Archaeologists' most exciting finds:

This image was carved 3,000 years ago. Then it was buried by a massive landslide

The small stone with images on both sides was found at a 3,000-year-old cult site. Was the site in use until the moment disaster struck?

Around 800 BCE, a landslide occurred in Gauldal, a river valley in Central Norway.

"The whole area is covered in clay from that landslide," says Hanne Bryn.

Bryn, then working as an archaeologist for the Sør-Trøndelag County Municipality, was sent to the site in 2014. She quickly uncovered signs of human activity from long ago.

The E6 highway was to be expanded, requiring an archaeological survey. Bryn returned to the site, now as an archaeologist with the NTNU University Museum, where she still works today.

They had to search a vast area covered in clay layers up to three metres thick.

It took longer than expected. Specifically, two summers instead of one.

But what they found beneath the clay was worth it.

"It's a very special find. We’ve never found anything quite like it. In a Central Norwegian context, it’s entirely unique," says Bryn.

Burial structures and carved stones

What the archaeologists uncovered in Gauldal was a 3,000-year-old cult site – a place where people in the past practised their religion.

The site consisted of two main areas, Bryn explains.

Each section featured a building with associated burial structures.

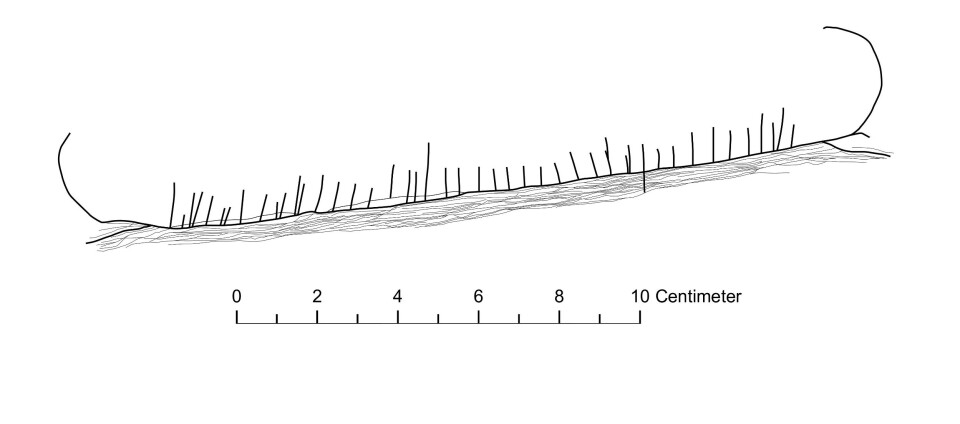

The buildings were longhouses measuring about 10 to 12 metres. Not particularly large.

Near one of the longhouses lay a somewhat larger burial cairn, a burial mound made of stone. There were also three stone slab chambers here, a kind of burial chamber built from flat stone slabs.

Scattered around the house and the burial site were loose stones decorated with carvings.

One stone found in the burial cairn had a clearly pecked footprint, complete with toes. It also featured a cup mark – a round depression, about 5 to 10 centimetres wide, carved into the surface.

Beside the house, a semicircle of stones was arranged. One had the outline of a footprint and a cup mark, while another had several cup marks.

At one end of the longhouse was a collection of slightly larger stones.

Hidden beneath them, Bryn found a small stone with engravings on both sides.

Discovered at the site where it was once used

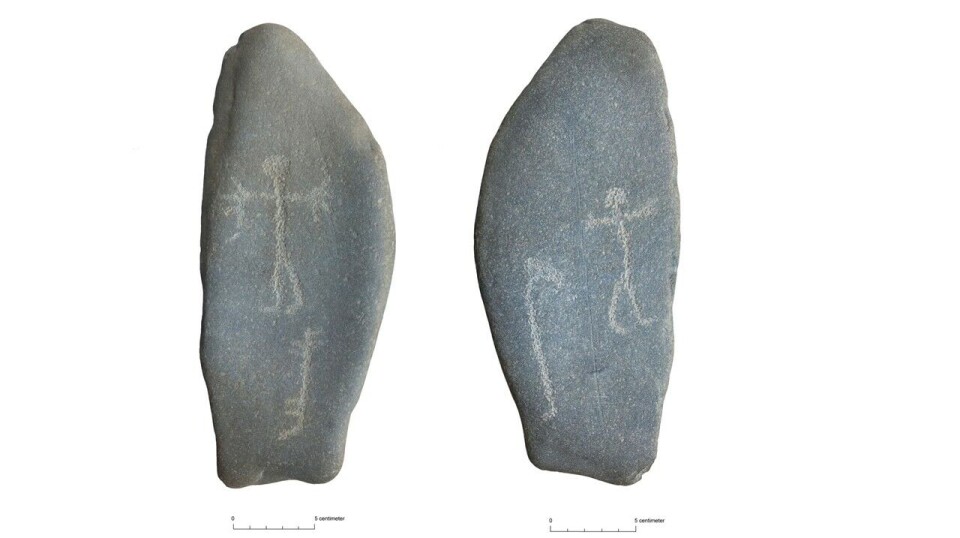

The stone measures about 20 by 10 centimetres. Like a small photograph.

On one side, a human figure and what appears to be a dog are pecked into the surface.

Above the hand of the human figure, a bow and arrow are engraved, created using a different technique than the rest of the image.

On the other side of the small stone are another human figure and an unidentified shape. These, too, are made with a pecking technique.

Alongside the human figure, a ship is engraved.

"It's a very special find," says Bryn. "It's so small. It's portable, you could carry it in your pocket."

Most rock art in Norway is carved or pecked directly into bedrock.

"Finding portable stones like this, lying in the landscape where they were once used, is especially rare. There aren't many discoveries that compare," says Bryn.

A site of ritual importance

The archaeologists did not find traces of settlements beneath the clay.

They did uncover some cooking pits and a fire pit likely used for bronze casting. But the area between the two zones with longhouses and graves was otherwise empty. It likely wasn't a place where people lived.

Most viewed

They came here for something else.

"It points to a site of special significance," says Bryn.

What the carved stone was actually used for is impossible for archaeologists to say with certainty.

"But these stones had a ritual significance, together with the burial structures," says Bryn.

Were people there when the landslide hit?

In the stone slab chambers, archaeologists found burnt bones.

"It's been confirmed that these were human bones, and they've been dated roughly to between 1000 and 800 BCE," says Bryn.

That’s also the estimated time of the landslide.

Could the site have still been active when the clay came rushing down and sealed everything beneath it?

"There are no traces of people here. It wasn't a Pompeii, though we did wonder about that ourselves," she says, referring to the Roman city that was buried and preserved after a massive volcanic eruption from Mount Vesuvius in the year 79.

Whether the cult site was still actively used when the landslide occurred is difficult to determine, according to Bryn.

They might find more this summer

Near Gaulfossen, archaeologists have found numerous rock carvings, Bryn says. Carvings have also been found on a plateau south of the landslide pit.

"This whole area is a Bronze Age cultural landscape. There was quite a bit of activity here," she says.

Bryn and her team hope to uncover more this summer as fieldwork continues.

Still working under the backdrop of the E6 highway expansion, they are now excavating a plateau slightly higher up, just behind the pit where the clay slide originated.

"So far, nothing exceptional has turned up, but we do have signs that people dug into the ground here, so we're calling it a settlement area," says Bryn.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.