Were Norwegian whalers worried about what they were doing?

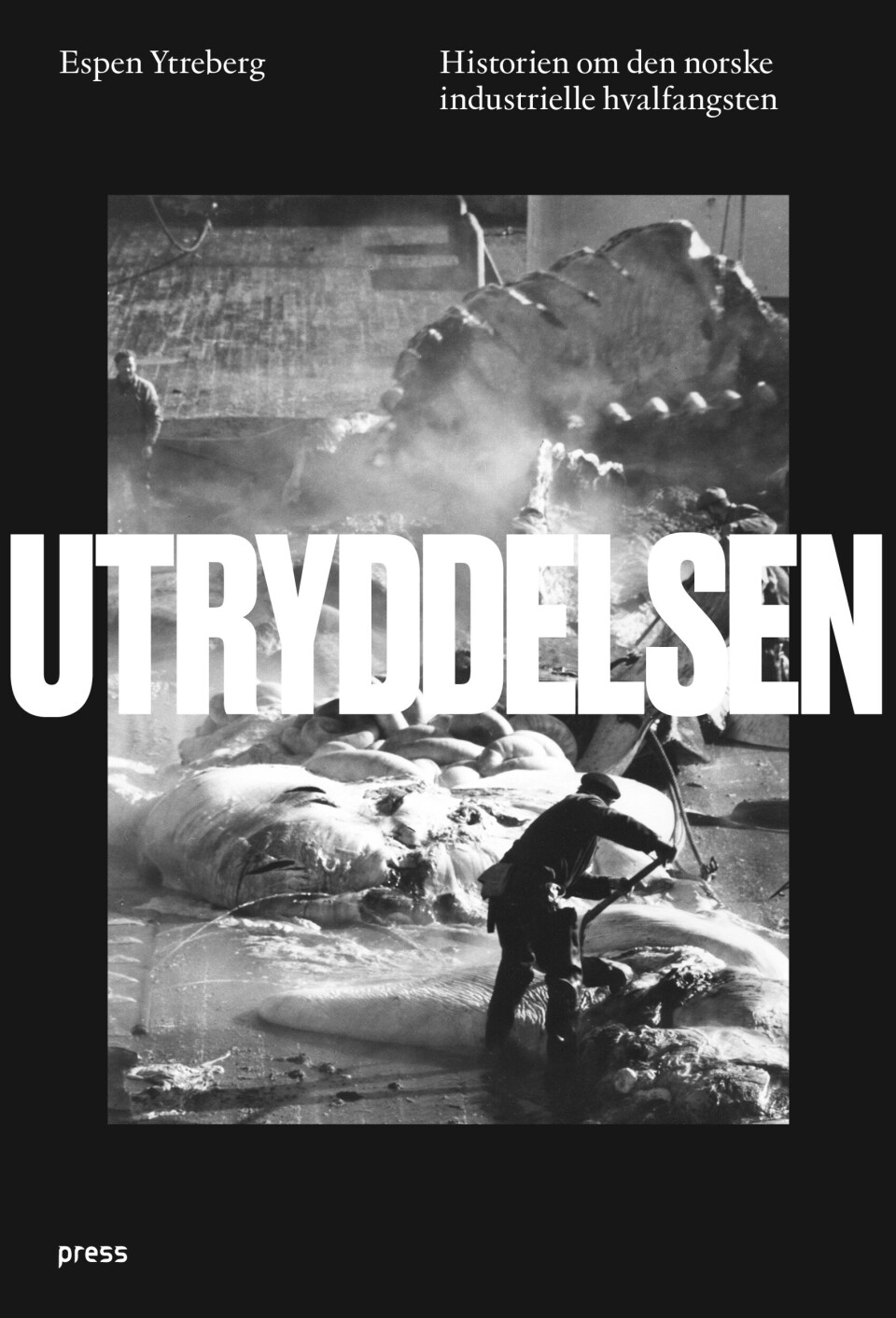

Norwegian whaling in the Antarctic consisted of blood, toil and adventure. In his new book, Espen Ytreberg writes about daily life in the industry that ended up almost wiping out the big whales.

You are standing outside on a huge boat in Antarctica. An enormous blue whale lies on the deck, in the process of being flensed and split.

Men operate winches to move the leviathan, while commands are shouted through the noise and icy wind. Workers cut blubber with long knives, while others have the task of climbing halfway into the whale and sawing it into pieces by hand.

The stench from entrails and meat is pervasive. Blood, fat and fluids pour out of the carcass, making everything slippery, while heavy chains and cranes fly overhead.

“It was an extremely demanding and at times very dangerous working environment, with tremendous sensory overload,” says Professor Espen Ytreberg.

“All the work had to be done in an environment that was completely permeated with whale flesh, gunk, blood and stench,” he said.

Photographs and diaries

In his new book, ‘Utryddelsen’ (the Extinction), Espen Ytreberg, a media historian and professor at the University of Oslo, takes the reader up close to the realities of Norwegian whaling. Based on photographs and stories from whalers themselves, he has written about a chapter of Norwegian history that many Norwegians might rather forget.

“The photographs allow you to get close to the kind of sensory experiences people had while whaling,” Ytreberg said.

“I think that’s very valuable. You get a sense of how unique and in many ways extreme the experience was,” Ytreberg said to sciencenorway.no.

This particular story did not end well. When the capture of the great whales finally ended in the 1960s, the humpback whale, the blue whale and the fin whale were practically eradicated from the world's oceans.

The most powerful animals on the planet had been turned into margarine and soap that had long since been used up.

“The extinction began in our own waters,” Ytreberg said.

Started outside Finnmark

Whaling has been going on for centuries, but what historians call industrial whaling began in the 1860s.

Svend Foyn, a Norwegian sealer from Tønsberg, invented the harpoon gun and grenade harpoon, both of which were more effective weapons than conventional harpoons. The grenade harpoon exploded inside the whale.

Coupled with newly developed steam-powered whaleboats, it became possible to go after larger and faster whale species, such as fin whales and blue whales. Shipowners from Vestfold went to Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost county, and developed industrial whaling.

The new methods soon eliminated most of the whales in the waters off northern Norway.

“Some people quickly began to worry that the whales were threatened with extinction,” Ytreberg said.

Onward to distant regions

Norway passed a law in 1904 that banned whaling in northern Norway. By then, shipowners had already sent their fleets south, to new hunting grounds.

The intention was to travel far, to the opposite end of the globe, to the world's most desolate and inhospitable place. They went to the seas around Antarctica.

Before this, Norwegians caught whales for a time around places like Svalbard and Iceland, Ytreberg said. But the whalers had heard that that the really large populations of whales were to be found in the south.

It was true.

Gold rush vibe

This southern expansion happened quickly.

“This gave Norway a leading role in industrial whaling in the south. We not only exported industrialization globally, but also the issue of extinction, very quickly,” Ytreberg said.

The first land station was established on South Georgia island in 1904. Land stations sprang up on small islands in the seas around Antarctica.

Whales were brought here to be slaughtered and boiled to extract the coveted whale oil. The process could also be done on ships, on floating whale cookeries. There was a flurry of activity. Whalers came from many nations, but Norway led the way for a long time.

“I have compared it to what happened in the Klondike at the same time,” Ytreberg said.

However, the hunt had its dark sides, which came to affect the industry in certain ways.

Ytreberg’s book describes what happened on Deception Island, a deserted island in Antarctica. This was one of the islands where Norwegian whalers dominated.

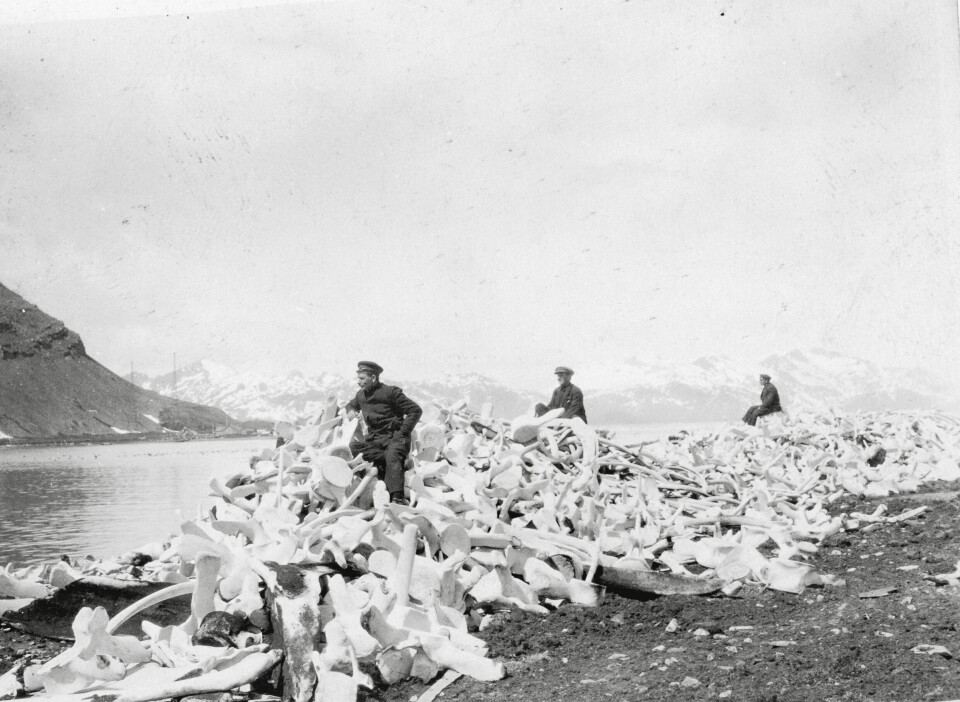

Piles of carcasses

The horseshoe-shaped island had an inner lagoon. Here there were floating cookers and a land station. Whales were brought here to be processed.

However, it didn’t take long before conditions became dire. When there were a lot of whales and good prices, it paid to just cut the outer blubber off the whale and dump the rest. The outermost layer contained the most accessible and valuable oil.

As a result, mountains of skinned whales were left on the beach to rot. In the summer, whale flesh floated out of the water in the lagoon. The smell was described in the reports Ytreberg reviewed, with words such as suffocating, poisonous, enveloping and invasive.

"It was as if a sea of water bordered another, more viscous sea made of whale remains, with the whale carcasses themselves as stinking islands," Ytreberg wrote in his book.

In 1912, eight years after whaling started on the island, 6,000 carcasses could be counted on a few kilometres of beach.

Couldn't get completely clean

The whalers systematically dumped carcases on a large scale during this early part of the industrial age, especially when there was great demand for whale oil, Ytreberg said.

Later, the practice of discarding animal parts was reduced, but never disappeared, he said.

“There were initial reports that the dumping continued, but more secretly. Basically, it was nearly impossible to prevent a lot of the animal from being wasted when the whale was dismembered,” he said.

It’s impossible to establish clean zones when a giant whale is being slaughtered, unlike in indoor slaughterhouses, where animals are suspended and moved by conveyor belts.

“It wasn't until pieces of the whale were cut up, put in the kettle and steamed that the animal was disinfected,” he said.

Everything took place outdoors. Offal and bodily fluids leaked from the animals and covered the surroundings.

Ytreberg’s book describes how the workers' daily lives were saturated in whale offal. The stench settled in clothes, common areas and bunks. Whale blubber dissolved in steam left a sticky film on everything.

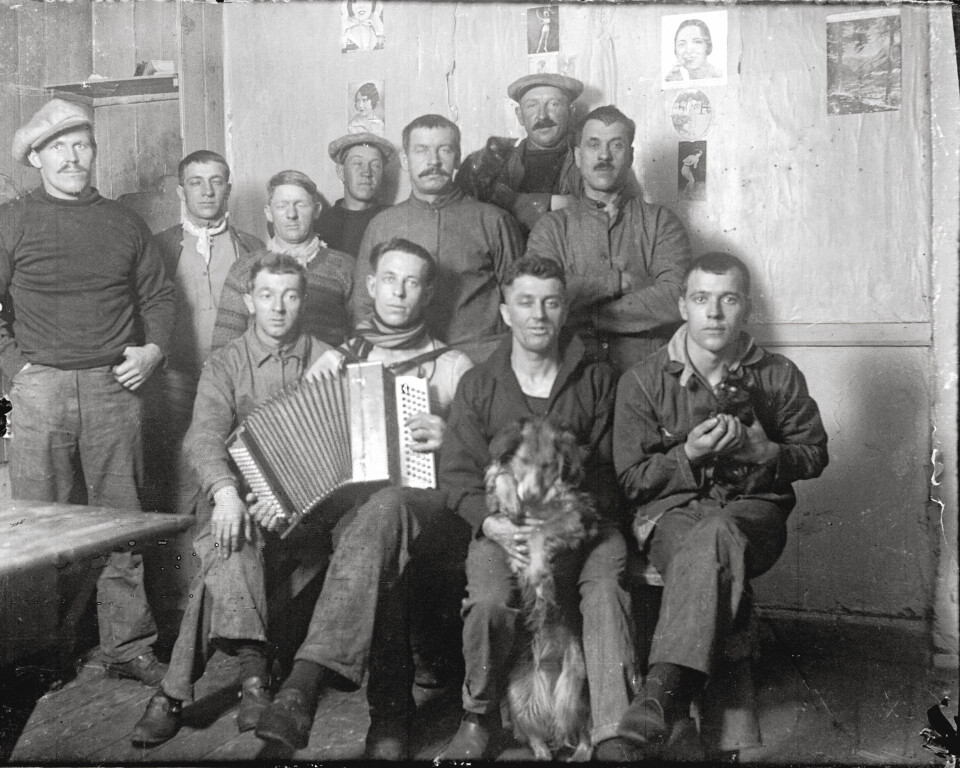

Strong cohesion

The whalers had different views on what it was like to live and work in this demanding environment near Antarctica.

Some whalers described whaling as something positive in their lives, Ytreberg said.

“Others talked about it as a struggle and a burden that came to affect them,” he said.

One recurring theme was the strong bond between the men.

“I compare it to accounts from soldiers who have been at war. They also talked about the importance of cohesion,” he said.

Ytreberg thinks this is due in part because the whalers lived so closely together, in small cabins and cramped barracks.

“They had to work in teams that had to cooperate closely to get the job done and be safe. You always had the risk that it could be dramatic, that it could be fatal. It contributed to the feeling of a shared destiny,” he said.

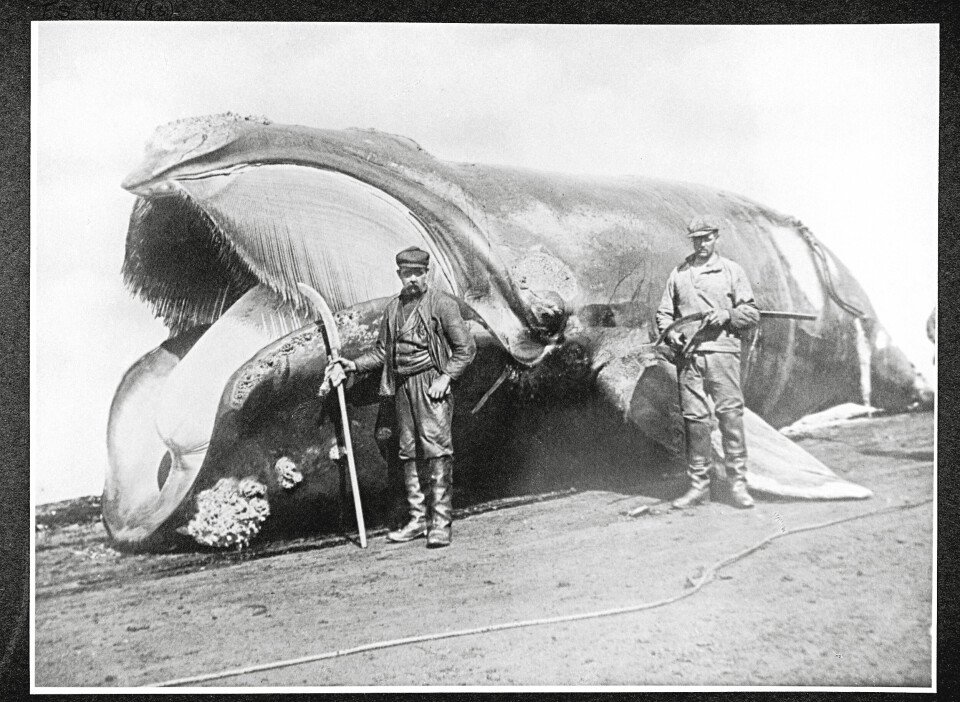

Conquerors

Among the subjects in the photographs are men standing on whales or putting their feet on whales.

This is a genre that is linked to modern outdoor life, with hunting as a sport and leisure activity, and to the motif of man as the conqueror.

The early whaling period was also the period during which heroes were explorers, such as Nansen and Amundsen, Ytreberg said.

“They like to stand by the planted flag and show off the moment of conquest. I think it's akin to these whaling pictures, where you mount the big whale, so to speak, and are visually portrayed as the conqueror,” he said.

The motifs also relate to the idea of whaling as an adventure.

“It could be an adventure in itself to travel to the opposite end of the globe or witness the catch itself,” he said.

At the same time, not everything about everyday life was exciting. It was hard work.

“This was industrial work. Much of it was repetitive and required a great deal of discipline,” Ytreberg said.

Another recurring motif in the pictures was the harpooner, with a whale in his sights. The harpooner became popular and was almost like a celebrity of the time, Ytreberg said. These photographs represented the decisive moment.

“I think this moment of excitement is the natural opposite of the repetitive, machine-dictated life,” Ytreberg said.

If the whale could scream

Were whalers concerned about the ethics of what they were doing?

Ytreberg said the majority never wrote about this issue in their reports.

“In the books that were written long afterwards, you can find some whalers who are strongly critical of themselves and the profession. It’s notable that they are characterized by the fact that they now live in a time where the environment has a different status and where whaling has a worse reputation,” he said.

Some had concerns, while the catch was going on, about extinction or that too many whales were being harvested.

What was perhaps more common was concern for animal welfare.

“Seeing a whale suffering and bleeding, sometimes for hour after hour, made an impression on some of them,” he said.

With a good shot, a whale could die quickly. Other times its death was prolonged. It made an even deeper impression if the whale had an offspring by its side or if other whales followed and apparently showed compassion, Ytreberg wrote in his book.

"If the whale could scream, the Arctic Ocean would become hell for us," one of the whalers wrote.

Blood on their hands

For a long time Norwegians led the way in the catch, which probably ended up being "the most extensive destruction of biomass that humans have ever caused," Ytreberg wrote in his book.

Despite that, whaling has not been a central part of Norwegians' historical consciousness, he points out.

Bjørn Lorens Basberg is professor emeritus of economic history at the Norwegian School of Economics and is an expert on whaling history.

He has read Ytreberg's manuscript as a consultant for the publisher, but not the published edition as yet.

Basberg says that Ytreberg has a different perspective on whaling history, by basing his approach on is the historical photographs. Business history often involves taking other perspectives, such as economics.

“It’s good. It provides a new angle, and is a welcome contrast to what has been written about whaling in the past, which has mostly taken a less bloody angle,” Basberg said.

Basberg thinks the book may have become a bit gory at times.

“But Ytreberg has obviously highlighted an under-communicated perspective, even though this aspect of the catch has of course always been known and pictures have been published,” he said.

Whales were hunted in times past, too

How big was Norway in whaling compared to other nations?

Basberg notes that whaling has a long history.

“In the 19th century there was a large global whaling industry, with the Americans leading the way. Before that, in the 18th century, the English, Dutch and French caught a lot of whales in the Arctic, near Svalbard and Greenland. Norwegians were not involved,” he said.

Whales were caught commercially. But if you look at the numbers, whales were not threatened with extinction in the same way as they were in the 20th century, Basberg says.

Norway and Great Britain dominated in the first decades

Most viewed

Large whales such as sperm whales and bowhead whales, were also caught in earlier decades.

Norwegian technology enabled whalers to start hunting the largest whales from the second half of the 19th century. The invention of fat curing created new markets for whale oil.

The expansion to Antarctica was led by Norwegians. In the early 20th century, British companies joined.

“I would say that the major expansion in the industry in the first 20-30 years of the 20th century was a Norwegian-British affair,” Basberg said.

“Later, more nations got involved. Germany was relatively large. After the war, Japan and the Soviet Union began whaling. Norway's relative share fell steadily,” he said.

Norway's share of the Antarctic catch was 70 per cent in 1928. Norwegians comprised nearly 100 per cent of the crews on foreign fishing fleets.

In 1938, Norway's share of the catch was 30 per cent and comprised 60 per cent of the crews on foreign whaling fleets, according to the Store Norske Leksikon.

In 1938, almost all the catch took place in the Antarctic, and only two percent of whale oil production came from other ocean areas.

Products were needed

A lot of whales were also caught after the Second World War. At that time there was a great shortage of fat globally.

The peak of the catch came around 1960, when 75,000 large whales were killed annually, Ytreberg writes in his book.

The fat and margarine industries needed the products that came from whaling, Basberg said

“It was an industry that had a brutal and bloody side, but it created products that nations wanted,” he said.

Whaling meant a lot in Norway’s Vestfold region.

“It was an alternative to becoming a sailor. It was secure work for many years and provided work for many residents. Compared to being a sailor, it was considered an attractive profession, because you were only gone for half a year and not three years, as sailors often were,” he said.

What saved whales?

What was it that saved whales? Was it research and political effort that won out, or was it something else?

“That’s a complicated question,” Ytreberg said.

He refers to research done by D. Graham Burnett presented in the book ‘The Sounding of the Whale’.

“His conclusion is that the whaling moratorium did not result from international cooperation or research winning over whaling interests,” Ytreberg said.

“As long as there was a lot of money in whaling, so that it played an important role for employment and profit, these considerations were allowed to dominate over considerations for the conservation of the species,” Ytreberg said.

“It was only when the whale began to disappear, so that the profit and workplace interests faded away, that consideration for the whale and conservation of stocks could win out,” he said.

Public opinion against whaling came after this, says Ytreberg.

The problems could not be controlled

Can we learn something from history? Ytreberg describes the whaling era as the first oil age.

“I have tried to write the book so that it should be possible to draw parallels to the second oil age, which we are in now,” Ytreberg said.

He refers to today's problems with species extinction and pollution from oil and plastic.

“Today we are up to the challenge of maximizing the benefits and controlling the problems with mineral oil. What the history of industrial whaling offers us is a historical example of how problems that got out of control took over,” he said.

Those who died and lived on

Ytreberg is also interested the experience of the workers who returned home and continued their lives in Norway after the industrial capture was over.

“They lived on a bit like soldiers who had returned home from a lost war. People aren't necessarily that interested in hearing about your experiences. I think the whalers had to endure a good deal of hindsight from the generations that followed,” he said.

“It has been important for me to think the opposite, to actively try to avoid feeling condescending to the workers, but rather to try to get closer to their experiences as witnesses and ordinary participants in the extermination,” he said.

What made the strongest impression on Ytreberg, however, were the stories of whalers who put their lives on the line.

“The accounts of both fatal accidents and suicides made an impression on me. Thinking about a life where death is so present has permeated the book in many ways,” he said.

On Deception Island, the horseshoe-shaped island with floating cookhouses in the lagoon, two burial sites remained after the whaling had stopped. One was for the whalers, with a cross over the dead. And one on the beach, where whale skeletons lie, bleached white by the sun.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no