Born late in the year? Then it's much more likely that you will pursue a vocational track

Norwegian researchers have found a strong correlation between our birth month and the educational choices we make.

If you are a girl and born early in the year, you will most likely choose an academic educational track in upper secondary school.

If you are a boy and born late in the year, you will likely pursue a more trade-oriented vocational track in upper secondary school.

The effect of when in the year you were born is greatest for boys.

Explained by maturity level

“There’s no logical explanation why pupils born in the latter part of the year are more interested in vocational subjects than those born early in the year.”

“We believe that this has to be explained by differences in age and maturity, as well as the opportunities and follow-up that pupils receive in school,” says Kari Elisabeth Bachmann.

Bachmann is a professor of pedagogy at Volda University College and Kristiania University College and one of the authors behind a recently published study.

The researchers used data from close to 30 000 upper secondary school students in Møre og Romsdal county municipality that extends over eight years.

“We have no reason to believe that this county stands out from other counties in Norway,” says Bachmann.

The researchers therefore believe that the trend is the same across all Norwegian counties.

Recognized by teachers

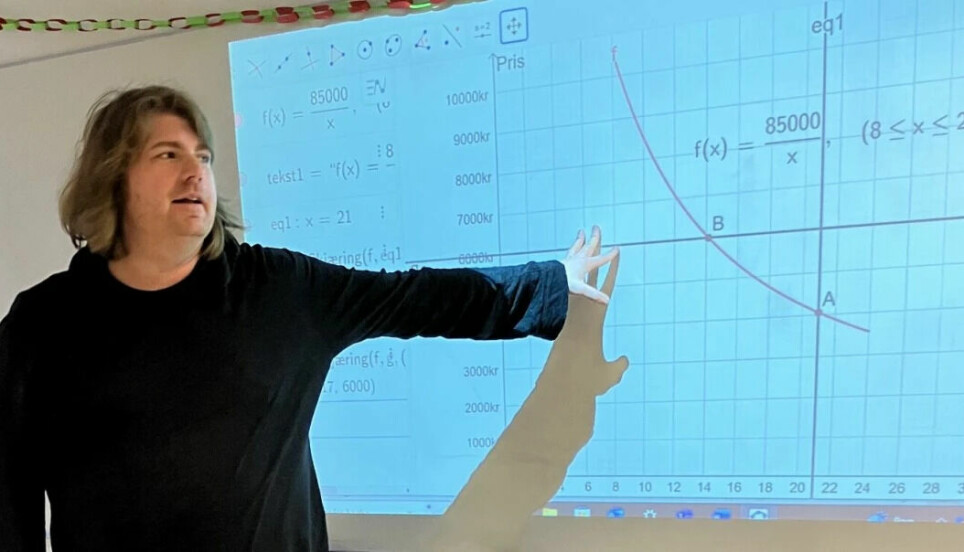

Espen Grøstad has been a secondary school teacher for 19 years.

He is well aware that maturity levels can differ in a class between the first and last pupils born in a given year.

“We also often see big gender differences. The difference between a boy born in November or December and a girl born in January can be quite large in secondary school.”

But he believes it’s not always a given that teachers observe students doing well or poorly based on when they were born.

“It’s not like all is lost if you were born late in the year. A lot depends on a pupils's own effort and attitude toward school. And the follow-up at home also matters,” Grøstad says.

Worse grades

Several previous studies have shown that children born early in the year do better academically at school than children born late in the year.

In 2019, the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training presented an analysis that indicated the same. It also showed that the month of birth can influence the choice of upper secondary school, according to a Norwegian article in Aftenposten.

The new study from Møre og Romsdal now confirms the same findings.

Known within competitive sports

Researchers have conducted numerous studies on relative age effects in sports – that is, the differences within cohorts that arise from the month of birth.

Geir Oterhals teaches sports management at Molde University College and is the first author of a new study.

“Those responsible for selecting athletes for elite teams tend to choose players who were born early in the year.”

The question arose in a discussion Oterhals had with the students about the relative age effect. A student who had been a substitute teacher for a vocational course of study thought that the pupils there most often had birthdays late in the year.

That's how he and several research colleagues had the idea to investigate the topic further.

Link found internationally

In countries such as Germany and Austria, researchers have also discovered this correlation. However, these are countries where young people have to make educational choices much earlier than here in Norway, says Oterhals.

“You might imagine that these differences would disappear by puberty and that when 15–16 year olds have to choose an educational track, the month of birth would no longer play that much of a role.”

But that is not the case.

The researchers found clear effects related to pupils’ month of birth and choice of educational direction in Norway as well.

Self-fulfilling prophecy?

The researchers believe this finding indicates that not all students experience the same supportive conditions for their development in school.

The researchers do not know the marks received by the students included in the study. But other studies have shown that, on average, especially boys born late in the year have worse grades than other students.

“So then they have to choose a study programme they can get accepted into or think they can do well in, and not necessarily what they’re most interested in,” says Oterhals.

But this can go both ways, he believes.

“It can also be the case that girls who are born early in the year and have good grades, opt for the most difficult and prestigious study programme, which might not be what they’re most interested in either.”

Negative spiral

Kari Elisabeth Bachmann fears that what might start as a different maturity level between a January child and a December child can eventually create a negative spiral.

When children born late in the year start being tested at school, they may find that they do worse than the oldest children in the class.

When children born late in the year start being tested at school, they may find that they do worse than the oldest children in the class. That can affect their self-image.

“That can affect their self-image, and feeling that they’re not good at school may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

It could also be that teachers give more support and encouragement to the pupils they expect will perform best, which can affect the self-image of the brightest students. They might gain greater academic self-confidence.

One not better than the other

Bachmann and Oterhals point out that they are not saying that an academic course of study is better than a vocational course of study.

They also point out that there are big variations in how difficult it is to get into different vocational programmes. The result might have been different if pupils had looked at the individual subjects separately.

“We just observed how the students sorted themselves out between the academic study tracks and occupational trades when these two main directions were studied together.”

This sorting showed itself to be influenced by what time of the year a student was born in. And it affects boys the most, says Bachmann.

The boys are impacted by a double effect.

When children start school, boys are generally somewhat behind girls of the same age in their development.

When they then also compare themselves to the oldest girl in the class, the gap becomes even wider.

What is the solution?

The researchers' results do not inform us about each individual pupil. Rather, they tell us something about a large group of students.

A boy born in December could also turn out to be the most mature student in the class.

Bachmann believes the solution does not lie at an individual level, such as postponing the start of school.

“These are completely normal children who are developing normally for their age. They’re placed in a class where some of their peers are as much as a year older. Although a delayed school start can work well for some, large variations between the students in a class will still exist.”

In an inclusive school, students are diverse. Trying to sort the students into a homogenous group may not be desirable or possible, she believes.

More ADHD among youngest

PhD candidate and paediatrician Christine Strand Bachmann has recently published an article in which she presented a link between the time of year Norwegian children are born and how often they are medicated for ADHD.

You can read more on this topic in this viewpoint article.

“We concluded that increased medicating of the youngest members of the class is related to how we organize our educational system. It might look like we medicate the youngest children because of their immature behaviour in class, even though their behaviour is perfectly normal for their age.

She believes that the same issue could be influencing pupils’ choice of study track.

“We see little evidence that children born late in the year would have both more ADHD and would more often choose vocational subjects. That leaves us with the difference in maturity as a plausible explanation.”

Research has shown relative age effects in many areas, says Strand Bachmann.

“Studies have shown that people born late in the year have poorer self-esteem. It has also been shown that they tend to experience less strong friendships and less satisfaction in life,” she says.

Delayed school start can be helpful

It is quite clear that this issue requires more attention, says Strand Bachmann. She thinks delaying the start of school could be one of the solutions.

Delaying a child’s start of school is relatively uncommon in Norway and many other countries.

That is not the case in Denmark, where as many as 40 per cent of children born between October and December postpone their school start, says Strand Bachmann.

“Interestingly, the finding from Danish studies that have looked at ADHD medication are not the same as in Norway. The youngest children are not more highly medicated there. This could indicate that postponing the start of school actually has a positive effect.”

Potential long-term consequences

The solution probably lies more in addressing how schools can provide all pupils with better conditions for learning and development, says Kari Elisabeth Bachmann.

It is very important to increase teachers' awareness of the impact of differences in age and maturity level.

“We think it’s essential to increase teachers' awareness of the importance of recognizing disparities in age and maturation.”

Having an understanding of relative age effect can contribute to teachers paying more attention to the fact that differences between pupils can involve age and maturation, and not just how good a pupil an individual child is.

“There’s no simple solution to this. How teachers can better adapt the instruction based on the students' prerequisites, interests and needs will play a major role,” Bachmann says.

She finds the discussion about Norway’s six-year reform, implemented in 1997, and the transition between kindergarten and school to be interesting and important in this context.

The researchers believe that school administrators and school policymakers should also be aware of these research findings and what they could mean for working to facilitate equal education.

They remind us that the choice of a course of study can have a far-reaching impact for a student's career prospects.

Not looking at the calendar

“As a teacher, I have a duty to adapt the training so that it’s effective,” says Grøstad.

“We don't go into the calendar and check when our pupils’ birthdays are. We generally look at which students need something extra.”

He believes this is an important point.

“If you start struggling to be successful in school, the snowball starts to roll and leads you to lose your motivation. And vice versa. If you notice that you’re successful, it’s easier to stay motivated for your school work.”

Something has happened

Grøstad points out that something has happened in how students are distributed in academic and vocational educational tracks in recent years.

“Vocational subjects have become much more ‘talked up’ than they were 15–20 years ago, and this has had an effect on the number of people applying to those programmes,” he says.

“In the past, it was often students who weren’t succeeding in academic subjects who chose to pursue vocational studies. Today, more academically strong students are also choosing this educational track. We’ve had years in which the entry requirements have been higher to get into the electronics course of study than into academic study specialities,” he says.

Reference:

Geir Oterhals et.al.: The relative age effect shifts students' choice of educational track even within a school system promoting equal opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 2023.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no