Norwegian researchers start jihad archive

Jihadists’ propaganda and glossy magazines have now been assembled on a website to facilitate research.

“The enemy tank was destroyed and all the terrorists in it were killed,” reports the terror organisation Taliban in its magazine about an attack in Kandahar in Afghanistan in 2009.

The Taliban turns everything upside down from our perspective and calls the Canadian troops killed in their attack “the terrorists”.

The readers of “In Fight” see the war from the other side, with photos of caskets in a funeral and destroyed armoured vehicles.

The magazine is one of many sources gathered in the new Jihadi Document Repository.

Jihad, often translated as “holy war”, can be interpreted in many ways. Some of the warriors, mujahedin, battle to defend Islam. Others want to conquer new territory or spur domestic resistance in countries where Muslims are a minority.

“The texts stem from organisations like IS and al-Qaida, ideologists and grassroots initiatives,” says one of the persons behind the archive, Researcher Thomas Hegghammer at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI).

Jihad magazine in Norway in the 1980s

Most of the sources are in Arabic, but there are also English-language magazines aimed at a global public.

Some of these were distributed in Norway as far back as the 1980s.The “al-Jihad” magazine was distributed from an address in Oslo.

Hegghammer has not managed to find out who was behind it. He was surprised to see that the militant periodical had a Norwegian public. There was no organised operative circle of radical Muslims then, as compared to the Salafi-jihadist group that later arose in Norway, “Profetens Ummah”.

“But there was widespread support for the Afghan mujahedin in their war against the Soviet Union, also amongst Norwegian authorities. So a magazine about jihad in Afghanistan had a different ring to it than it would today,” he says.

Terrorists’ roots

FFI and the University of Oslo (UiO) have collaborated on the database. Their goal is to facilitate the work of researchers, students and others who are interested in analysing Islamic extremists.

FFI has a huge archive that is meticulously accumulated in the past couple of decades. Several FFI researchers have already worked with the material. Hegghammer is among them, as is Petter Nesser, who wrote his doctoral thesis on the roots of European jihadists.

As a start, about 2,000 of these documents will be available on the website. The idea is to spare new researchers from re-harvesting the same material as well as to enable others to evaluate the work done by FFI. Hegghammer hopes that other researchers will also contribute to research in this sphere by sharing their source material.

No videos

The archive consists mainly of material from the 1980s up to 2010. It covers just a microscopic part of the prodigious supply of jihadist propaganda out there, according to the FFI researcher.

Users will only find texts, none of the videos which sometimes combine professional production and spellbinding narratives to recruit new jihadists. With this omission the researchers are presenting just a narrow selection of the propaganda on the web.

They concentrate of central historical sources which are not so easy to obtain, especially magazines. Large collections of newer material are already available, for instance on jihadology.net.

The magazines are directed at a different public than the videos. The readers tend to be convinced Islamists who wish to delve deeper into the ideology.

“If the videos are the hashish of propaganda, the magazines are the hard drugs,” says Hegghammer.

Bin Laden’s mentor

The archive contains short biographies about key personalities, such as one of the terror organisation al-Qaida’s founders, Osama bin Laden. Some of his works are listed with links to the original texts.

Another central figure, Abdullah Azzam, is listed as the mentor of bin Laden. The Palestinian theologian has had enormous influence, including his notion that one hour of jihad is better than 70 years of prayer at home.

Azzam was killed by a car bomb in 1989 and several contemporary groups of fighters have named themselves after him. The Islamic State (IS) uses the names of al-Qaida’s fallen “heroes” on everything from schools for the children of foreign volunteer jihadists to groups of combatants.

Hegghammer thinks this is a good reason for studying the older propaganda.

“To comprehend what is happening today we need to understand the old groups. The new ones consider themselves to be follow-ups,” he says.

Dead ideologies still inspire

Hegghammer adds that these texts also continue to inspire new extremists.

One of Azzam’s texts in the archive is titled “A message to every youth”.

Two teenage girls from Bærum, just outside of Oslo, were inspired by the ideologist. The Norwegian-Somali sisters, aged 16 and 19, went Syria to join IS in 2013 and have not yet returned to Norway. They quoted Abdullah Azzam’s words to try and convince their father to approve. The author Åsne Seirstad describes their radicalisation in a new book “To søstre” [Two Sisters].

Home project

Organisations are not the only publishers of the material. Some of the websites are the products of individuals.

“These are people who want to contribute but cannot or will not engage in combat. Their ranks have grown, especially as internet participants,” says Thomas Hegghammer.

One example well-known example is Samir Khan, a young American-Pakistani who was killed in a drone attack in 2011.

He had gone to Yemen to assist in al-Qaida’s propaganda machinery. He helped publish “Inspire”, which has been savoured by jihadists in Western countries.

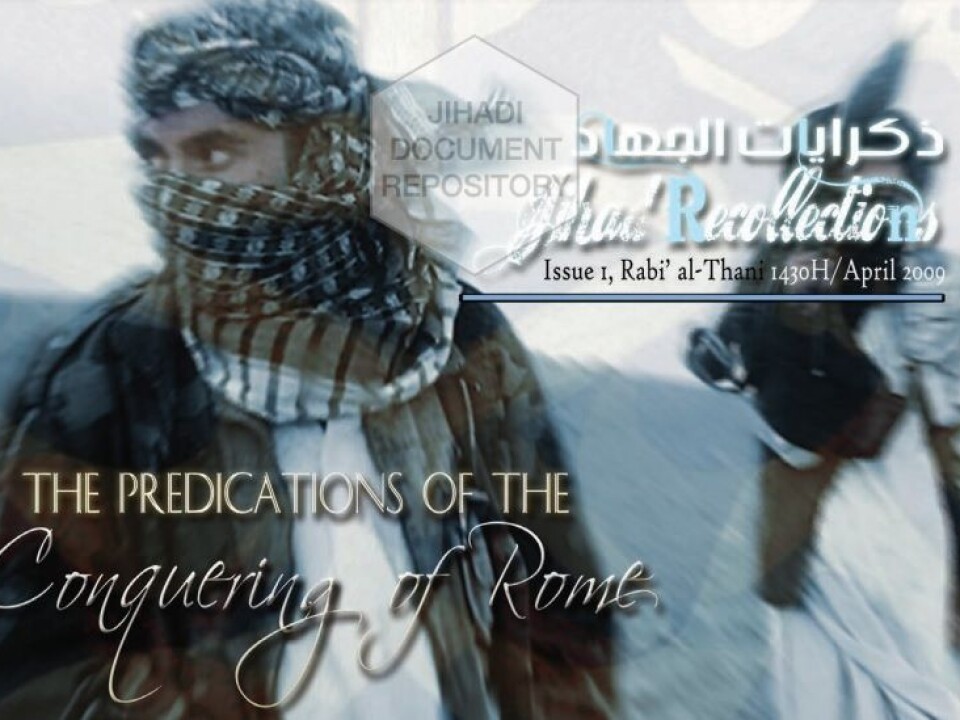

Much has happened since 2009 when he started what Hegghammer calls a boy’s basement or bedroom project, “Jihad Recollections”.

Column on fitness

The first edition of the magazine consists of sections on health, economy and social life.

Hegghammer explains that jihadists too are interested in miscellaneous reading material.

“This is a complex intellectual universe, with everything from films aimed at stirring emotions, via tabloid publications full of pictures and columns about exercising and nutrition, to heavy theological texts and political analyses,” says Hegghammer.

He thinks the aim of the columns on fitness is to help recipients get in shape to become foreign warriors.

It is not uncommon for totalitarian movements to offer lifestyle packages in their communications, explains Historian Øystein Sørensen, who has researched Nazi propaganda.

“The idea is to appeal to various sides of the recipient. The literature covers daily life problems while developing a correct ideological consciousness,” says the UiO professor.

Useful archive

Sørensen has also researched Islamic State propaganda, including the magazine Dabiq, which has been read in many countries and received much attention.

He thinks the new archive posted by the Norwegians is a good initiative.

“It can be timesaving when someone has already picked up something I would otherwise have to do loads of work searching for,” says Sørensen, with a reservation, as he has not yet viewed the fresh archive and thus not ascertained if it is something he can use in his research.

UiO Professor Tore Bjørgo, director of the Center for Research on Extremism, has already requested access to the archive.

He does not research militant Islamism, but thinks he can make use of the sources when studying radicalisation and extremism in general.

Fear of vulnerable persons being radicalised

The archive is currently password protected. In part to prevent abuse, all who want access need to apply. The Norwegian Defence fears that it could be used as a collected resource for jihadists. But Thomas Hegghammer would like to see it open for all.

On the other hand, Tore Bjørgo points out that even though the propaganda is already available on the internet, he is sceptical to opening it up to everyone. Like the Norwegian Defence, he fears that the researchers risk helping jihadists present a collection of their propaganda for target groups. Bjørgo would like to see the password protection retained.

“I think it would be problematic to let this material be accessible to vulnerable souls. The archive could then receive a whole new user group. That would include persons who might otherwise not have seen these texts, those who surf the web and are curious, but have not yet been radicalised,” he says.

He is glad that the archive does not include video material, which could help promote recruitments even more.

History Professor Øystein Sørensen disagrees about the necessity of guarding the repository by passwords to prevent it from having an unintended influence.

“This is an argument that can be used for all propaganda. Like the question of whether we should allow Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” to be freely sold. I think it is vital in our day to gain insights into how jihadists think and argue.”

Hegghammer argues that it is impossible in any case to make lasting safeguards against odious use of the material.

“We think that the learning we as a society gain from studying this archive has a greater impact in the fight against jihadist groups than any prospective inspiration it might have.”

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling