Why do we have consciousness? Researchers are deeply divided

But perhaps everyone is somewhat right? A Norwegian professor is attempting to reconcile the seemingly conflicting theories.

You might think that something as philosophical as consciousness research would be conducted in subdued form.

This is not the case.

At the end of 2023, a public dispute broke out between different academic communities in the field.

More than a hundred researchers had signed a petition accusing one of the most popular consciousness theories of being pseudoscience – that is, research that pretends to be scientific but really isn't.

Other researchers completely disagreed. They argued that the accusations were unfounded and that the rival theories of consciousness were no more scientific.

Underlying it all is an existential dilemma:

If the popular theory is correct, consciousness could exist in many more creatures than we had thought. Maybe even in inanimate things.

If the theory is correct, the consequences could be significant in areas like artificial intelligence, lab-grown organs, and animal testing. It could even impact views on abortion.

Ancient mystery

The question is as old as it is fundamental:

What exactly is consciousness?

What enables us as individuals to experience being present in the world – taking in our surroundings through sight, hearing, smell, and taste – and to have an idea of ourselves and an inner life of thoughts and feelings?

How on earth can these subjective experiences arise in a lump of biological material? What mechanisms are behind this? And what is the minimum requirement for these mechanisms to start working?

Does consciousness only exist in immensely complicated systems, like the brains of humans and primates? Or can there be small sparks of consciousness even in insects? Or trees? Or computers?

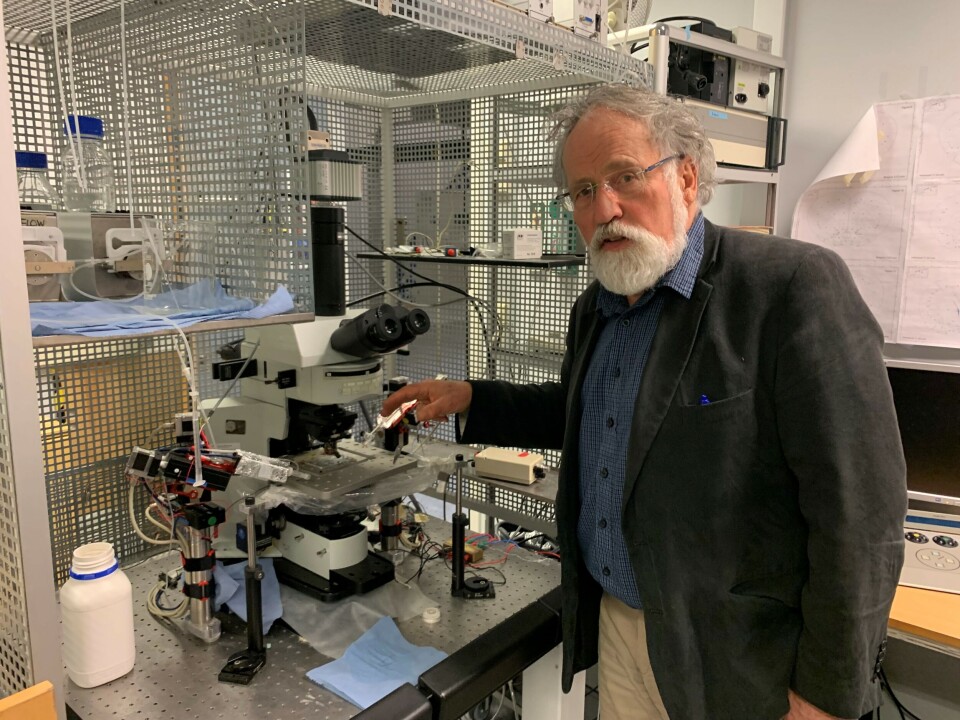

“Philosophers have been grappling with these questions for millennia,” says Johan Storm, a professor of neurophysiology at the University of Oslo.

But in recent decades, something has changed:

Brain researchers have become much more actively engaged. Storm is one of them.

Many theories – but which are correct?

“For a long time, consciousness was almost a non-topic for the majority of brain researchers and psychologists,” says Storm.

“This was largely due to behaviourism – a trend that dominated psychology in the 20th century – which claimed that it was unscientific to study subjective experiences."

But since the turn of the millennium, attitudes have changed, and we’re seeing progress in the field, Storm explains.

He believes part of the reason for this is the great technological advancements for measuring brain activity. We now know much more, both about the patterns of activity in the entire brain and what goes on in each individual brain cell.

These developments have given researchers many ideas about what could give rise to the phenomenon of consciousness.

There are actually up to 20 serious theories about consciousness, according to an article in Quanta Magazine in 2023.

Around five of them can be considered the leading theories. And one of these is the much-discussed theory that was recently accused of being pseudoscience.

Calculating the degree of consciousness

The controversial theory is called integrated information theory (IIT).

“IIT is a very ambitious theory,” says Storm.

Very simply put, IIT says that consciousness arises when there is both a high information content in the brain and at the same time a very high degree of interaction – or integration – between the information in the different elements of the brain.

“This kind of interaction means that the sum of integrated information is very large, and that the system as a whole is much larger than the sum of information in the individual parts,” he says.

The theory even states that it is possible to calculate a value that indicates the degree of consciousness, although this is impossible for our brain to do in practice, according to Storm.

Explaining the cerebellum paradox

“A theory like this could explain a number of strange things, like why the cerebellum isn’t important for consciousness. If you remove the cerebellum, you end up with problems like poor balance, but it has no impact on consciousness,” says Storm.

And that is despite the fact that the cerebellum is extremely complex and contains an awful lot of information.

“But the information in the cerebellum is much less integrated than information in the cerebral cortex. IIT highlights that the cerebellum consists of slightly more separate modules that don’t communicate as much with each other as the parts of the cerebral cortex do,” says Storm.

IIT has received quite a lot of attention. But it is by no means the only comprehensive theory of how consciousness arises.

Explosion of activity

Another main theory is called the global neuronal workspace theory (GNWT).

“The core idea here is that what becomes conscious is information that is important enough to be broadcast to many parts of the brain,” says Storm, elaborating:

Even though the brain is constantly being bombarded with enormous amounts of impressions, most of it never reaches consciousness. They’re not important enough to be spread to the whole brain.

But some information is significant enough to cross a threshold that ignites a kind of explosion of activity in the brain – causing the information to be broadcast throughout the system, so that we have a conscious experience.

Every cell is a whole computer

A third model – dendritic integration theory – takes us right down to the cellular level, says Storm.

Research in recent years has shown that brain cells are not at all like simple transistors that are either on or off. Quite the contrary.

"Every single neuron is like a computer. It has thousands of molecular mechanisms that process information in intricate ways within the cell. At the same time, each cell can have more than 20,000 connections to other neurons,” says Storm.

The cell has an extremely complicated system of connections and feedback loops, where new information that comes in through the system is matched with information the brain already has.

In certain situations, when new and old information match, an almost explosive reaction occurs where the cell sends a flurry of nerve impulses to other cells, according to Storm.

Researchers believe that precisely this type of event gives rise to conscious experiences.

Storm says this theory of consciousness might explain how anaesthesia works. That is, how anaesthetics can make us lose consciousness.

Research has shown that such substances inhibit the brain cells' ability to communicate internally and compare information. Thus, it never gets to send the flurry of impulses that yield conscious experiences.

But are the theories true?

In contrast to earlier times, there is now no shortage of theories about how the brain can give rise to consciousness.

The problem is that we do not know which one is correct.

Each theory is supported by scientific studies. Theories predict, for example, how the pattern of brain activity will look when we have conscious experiences. Numerous experiments have been conducted to test if reality matches these predictions.

This is how researchers have gathered evidence for the different hypotheses.

But often the results are inconclusive and open to interpretation. Researchers tend to design their experiments – and interpret the resulting data – in a way that supports their own favourite theory, according to the article in Quanta Magazine.

So we are no closer to a theoretical consensus. After decades of research, scientists have still not been able to prove or disprove any of the main theories.

Adversarial collaboration

This predicament led to the outcry and accusations of pseudoscience.

The gap between the theories led researchers to start a rather ambitious and rare project five years ago: an adversarial collaboration.

Leading researchers from two rival theories – IIT and GNWT – joined forces to set up a series of very thorough studies to test the theories against each other. The researchers agreed beforehand on what they were going to test and how the findings were to be interpreted.

The results came in June 2023.

They were revealed at the now-famous presentation at the 26th meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, which took place in New York in June 2023, writes Professor Philip Goff from Durham University on The Conversation website.

Finally, the world would know whether IIT or GNWT best explained the phenomenon of consciousness.

However, the answer was not as clear-cut as many researchers had hoped.

Letter of protest

The study simply showed that both theories were somewhat right and somewhat wrong. The results could neither fully confirm nor refute either of them, but overall, IIT possibly fared the best.

Some felt that the project and the answer were proof that science works as it should: The researchers conducted a thorough experiment and then had to take the results into consideration, regardless of which theory they initially supported.

Some of the opponents of IIT were upset and sent out a letter of protest, which was posted on PsyArXiv.

They wrote that IIT had received far too much attention in the media and that it was not really a leading theory at all. They were critical of the results of the rival study being presented as partial support for IIT.

Pseudoscience

The experiments tested only some rather peripheral and uninteresting parts of the theory, they argued in the petition, and the results could therefore not be cited as support for the theory as a whole.

On the contrary, the authors questioned whether it is even possible to test the theory in its entirety. They came to a rather startling conclusion:

Until a way is found to test the entire theory, IIT can be defined as pseudoscience – a real insult in scientific circles.

Not surprisingly, protests from other researchers arose soon after.

This criticism does not apply only to IIT. The core principles of any theory of consciousness are difficult to test, Professor Tim Bayne of Monash University wrote in The Conversation.

But the authors of the petition still saw it as their duty to warn against IIT.

They wrote that if the theory actually is correct, or if the general public believes it is correct, the consequences could be significant.

Are organs in labs conscious?

IIT is one of the theories that suggests consciousness is not only found in humans and other creatures with highly advanced brains.

According to IIT, consciousness could arise in any system with a certain degree of interaction – integration – of information.

The theory thus allows for forms of consciousness to arise in various contexts, such as artificial intelligence, lab-grown organs, and foetuses in the very early stages of pregnancy.

This could have major implications for ethical rules concerning everything from machines to abortion.

Moreover, the theory opens the door to the possibility that consciousness could be a common phenomenon permeating the universe – an idea called panpsychism.

The authors of the petition wrote that this idea is untestable, unscientific, 'magicalist', and incompatible with science as we know it.

It does not have to be war

Instead of uniting researchers with different theories, the adversarial collaboration seems to have led to even deeper divisions among consciousness researchers.

But the research field does not have to resort to trench warfare, Storm believes.

He and his colleagues have just published a research article arguing a point similar to the results from the duel between IIT and GNWT:

Maybe everyone is a little bit right?

Talking past each other

“We propose a completely different approach to this controversy. If you look closely, these theories are much more compatible than they appear at first glance,” says Storm.

As part of the large EU Human Brain Project, Storm and 11 EU colleagues compared five of the leading theories of consciousness, including IIT. Instead of looking for controversies, they searched for commonalities suggesting the theories could be united or complement each other.

Storm believes that much of the conflict revolves around the researchers partly talking past each other and attributing different meanings to words and concepts.

They are trying to explain different forms of consciousness and focus on mechanisms at quite different levels, such as the cellular level and the system level.

“People see things differently because they’re trying to explain different aspects of consciousness,” says Storm, illustrating the point with a famous Indian parable.

Seeing only a limited part of the whole

In the parable, seven blind men examine an elephant – an animal none of them have heard of before. They each encounter different parts of the animal.

One feels the trunk and concludes that it must be a snake. Another examines the ear and thinks it is a fan. The man who finds the leg thinks it is a tree trunk.

The men, of course, completely disagree with each other's conclusions because they only relate to their own limited part of the whole.

Storm and his colleagues are now trying to convince the world that the situation might be similar in consciousness research. They have created a large review article showing how the theories might be intertwined.

This article was recently published in the scientific journal Neuron, which used the opportunity to create a whole special issue on consciousness, where other research groups were invited to comment and fill in the picture.

It now remains to be seen if the effort will lead to more agreement among the proponents of the different theories.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no