What do pigs and birds have in common?

They have a shared instinctual trait that defies expectations.

There are 90,000 sows living in Norway. They could fill the Wembley Stadium.

They live indoors in pigsties all year round.

However, had they lived outdoors in the forest and fields, an ancient instinct would have driven them to build nests.

The instinct kicks in a few days before a sow is ready to give birth. She separates from the rest of the group to start her search for the perfect nesting spot.

Prefer a place with a view

“They may wander a significant distance in search of a suitable thicket. Ideally, it should offer a view to oversee the surroundings,” says Ellen Marie Rosvold. She is a researcher at Nord University.

When the sow finds a nice place, perhaps sheltered by a rock or tree, she digs a pit.

“With their legs and snouts, they excavate and forage, gathering nesting materials,” Rosvold says.

They gather twigs, branches, moss, and grass, incorporating everything into the pit.

“They spend a lot of time arranging and decorating, so that it becomes nice. And when the birth approaches, they dig themselves down into the mound,” she says.

The newborn piglets are small and wet when they come out, and they lose heat quickly. The nest protects both the mother and her offspring against the cold and predators.

Wanted to build themselves

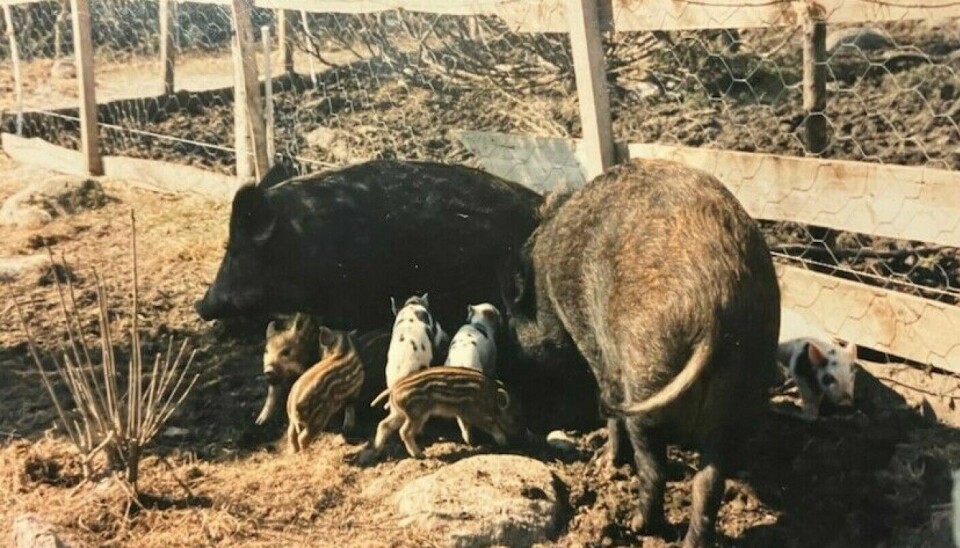

Åsmund Kalstveit from Western Norway had wild boars a few years ago. They are the same species as domestic pigs.

He witnessed his two sows build their nests up close.

As their births approached, he prepared a warm space for them.

Both were to have young, and when the birth approached, he made a warm place for them.

“I built a house on an old trailer and filled it with straw,” he says.

However, the following morning revealed the sows shuttling between the trailer and a nearby birch grove. Their mouths were brimming with straw from the trailer.

“There, they built a nest in the snow under a large rock. They would rather be in the nest out in the cold than inside the draft-free trailer,” he says.

One day it rained heavily. Kalstveit put a tarp over the nest.

“But they pulled the tarp off the nest and dragged it far away. They even positioned a juniper bush vertically in the nest. We laughed a bit because it looked like they were decorating for Christmas,” he says.

Entitled to nesting materials

If given the chance, pigs use grass and branches for their nests when outdoors. But what do they do when living inside a pigsty?

“Building nests is part of the pigs’ instincts and biology. Towards the end of pregnancy, hormonal changes induce restlessness and initiate the search for suitable nesting sites,” says Rosvold.

They are entitled to that, according to the law on pig farming. The law grants sows the right to appropriate nesting materials starting three days before giving birth.

However, this has not always been the case.

In the 1950s, new methods of animal husbandry were introduced, according to Kristian Bjørkdahl and Karen Lykke. The two researchers have written a book about meat production in Norway.

The number of pigs per farm increased. Work tasks became automated. Animal welfare was sidelined for profit.

Confined in a metal frame

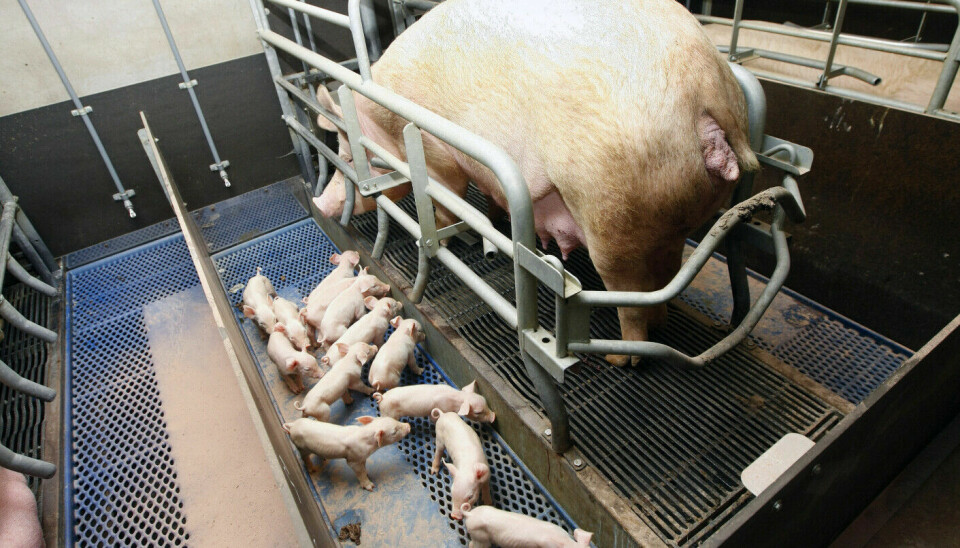

Everything was designed to be efficient. So, when the sow was about to give birth, she was confined in a narrow metal frame. This method is known as fixation.

The aim was to prevent the mother from lying on the piglets after birth and crushing them to death.

The result was that she could not move or find a comfortable lying position. She was also unable communicate with or sniff the pigs in the neighbouring pen or her own piglets.

And she certainly could not build a nest.

Fixation was banned in Norway 25 years ago, although the law allows for exceptions.

“Only Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland have legislated nest-building. All other European countries still practice fixation of sows,” says Rosvold.

Straw calms them down

Norwegian sows are now free to roam in their pens and are allowed to build nests, but with what?

The law does not specify what constitutes suitable materials.

This is what Ellen Marie Rosvold has researched. Three groups of female pigs were each given different materials. Which was best among sawdust, peat, and straw?

Those given straw spend more time building their nest. It’s easier for them to carry the straw around in their mouths. They are calmer and rest more before giving birth, according to Rosvold.

“Moreover, the births are shorter for the sows that receive straw compared to those given and peat,” she says.

Additionally, the sows become better mothers when they are allowed to build nests out of straw, the researcher says.

All pigs like straw

“Other sows might nip, push, and vocalise aggressively towards their piglets. But the sows with straw nests tend to be kinder. Perhaps, it's easier for them to embrace motherhood when they can fulfill their instincts before and throughout birthing. Stress likely plays a significant role,” says Rosvold.

According to the law, piglets must stay with their mother for at least 28 days. 12 per cent of them die during this time, although the mortality rate has decreased over the last ten years, the pig researcher notes.

“Some are crushed to death. Others die of starvation because there’s fierce competition for milk. Some also die because they get too cold,” she says.

Pigs like straw, even when they are not about to give birth. And they have a right to materials they can root around in.

Pigs raised for slaughter live closely together in Norwegian pigsties.

“This can make the animals stressed and lead to them biting each other. When they have something to do and can root around in straw, they become calmer,” says Rosvold.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

References:

Rosvold, E.M. & Andersen, I-L. Straw vs. peat as nest-building material – The impact on farrowing duration and piglet mortality in loose-housed sows, Livestock Science, vol. 229, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.livsci.2019.05.014

Great Norwegian Encyclopedia: Gris (Pigs), 2023.

Lovdata: Forskrivt om hold av svin (Regulation on the keeping of pigs), 2023.