Why do jellyfish sting?

"The ability to sting is not something the jellyfish controls itself," says researcher.

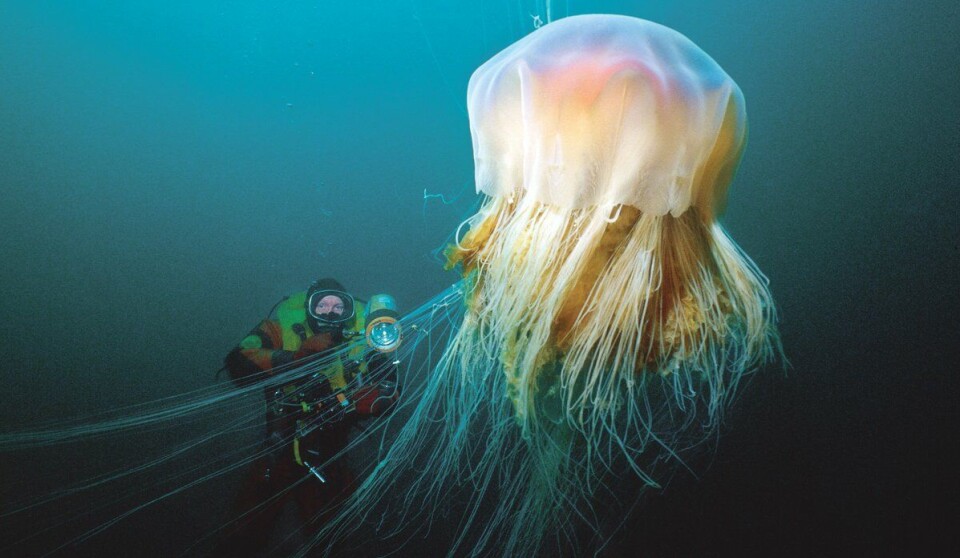

If you're planning to swim in the ocean in Norway this summer, keep an eye out for both lion's mane jellyfish and blue jellyfish.

The tentacles that hang from these jelly-like creatures will sting you if you touch them.

But what causes that painful sting?

Jellyfish sting for two reasons, says researcher Tone Falkenhaug.

Attack and defence

First, they sting to catch food.

"Jellyfish don't have claws or teeth, so their weapon is a toxin that paralyses their prey," says Falkenhaug.

They feed on small creatures like copepods, fish larvae, and even smaller jellyfish.

The second reason? To protect themselves from predators.

Birds and fish both consider jellyfish a tasty snack.

A secret weapon

So what actually happens when a jellyfish stings?

The answer lies in some very special cells.

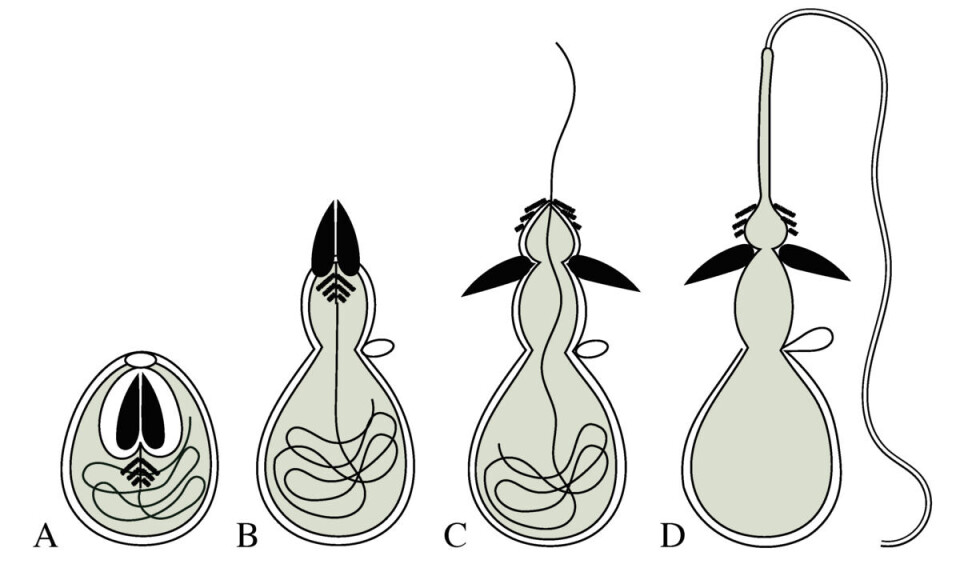

"Jellyfish have long tentacles lined with densely packed stinging cells called cnidocytes," explains Falkenhaug.

As long as nothing disturbs the jellyfish, the tentacles are completely harmless.

But inside each cnidocyte is a hidden weapon.

"Fires out at incredible speed"

Coiled up inside the cells is something Falkenhaug compares to a harpoon – a tiny spear connected to a thread.

Most viewed

Inside the cnidocytes, there is also enormous pressure, kind of like a soda bottle that has been shaken vigorously.

"When a small animal brushes against the tentacle, the cell bursts, and the harpoon fires out at incredible speed and force," says Falkenhaug.

The harpoon delivers a dose of toxin that paralyses the prey.

This allows the jellyfish to eat the prey in peace, through the mouth located in the middle on the underside of its body.

No interest in humans

The same reaction happens when we touch jellyfish in the water.

"The harpoons fire automatically, releasing the toxin, and it really stings," says Falkenhaug.

But jellyfish have no interest in us humans, she adds.

"The ability to sting is not something the jellyfish controls itself," she says.

Even the moon jelly stings

Even though their sting is painful, jellyfish in Norway are not considered dangerous.

If you get stung all over your body by a lion's mane jellyfish or blue jellyfish, you will probably feel quite ill afterwards.

But unless you're allergic, it's not dangerous, according to Falkenhaug.

She also reveals something surprising about another familiar species.

The moon jelly can also sting.

"For moon jellies, their sting and toxin are so weak that they usually don't penetrate the skin on our hands," she explains. "But if you were to place them on your lips or eyelid, you'd probably feel it."

Help the researchers this summer

This summer, Falkenhaug and other researchers at the Institute of Marine Research would like your help.

Have you seen an unusual jellyfish? Or a lot of jellyfish in one place?

Report your findings at Marine Citizen Science.

There, you can also check what others have seen.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

References:

Britannica: Cnidarian

Institute of Marine Research: Stinging jellyfish

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.