Dementia researcher:

“A medical scandal”

This summer, it was revealed that a drug capable of slowing the early progression of Alzheimer's disease would not be approved in Europe. Here are some reactions to this decision.

There was significant hope surrounding this medication, which has been described as a breakthrough in Alzheimer's treatment.

The medication had already been approved for use in the USA last year. If it had been approved in Europe, it would likely have been made available in Norway as well.

However, this summer, the European rejection was confirmed.

“A medical scandal”

Scandinavian researchers have expressed both surprise and concern.

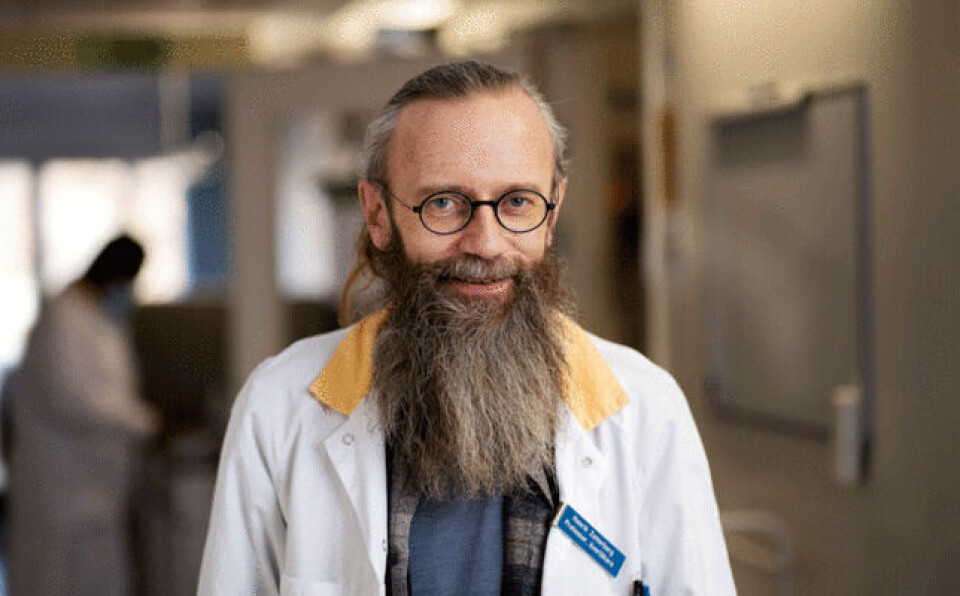

Henrik Zetterberg, a dementia researcher at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, has been one of the most vocal critics.

“I believe we are witnessing a medical scandal unfolding here,” he tells Life Science Sweden (link in Swedish).

He is highly critical of the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) decision, which was made at the end of July.

Too strict on conflicts of interest

Zetterberg argues that the EMA has overly strict rules regarding conflicts of interest in their expert groups, which leads to the exclusion of the most knowledgeable experts from the decision-making process for approving medications.

He was invited to join the expert group but was excluded because his research group collaborates with pharmaceutical companies to measure biomarkers.

Zetterberg points out that this work is done for all pharmaceutical companies, not just those behind lecanemab.

“As professors in Sweden and Europe, we have a duty to help society, patients, and pharmaceutical companies improve the situation,” he tells Life Science Sweden.

Approved in the UK

Last week, it was announced that the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency had approved the Alzheimer's medication for patients in the early stages of the disease, according to gov.uk.

The EMA justified its rejection by stating that the medication’s benefits do not outweigh the risk of serious side effects, according to their official statement.

Henrik Zetterberg now believes it could take several years before the medication becomes available to European patients.

Impact on similar medications

Danish dementia researcher Kristian Steen Frederiksen, from the National Knowledge Center for Dementia at Rigshospitalet in Denmark, believes that a European rejection of the medication could hinder the development of similar Alzheimer's treatments.

A similar treatment involving another drug, donanemab, is underway. Frederiksen doubts that this will gain EMA approval either.

“I believe EMA will reach the same decision because the current results for the two antibodies are similar,” he tells Danish news agency Ritzau.

Surprised by the decision

In Norway, Geir Selbæk, head of research and professor at the Norwegian National Centre for Ageing and Health and professor of geriatrics at the University of Oslo, expressed surprise at the decisions made in both Europe and the UK.

“At first, I was a bit surprised that EMA did not approve lecanemab in Europe. Now I am surprised that the UK has approved the medication,” he says.

This highlights the difficult balance between benefit and risk, he said in an interview with Ageing and Health (link in Norwegian).

Little is known about long-term effects

The UK National Health Service (NHS) will not offer the medication in the public healthcare system for the time being.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argues that the high cost of the drug and the need for intensive monitoring of side effects mean that it cannot be considered good value for taxpayer money.

NICE also notes that there is insufficient documentation on the long-term effects of the treatment.

Significant breakthroughs

Alzheimer's is characterised by abnormal accumulations of a protein in the brain called beta-amyloid. The new drugs, lecanemab and donanemab, target this protein.

Beta-amyloid forms plaques in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. The medication aims to attack these plaques, thereby slowing the disease’s progression.

These are significant scientific breakthroughs, Geir Selbæk said in an interview with forskning.no in February this year (link in Norwegian).

Uncertain impact

However, Selbæk believes that the impact on patients remains uncertain.

In a recent large study covered by forskning.no, researchers found modest differences between patients who used the medication and those with Alzheimer's who did not.

Most viewed

The researchers found that those who took the drug had less beta-amyloid in their brains. However, the effect on the patients' memory and function was modest.

“This study shows that the clinical effect is lower than what is often required for approval of a treatment,” Selbæk said in the interview.

Well-documented side effects

The side effects of the medication are well documented.

In some cases, patients experience mild brain oedema and small haemorrhages. In rare cases, the treatment can lead to life-threatening brain haemorrhages.

In 2022, it became clear that two deaths could be linked to the medication.

In addition to the side effects, the medication is expensive. Diagnosing Alzheimer's is also costly and challenging. It is possible that the medicine’s effectiveness is better if treatment starts earlier.

This would require diagnosing Alzheimer's disease several years before people show clear symptoms. Doctors would first need to detect the presence of amyloid in the brain. Then, after starting the drug, patients would need regular MRI scans of their brains.

Currently, we do not have good routines for this, Selbæk told forskning.no in 2022.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no