They have been described as solitary, unsocial, and rather boring

"I’m convinced that their lives are much more exciting than that," says one whale researcher

And when researchers used satellite tags, they found a surprising similarity between sperm whales and humans

All sperm whales off the Norwegian coasts are males. Their lives are far more interesting than we imagined

Males used to be regarded as loners.

Earlier sources describe male sperm whales as becoming more unsocial the older they get, according to whale researcher Tiu Similä.

“They’ve always been described as solitary, and that they’re up here in the north just to feed,” she says.

New observations offer a more nuanced picture of the male whales.

“I’m convinced that their lives are much more exciting,” she says.

Leave the girls behind

Male and female whales live somewhat different lives.

Female sperm whales live in pods of 10 to 12 animals in warm waters.

They have close ties to each other and may stay together for life. They also join other pods for periods of time.

The females have different dialects that distinguish them from other clans that may consist of thousands of individuals.

The lives of the males can seem somewhat boring in comparison.

“When the boys reach puberty, they leave these groups,” says Similä.

Boys’ clubs

“The males’ whole behaviour changes, and life changes dramatically,” the whale researcher says.

The juvenile males gather in boys' clubs for a short period. In the North Atlantic, these young males eventually head north.

These are by no means retired, impotent males; they’re virile and get aroused all year round – a bit like us.

They often end up spread along the edge of the continental shelf of Northern Norway and all the way up to northern parts of Svalbard.

The edge of the continental shelf is where it ends and slopes down into the deep ocean.

Male sperm whales never become part of a pod again. They feed and fatten up in the north. They apparently live alone. Much less research has been done on the males in the north than the females further south, says Similä.

“Male sperm whales have in many ways been neglected and regarded as uninteresting,” she says.

World's largest brain

Researchers are now in the process of uncovering more information about the lives of the males in the north.

They are special and really exciting animals, according to whale researcher and photographer Audun Rikardsen.

“The sperm whale has the largest brain of any animal that has lived on Earth, even bigger than the blue whale,” he says.

“They live in a world of sound, and have different kinds of clicking sounds. Their clicking sound is the most powerful sound an animal can produce.”

They use the sounds for echolocation and communication.

Sperm whales are also one of the species that dive the deepest, sometimes to depths greater than 2,000 metres, and they can hold their breath for up to two hours.

At Andenes, the edge of the continental shelf is close to land. You don't need to travel far to see sperm whales, making the area ideal for whale watching.

Swimming together

Researchers have already noticed interesting traits in the behaviour of the males.

They are not as solitary as we might think.

“In winter and early spring, we see male sperm whales together, often very synchronised in their movements. There’s a lot of communicating going on,” says Similä.

Audun Rikardsen says the same.

“Sometimes they swim perfectly parallel, side by side, and they often move into shallower waters. It seems that especially in late winter and spring, they exhibit social behaviour,” he says.

Doctoral fellow Zoë Morange has also observed that seasonal changes play a role in which individuals are seen in the summer and in the winter. Researchers don’t yet know the reasons for this.

The project (see fact box) officially started in 2020 and a lot of different information is being collected. Similä points to the advantages of being employed as a researcher at a whale-watching company.

“We’re out every day, weather permitting. It's brilliant,” she says.

Calling to each other

In addition to clicking sounds, the researchers have heard the males produce so-called 'clangs'.

This powerful sound spreads in all directions, unlike the usual clicking sounds that are sent straight ahead like a sonar. These clangs are most often heard when several males are together. It is probably a form of social communication, says Rikardsen.

Are they saying 'hello'? Or does the clang sound have multiple meanings? The researchers are not sure what the sound is communicating.

“The sounds probably contain much more information than we think. They might sound similar to our human ears. But there are a lot of frequencies, and a whale probably receives much more information from one ‘clang’ than what we humans are able to pick up,” says Rikardsen.

One resemblance to humans

The researchers have satellite-tagged several males. They found a surprising similarity between sperm whales and humans.

I think he might have said something like ‘I'm from the Caribbean’. Then the older male came and took care of him.

Sperm whales do not appear to have a mating season. This contrasts with the vast majority of other animals on the planet, which usually have a fixed time of year when they mate, says Rikardsen. Humans don't have a mating season either.

The researchers have managed to follow the migrations of sperm whales over many months via the satellite tags. They showed that the whales migrated all the way south in search of females. But this did not happen at any set time.

Some people previously believed that since males can be seen up north all year round, many of them must be retired males who have stopped mating, according to Rikardsen.

“We now know that they migrate south throughout the year and thus don’t have a defined mating season. These are by no means retired, impotent males; they’re virile and get aroused all year round – a bit like us,” he says.

Their migration probably has to do with the whales feeling healthy and robust, which probably stimulates their desire to mate.

From Newfoundland to Cape Verde

The sperm whales in the north also do not have a particular area they go to mate, as was previously thought.

It was assumed that most whales went to the Azores off Portugal, says Rikardsen. This is because a few males that have been seen at Vesterålen were also observed in the Azores, where you can easily go out to see them.

“We’ve followed 10 to 12 animals that have migrated southward and northward again. They seem to spread throughout the Atlantic rather than having a defined mating area," Rikardsen says.

The whales travel to the deep seas off Newfoundland, Bermuda, Brazil, Cape Verde off Africa, or south of the Azores.

Two of the tagged males also travelled together part of the way. One started out two days earlier and slowed down in deep waters west of Trondheim, where the other one caught up to it. Then they travelled together, before they again parted ways south of England.

Most viewed

“They come together, talk a bit, maybe exchange some experiences, and then part again. They’re probably more social than we thought,” he says.

"I'm from the Caribbean"

Rikardsen believes that the fact that mating is spread over time and space indicates that there is little competition among the males.

It was previously assumed that they meet in one place and have boxing matches and fight. This assumption is based on the fact that some whales have scars that indicate injuries.

But no one has observed such fights, and Rikardsen doubts that they are the norm.

Tiu Similä says she has not observed aggression among the males off Vesterålen. Quite the contrary.

In 2020, she saw a young male sperm whale that had presumably left its pod in the south and headed north for the first time.

Then Similä heard it using clicking sounds reminiscent of Morse code, called codas. These sounds indicate pod affiliation and are rarely used by males in the north.

“It was a very young male sperm whale, and he tried using codas, when he suddenly found a much larger male beside him. I’m just speculating, but I think he might have said something like ‘I'm from the Caribbean’. Then the older male came and took care of him,” she says.

Do older males have some sort of guidance function for young males who travel to the north for the first time? This is one of the questions Similä wants to learn more about.

Steal fish

Along with satellite tagging, researchers have also used camera tags that are attached to the whales' heads with a suction cup.

These tags film what the whale does, while also recording sound. They stay on for up to 24 hours, and also record depth, temperature, acceleration, as well as the whale's body angle and compass heading with a resolution of up to several hundred measurements per second, says Rikardsen.

The tags also have lights that turn on when it gets dark, and the researchers are interesting in seeing what the whales eat down in the depths.

Sperm whales have started to steal Greenland halibut from the lines and nets of fishermen along the edge of the continental shelf.

“We don't know how they do this, and we’re hoping to get answers from these tags so that we can implement measures that might be able to limit the thievery,” says Rikardsen.

“The theft has increased and there are constantly new whales that join during the very short Greenland halibut fishing season,” says Similä.

Snot and blubber

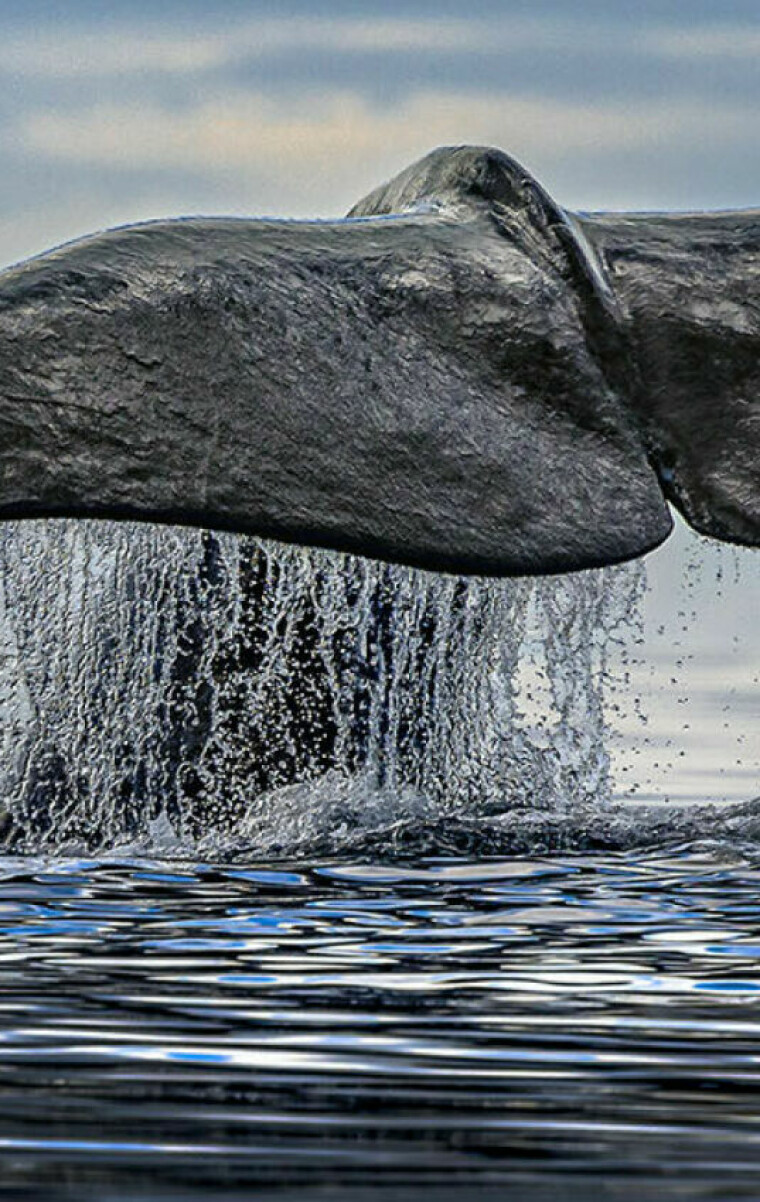

Whale-watching companies take pictures of the tail fin of the whales that are observed. Tourists can also do this and contribute to the research.

“Every whale has its own unique tail pattern, almost like a fingerprint. This means that we can identify them over time and in different areas where pictures are taken,” says Rikardsen.

“When we’re at Andenes, we also use Whale2Sea's boats and conduct several other types of sampling, including taking samples of skin and blubber.”

These samples are taken by shooting a very small dart into the animals' skin. This provides information about genetics, kinship, diet, and environmental toxins. The researchers are working on a publication about environmental toxins in sperm whales.

“We can already confirm that the whales have surprisingly and worryingly high levels of environmental toxins,” he says.

Two students are collecting water samples that are analysed for environmental DNA. The samples reveal how many whales are in an area from just one litre of water.

A doctoral student takes blow samples, that is, samples of water and snot that the whales blow out from the blowhole on their head, which is actually their nose. This can tell us which bacteria and viruses the whale has and thus reveal information about the whales’ health condition.

Hydrophones out in the water record sound and chatter from the whales.

The researchers also collect the whale's faeces to study what it has eaten. You might think that this would be easy to collect, given that it is such a large animal, but the whale's faeces are liquid and consist of very small particles.

The solution is that one of the team members has to jump into the water when they see a whale defecating and then catch some of the particles with a very fine mesh net.

Contributing to knowledge-based whale tourism

There is much to tackle and write about.

“The project will eventually generate a lot of scientific articles, including migrating and diving behaviour, diet, environmental toxins, health condition, and genetics. It’s a very comprehensive project involving many researchers and students,” says Similä.

The main purpose of the entire project is twofold, according to Rikardsen.

“We want the project to provide more knowledge about sperm whales and also contribute to more sustainable and knowledge-based whale tourism.

“The sperm whale is the most important species for year-round whale tourism in Vesterålen. All the information and visual material that comes out of the project will be able to be used freely by the whale tourism companies and will help make this industry more knowledge-based for both tourists and operators," he says.

———

(Photo: Audun Rikardsen also took the photos at the top of the article.)

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no