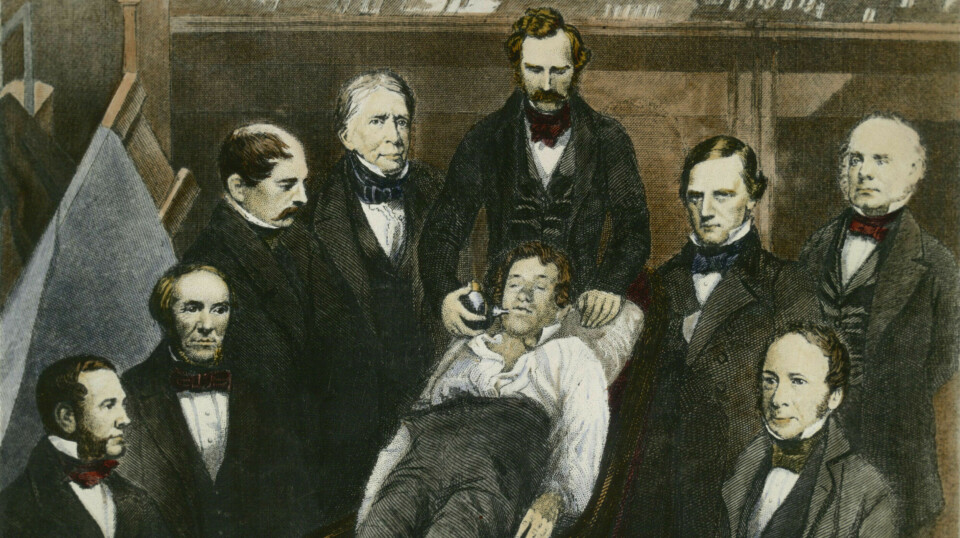

Boston 1846: William Morton demonstrates ether anaesthesia publicly for the first time.

But the road to today's painless surgeries was long and winding.

Researchers first had to survive nitrous oxide (laughing gas) parties, rivalries, and struggles for money and honour.

Patient safety and ethical standards weren’t part of the considerations.

The history of anaesthesiology is full of bitter conflicts and deadly experiments

In their eagerness for fame, doctors exposed their patients to mortal danger. Often, things ended tragically.

“I was amazed by all the life-threatening experiments that put the patient's health on the line,” anaesthesiologist Lars Prag Antonsen says.

Antonsen recently published the book Narkosens hemmeligheter. Alt anestesilegen burde fortalt deg før du sovnet (Anaesthesiology’s secrets. Everything the anaesthesiologist should have told you before you fell asleep).

Entertainment, addiction, and chance

The book was inspired by the questions Antonsen received from patients during his ten years as an anaesthesiologist. He is also working on a doctoral thesis on the topic.

“The goal of the early anaesthesiology pioneers was to develop techniques that made surgery painless for patients,” Antonsen says. "But the history of anaesthesia is also marked by drug addiction and comedic entertainment shows.”

And much was left to chance. Like when pest controllers made a mistake.

Most viewed

Survived amputation 12,000 years ago

The first surgical procedures were performed around 12,000 years ago – and perhaps even earlier. Skeletons with amputated limbs have been found, some with holes in their skull.

“We can see that the bone tissue has healed, so they survived. But we don’t know if or how these patients were sedated,” Antonsen says.

It is speculated that they might have used cooling and nerve compression, like when your leg gets numb after sitting cross-legged on the sofa for a while.

Suffocation is described in some places. The balance between unconsciousness and death is delicate. These methods were simple and primitive, and they did not require any equipment.

Knocked soldiers unconscious with clubs

During the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century, battlefield surgeons accompanied the army – or 'feldshers' as they were called at the time. They performed necessary amputations and operated to remove imbedded rifle bullets.

Napoleon's chief surgeon was Jean Larrey.

“Larrey knocked the wounded soldiers unconscious with a club. They were first given a leather helmet to prevent skull fractures,” Antonsen explains.

Considered the father of anaesthesia

The dentist William Morton is considered the father of anaesthesia. On 16 October 1846, he held a public demonstration in Boston, attended by numerous intrigued spectators.

The surgeon was to remove a tumour from the patient's throat after Morton had anaesthetised him with ether. The operation was successful. The patient felt nothing.

The news of painless surgery went around the world.

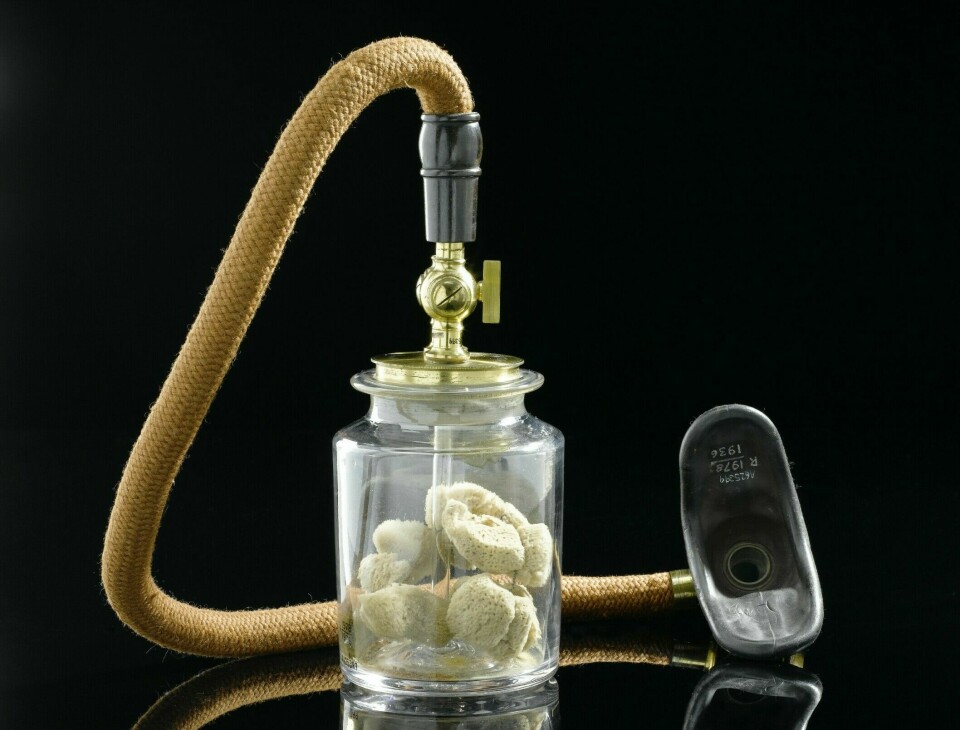

Morton’s demonstration is considered the beginning of anaesthesia. Already the following year, ether was used in surgeries at Oslo University Hospital in Norway. People were curious about what the anaesthetic contained.

“Morton tried to keep it a secret. He wanted to patent the invention, to achieve fame and become rich," Antonsen says.

He came from a poor background but was charismatic and had influential friends.

Never obtained a patent

The opposing camp believed that the substance should be made available to everyone.

Morton was a dentist and learned to use ether as an anaesthetic for tooth extractions. He later studied medicine.

Several other individuals claimed to have been the first to use ether as an anaesthetic.

Ether was by no means a new invention. It had been known for thousands of years that ether vapour could induce sleep.

Morton, however, risked his reputation by demonstrating its use publicly.

The event led to a bitter, years-long conflict. Morton ultimately received recognition and got the credit, but never obtained the patent.

Pinched the assistant’s testicles

But the truly crazy antics happened earlier. The American doctor Crawford Long anaesthetised his friend with ether at a party to remove a painful lump in his neck.

“Another doctor jabbed his assistant in the back with a spinal anaesthetic and pinched his testicles to see if it worked,” Antonsen says.

They put all ethics and patient safety aside and just went for it.

“And things also went wrong. Quite often the patient never woke up,” he says.

The doctors blamed it on the patient just being unlucky and not tolerating the anaesthesia, Antonsen says.

These risky experiments made valuable advancements, despite the high mortality rate.

Antonsen admits that it would probably have taken longer to achieve as much progress in the same time span, if it hadn’t been for the reckless individuals.

Magic potions

Magic potions have been used for millennia as anaesthetics. Herbs like mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) and henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) were used, often diluted in wine.

But the dosage was tricky.

The most famous literary example is perhaps Romeo and Juliet. Juliet is declared dead towards the end of the play, but she has merely been sedated by a monk with a poison potion. She wakes up to find that Romeo has taken his own life in despair.

Shakespeare probably wrote the play around 1590.

The opium poppy was cultivated as early as the Stone Age.

Ancient clay tablets and papyrus scrolls describe opium as a pain reliever.

“Many of today's anaesthetic drugs are synthetic relatives of opium,” Antonsen says.

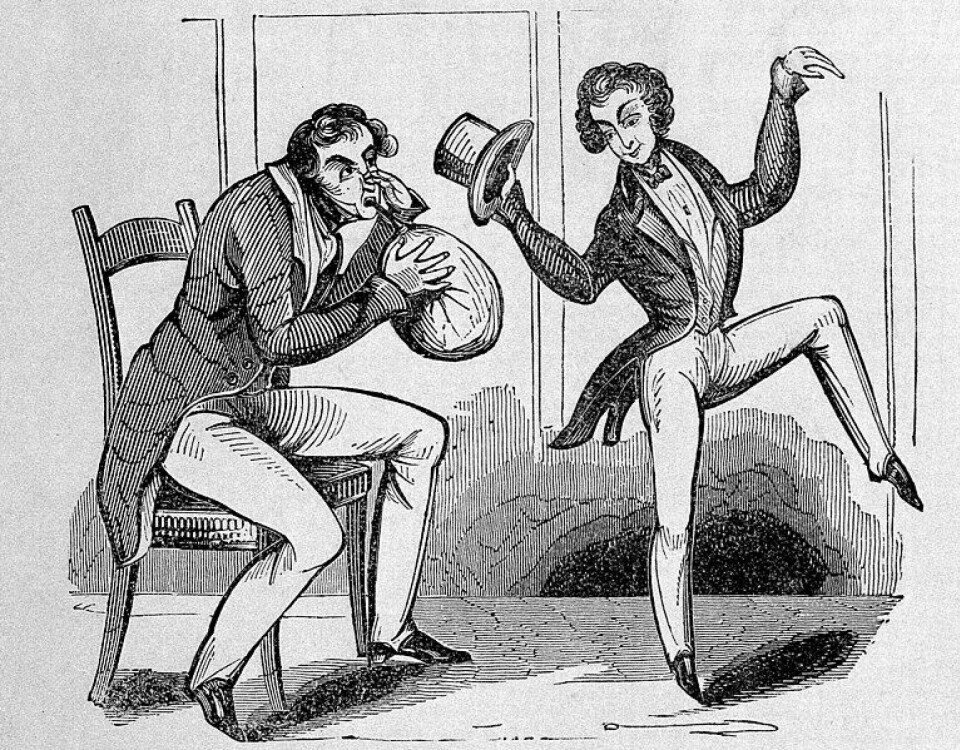

Laughing gas parties at the end of the 18th century

Humphrey Davy began using nitrous oxide in the late 18th century by chance.

“He described how he became euphoric from inhaling it. As an aside, he mentioned that it might be suitable for pain relief during surgical procedures. Davy became addicted to it,” Antonsen says.

During the 1790s, nitrous oxide, known as laughing gas, gained popularity among the cultural elite in Europe and the USA. Laughing gas parties became popular. Participants inhaled nitrous oxide from balloons and used it as a recreational drug.

Laughing gas performances were also arranged. Volunteers from the audience could come up on stage, inhale nitrous oxide, and engage in uninhibited behaviour.

“The spectators in the hall were entertained,” Antonsen says.

Dentist Horace Wells witnessed such a performance and noticed that the subjects bumped into things but felt nothing.

Patient screamed when the dose was too weak

The next day, Wells experimented on himself and had an assistant pull a tooth. He advertised nitrous oxide as an anaesthetic.

Wells wanted to demonstrate the anaesthetic at Harvard Medical School. However, his demonstration did not go very well. The patient screamed in pain when Wells pulled the tooth. The dose was too weak.

Horace Wells felt ridiculed as a scientist, fell into depression, and committed suicide under dramatic circumstances.

“Much of the reason was probably his damaged reputation,” Antonsen says.

Wells also felt betrayed by Morton, whom he believed had stolen his idea.

Nitrous oxide is now back in fashion. It is easy to buy cartridges over the counter and online. Young people transfer it to balloons and inhale it.

“However, it’s easy to become addicted to laughing gas, and it can cause serious neurological damage,” Antonsen says.

Ether is stronger than nitrous oxide and took over as an anaesthetic after Morton introduced it in 1846. Next came chloroform.

Substances against pests

Both ether and chloroform have dangerous side effects, and once again, coincidence played a role.

Around the time of World War II, people tried to find less flammable gases than ether.

A pest control company tried to develop a gas to kill beetles in grain silos. They thought they had killed them.

“But then the beetles started crawling out again,” Antonsen says.

That is when they realised that the substance only had an anaesthetic effect.

“The substance was eventually developed further into an anaesthetic gas called halothane. It was used for many years,” he says.

Stun arrows

Muscle relaxants are used in order to ensure that a patient lies completely still and the body's voluntary muscles don’t move during surgery.

The muscle relaxants originated in South America, where the Native American population used blowpipes to shoot anaesthetic arrows at their enemies.

These arrows paralysed muscles, including the diaphragm, causing the victim to suffocate.

“It wasn’t until the early 20th century that doctors figured out how to use this in a controlled manner, without the patients dying. Today, muscle relaxants, along with sleeping pills and painkillers, are an important part of modern anaesthesia.”

Awake during anaesthesia

There are many horror stories about people who have been conscious during anaesthesia, but were unable to indicate that they could feel the knife cutting them.

“There’s actually a theoretical possibility that you could give a patient a normal dose of muscle relaxants, but not enough sleeping medications or painkillers. That’s where the horror stories originate of patients who wake up but are completely paralysed and unable to speak or give any signs of distress,” Antonsen says.

This situation is called anaesthesia awareness and is a feared condition for anaesthesiologists and patients alike. Fortunately, it is extremely rare.

“When someone remembers details from falling asleep or waking up, the operation is over. It feels like a dream and is completely harmless," he says.

Scepticism and progress

The development of anaesthesia had two sides. On the one hand, there were a bunch of non-traditional characters who just dove in, without thinking about safety, Antonsen explains.

“They were motivated by the prospect of achieving honour and fame – and money,” he says.

On the other side were conscientious scientists who believed that anaesthesia had to be developed gradually, Antonsen explains.

“Experiments like these can perhaps be called research, by virtue of trying out something new. But accountability and ethical rules about not putting health and human life at risk came much later,” Antonsen says.

The rise of patient safety

“One of the fundamental issues at the start was the lack of any system to register side effects. A lot of patients died. Doctors thought it was because patients just couldn't ‘tolerate’ the anaesthetia,” Antonsen says.

Doctors eventually developed techniques to monitor a patient’s breathing, pulse, and blood pressure.

After World War II, people like Robert MacIntosh and Henry Beecher began to record complications. That’s when patient safety found the place it holds today, Antonsen notes.

“They contributed to elevating the field of anaesthesia from being a mythical, dangerous craft to a modern, safe medical speciality,” he says.

Greater emphasis was placed on monitoring patients, educating doctors, and spreading knowledge.

More local anaesthesia

In recent years, new medications that quickly leave the body have been developed.

“Personalised dosing is the new trend. And artificial intelligence can analyse possible complications in real time,” Antonsen says.

These new measures provide safer anaesthesia.

In recent years, operating without putting the patient under general anaesthesia has become more common, and more local anaesthetics are used.

An epidural that can be used during labour is a typical local anaesthetic. Or you can anaesthetise just an arm or a leg and operate on it.

Reference:

Antonsen, L.P. 'Narkosens hemmeligheter. Alt anestesilegen burde fortalt deg før du sovnet' (Anaesthesiology’s secrets. Everything the anaesthesiologist should have told you before you fell asleep), Spartacus Forlag, 2023.

Image at top:

William Morton's first demonstration of ether anaesthesia occurred during the extraction of a tooth at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston on 30 September 1846. (Photo: akg-images/NTB, coloured afterwards)

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse