Archaeologists’ most exciting finds:

“I caught a glimmer of gold and glass”

A glass goblet from the Roman Empire was unearthed in Eastern Norway.

Jørgen Bøckman recalls it like a scene in slow motion. The young archaeologist frantically waved his arms at the man on the excavator, shouting for him to stop, before sprinting towards the bucket.

As he ran, his mind raced. What could this be? And more importantly, from when?

Barely visible beneath the bucket, something peeked out from the soil. The sunlight made it sparkle with hints of gold and glass.

The gilded metal band left no doubt in Bøckman’s mind.

“When I saw the pattern on the metal band and design of the glass shards, I instantly knew what the full goblet looked like, when it’s from, and what kind of decoration it had,” he tells sciencenorway.no.

What Bøckman found was a glass from the Migration Period in Norway. Originally made in the Roman Empire, it had somehow been transported to Norway and later decorated by Scandinavian Iron Age people, possibly right there in Brumunddal where it was discovered.

One of his first assignments

This was one of Bøckman’s very first archaeological digs.

As a student of archaeology, he joined an expedition to Brumunddal, Eastern Norway, in 2002, where prehistoric settlement remains had been uncovered.

The site, known as Lille Børke, was being excavated for evidence of postholes from large longhouses and cooking pits.

“It was an incredibly exciting place for an archaeology student to be,” says Bøckman.

The archaeologists were conducting mechanical surface stripping – removing topsoil with an excavator to see what lay beneath.

This was when the newly-graduated archaeologist made what would be his most exciting discovery to date.

Recognised the pattern

According to Bøckman, the find was exceptional.

The glass, tall like a goblet, was slightly green-tinted with waves running up and down its body and a spiral pattern at the top.

It was also decorated with several metal bands.

These bands, made of silver and gilded, were intricately designed. The uppermost band featured a winding pattern, typical of the local style of that time.

“It’s a style known as Salin's Style I, which is very easy to recognise,” he says.

That is how Bøckman instantly knew what he had uncovered in the pit at Lille Børke.

The band’s purpose

Bøckman explains that the gilded band was placed on the glass specifically to conceal damage.

“It was standard practice to repair glasses this way,” he says.

The discovery of the glass in Eastern Norway is unique. Roman glass goblets are usually found along Norway’s southern and western coasts.

“But this time, we found one in Brumunddal, an area with few previous finds,” he says.

Even though Bøckman recognised the goblet before he reached the excavation site, its significance only became apparent much later.

“It completely reshaped the map of where such objects have been found in Norway,” he says.

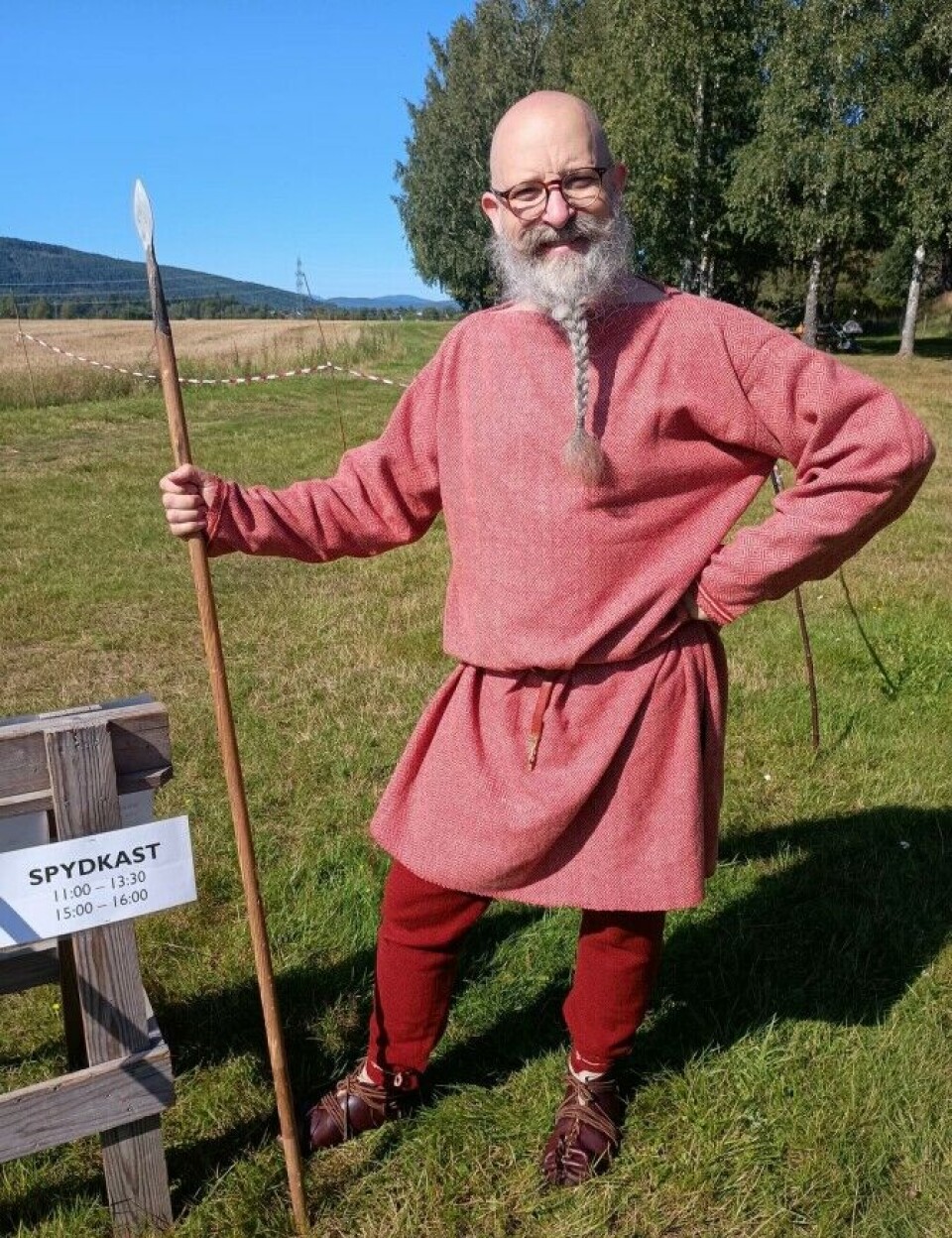

Today, Bøckman works as an educator at Veien Cultural Heritage Park.

The Migration Period

At that time, no one in Northern Europe could make glass, Bøckman explains. Archaeologists are therefore confident that the goblet did not originate here.

“The closest place it could have come from is somewhere in central Europe, likely in the northern region of the Roman Empire,” says Bøckman.

Carbon dating of the find from Lille Børke revealed that the settlement and the glass date back to the Migration Period. This period is generally considered to be between 400 and 570 AD, depending on who you ask, Bøckman notes.

“This was a very significant period in European history. It was after the fall of the Roman Empire, but Scandinavia was still heavily influenced by Roman culture,” he says.

People travelled abroad and returned with goods from the Roman Empire, which they adapted in their own way, he explains.

“In much of the material from the Migration Period, we can see the early stages of what would later become the Viking Age,” says Bøckman.

Who owned the glass?

We will never know exactly who used and owned the glass.

“When you find a single object, you can’t say much about who held it or owned it. But we assume it belonged to someone high up in society,” says Bøckman.

If not the local chieftain or petty king, it was certainly someone in a prominent position in the community.

Lille Børke is located on a small hill with a great view over Brumunddalen.

“It’s clearly a prestigious place,” says Bøckman.

Why was it buried?

Bøckman and his colleagues believe the goblet was intentionally buried in the pit.

“It was almost certainly placed in the ground by someone. It turns out that there was a house at the same location, which raises the question: Why was it buried here? It doesn’t appear to be a grave,” says Bøckman.

“Most personal belongings from the Iron Age are found in graves, preserved for posterity. Otherwise, they usually disappear,” he adds.

When archaeologists find items like this in unusual locations, they have to interpret the context, according to Bøckman.

He suggests it may have been a treasure someone buried to keep safe.

“It could also have been some kind of votive offering or a sacrifice to the house,” he suggests. “And, of course, it’s possible there’s a grave inside the house that we haven’t yet found, though this would be highly unusual. There’s no tradition of burying people inside houses.”

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Lislerud, A. Arkeologiske undersøkelser på Lille Børke, Børke Nordre, gårdsnummer 30, bruksnummer 3, Ringsaker kommune, Hedmark Fylke (Archaeological investigations at Lille Børke, Børke Nordre, farm number 30, plot number 3, Ringsaker municipality, Hedmark County), The university’s cultural history museums, 2003.