. (Photo: Likely photographed by Lauritz Bekker Larsen / University of Bergen Library)

Tourists in Valdres. (Photo: Jens Embretsen Robøle / University of Bergen Library)

Låtefoss became a tourist attraction already in the 19th century. With Odda as the starting point, the first tourists went here. (Photo: Knud Knudsen / University of Bergen Library)

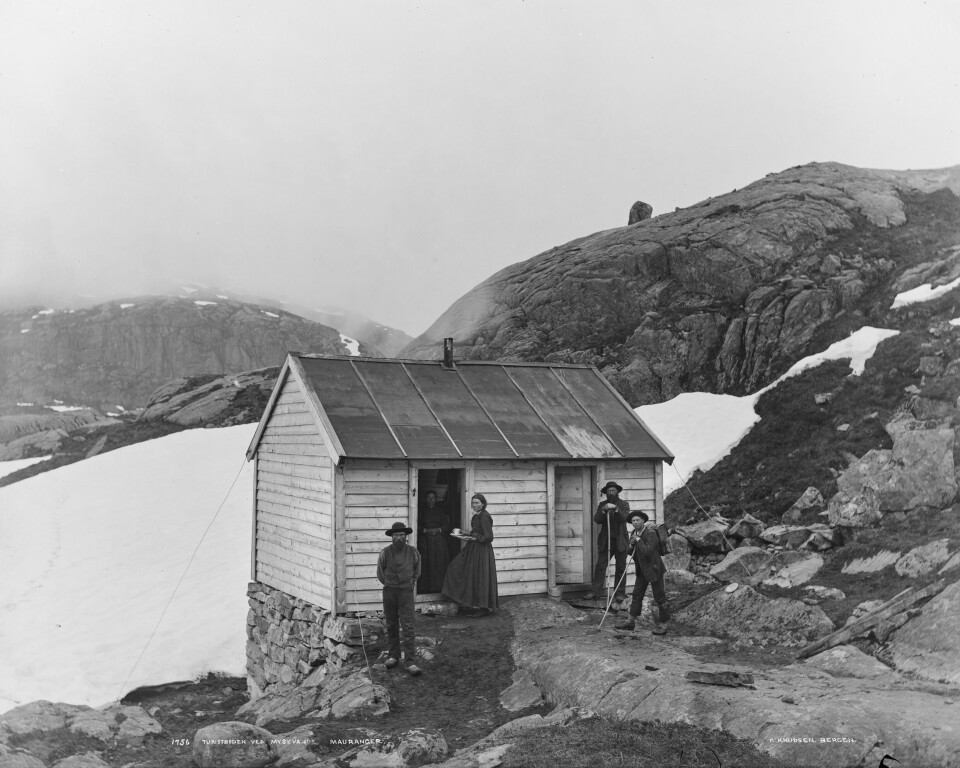

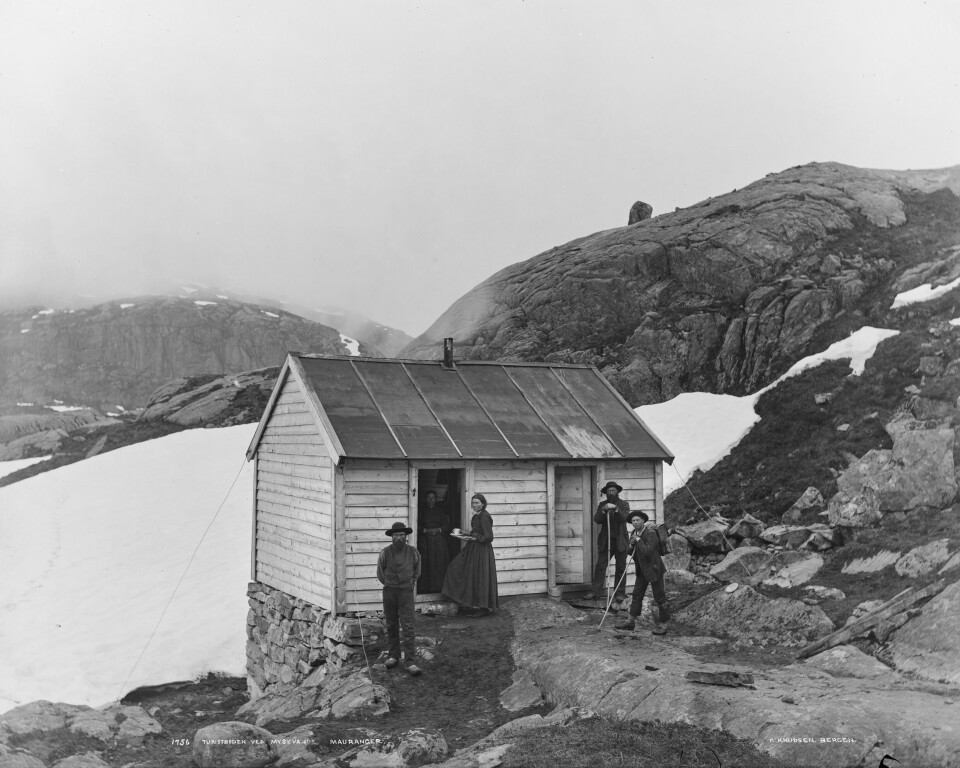

The tourist cabin by Mysevandet in Mauranger. (Photo: Knud Knudsen / University of Bergen Library)

MY Stella Polaris was the world's first ship built for cruising. (Photo: Atelier KK / University of Bergen Library)

Odda in the summer of 1904. (Photo: Jørgen Grundtvig-Olsen / University of Bergen Library)

References:

Gjesvik, T. (2018) ‘Fotograf Knud Knudsen: Veien, reisen og landskapet’ (Photographer Knud Knudsen: The Road, the Journey, and the Landscape), Oslo: Pax Publishing.

Rogan, B. (1998) ‘Mellom tradisjon og modernisering: Kapitler av 1800-tallets samferdselshistorie’ (Between tradition and modernisation: Chapters from the 19th century's transportation history), Oslo: Novus Publishing.

Viken, A. (2020) ‘Turismens paradokser. Turisme som utvikling og innvikling’ (Tourism’s paradoxes. Tourism as development and complication), Orkana Publishing.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no