The Stanford Prison Experiment is one of history's most famous psychology studies.

But it has been shown that the results from both this and many other studies in psychology can not be reproduced.

Research in psychology has serious problems, say researchers.

Something is wrong with psychological research

Almost all the studies in psychology confirm what the researchers believe. Should that set off alarm bells?

It’s probably every researcher’s dream:

You have a hypothesis – a bold supposition about how certain things are connected – which you test in a scientific study.

And when you look at the findings, they live up to your expectations. You were right! The results confirm your initial hypothesis.

A scientific victory – or is it?

Stop needing to win!

In 2022, psychology professor Gerald Haeffel made an urgent call to his colleagues worldwide:

Research psychologists need to get tired of winning every time!

One new survey that Haeffel refers to showed that 96 percent of psychological studies concluded that the hypothesis was correct.

That’s not good.

When scientists are almost always right, it is not a sign that they are geniuses but rather a disturbing hint that something is wrong with the studies.

Worrying study

The survey Haeffel referred to is by no means the first sign of problems in psychological research.

Several researchers had begun to question the quality of many investigations in the early 2010s.

And in 2015, a firebrand of a study was published in the scientific journal Science.

Researcher Brian Nosek and a large group of colleagues had set up a huge test.

They selected 100 random psychology studies that had recently been published in three prestigious scientific journals. Then the researchers simply ran the studies again to see if they would achieve the same results.

They didn't.

Replication crisis

Ninety-seven percent of the original studies confirmed the researchers' hypotheses. When exactly the same studies were conducted again, only 37 percent of them supported the hypothesis.

And even in these studies, the results were often far weaker than in the original studies.

Several major psychological truths were called into question in the wake of this and other investigations.

A significant percentage of what I learned as an undergraduate in psychology in 2001 has since been shown not to hold water.

The problems in the field are often referred to as a replication crisis. The problems within social psychology, which tries to explain how humans affect each other mentally, have been pointed to in particular. But other areas, such as clinical psychology, also appear to be affected.

The well-known statistician and science critic John Ioannidis wrote in 2022 that most of the documentation we have on psychotherapy is highly distorted.

“Most types of psychotherapy probably do little or no good, even when published literature suggests that they are very effective,” he wrote in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences.

Unhealthy research practices

Henrik Berg is a theory of science professor at the University of Bergen, with an educational background in psychology and philosophy. He agrees that psychology research is facing challenges.

The matter is complicated. Psychological mechanisms can be extremely complex, and setting up good studies without oversimplifying the phenomena is challenging.

Berg believes that some of the research in the field has undoubtedly been of low quality.

“In the last ten years, a number of rather unhealthy research practices in the health and psychology fields have come to light,” he says.

Maybe everyone couldn’t turn evil after all

Joar Øveraas Halvorsen is a specialist in clinical psychology and an associate professor at NTNU. He also believes that many of the studies in psychology are of poor quality. This in turn leads to a lot of the knowledge in the field being less reliable.

“We can say very few things with any great degree of certainty in my field. A significant proportion of what I learned as an undergraduate in psychology in 2001 has since been shown not to hold water,” he says.

For example, it was understood for a long time that almost all people can turn evil when given the chance.

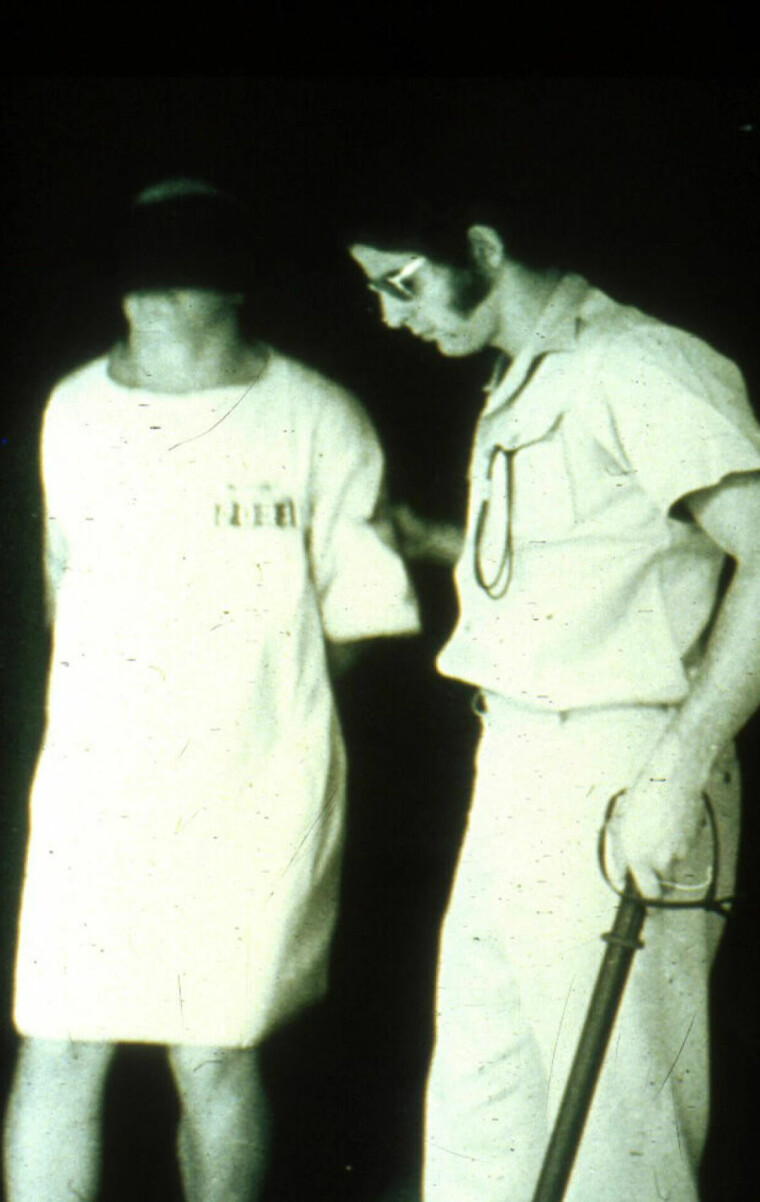

This was clearly demonstrated in the famous prison experiments of researcher Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues at Stanford in 1971.

Several students were locked in a cellar and given the roles of prisoners and prison guards.

The students who were the designated prison guards soon began to treat the student prisoners inhumanely.

Everyone seemed to turn evil if given the chance.

But later it turned out that the researchers had instructed the guards heavily on how to behave.

“I think that

we’ve been – and still are – in a replication crisis in psychology,” says

Halvorsen.

Researcher's own method always works best

Jan Ivar Røssberg is professor of psychiatry at the University of Oslo and a senior physician in psychiatry at Oslo University Hospital. He has conducted many psychotherapy studies and is well acquainted with the research in the field.

He also confirms the research problems.

“You have to look far and wide for studies where the researcher’s own beliefs don’t win out. I only know of one study where the researcher's own method ended up as the least effective one,” says Røssberg.

This situation is actually so unusual that this one study became known in professional circles precisely because it did not show that the researcher's preferred method was the best. We’ll return to this study.

But first: why is this the case? Why do researchers consistently find that their hypotheses are correct, while fewer than half of the results are confirmed if the same study is repeated?

Problem in the research culture

Let there be no doubt: Problems with the quality of research also affect other disciplines. Studies have shown signs of a replication crisis in both cancer research and economics, for example.

But Haeffel believes that the field of psychology has a particular problem in its research culture: that it has simply stopped using science to investigate causes and effects.

Hypothesis testing

Gathering knowledge can be done many ways, such as through in-depth interviews with patients. Haeffel is particularly concerned with the part of the research that deals with hypothesis testing.

In many fields, such as physics, biology and medicine, knowledge hunting typically takes place by setting up hypotheses – that is, models for how you think things are connected.

Researchers then carry out experiments or other investigations to test whether these models actually match reality.

The whole point of these tests is that they should also be able to show when hypotheses are not true. Such falsification – the ability to conceivably prove something false – is a hallmark of science.

Believes psychology has stopped testing hypotheses

Hypotheses are refined, changed or rejected based on study results. New knowledge builds on previous findings, and different hypotheses compete against each other. Eventually, the models that best explain reality will win out.

This method makes it possible to build increasingly precise theories about how phenomena in the world work. In biology, the theory of evolution has emerged, for example.

A lot of the research in psychology is not like this, however, Haeffel writes. Psychology has stopped using this scientific method as it should.

Publishing as many positive findings as possible

In many cases, the ideas in psychology cannot be falsified, making it impossible to set up tests that can show whether the ideas are wrong.

Haeffel writes that instead, the goal is often to publish as many studies as possible that show that the researchers' own hypotheses are correct, regardless of whether they provide greater insight or better treatment.

He believes this kind of a culture encourages bad research.

Manipulating the results does not have to be deliberate, but in reality it can still turn out this way.

Rigged for a positive outcome

Røssberg confirms that many studies are set up so that they have to produce positive results. One of the world's best researchers on depression has written a very good article on the topic, he says.

Røssberg refers to an ironic article by Pim Cuijpers and Ioana Alina Cristea, published in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences in 2016.

The researchers describe how to set up a scientific study to show that your therapy works even if it really doesn't. The fact box below provides the ‘recipe’.

Undermining psychology's credibility

The recipe for achieving studies with good results is taken to the extreme to make a point, namely that many psychology studies are designed in precisely this way.

The points in the recipe represent various bad research practices which together can produce studies with striking – but unreliable – results.

“We know from clinical research that low-quality studies tend to suggest a greater positive effect than high-quality research,” says Halvorsen.

He believes that bad research contributes to undermining psychology’s credibility as a science.

But here different researchers in the field are also in disagreement.

Many believe that the replication crisis is real and must be taken seriously, but there is no agreement on which methods are good enough.

The discussions surrounding the use of a waitlist as a control group are a good example of this.

Comparison is important

Researchers who study a particular type of treatment on humans need to have something to compare it to. For this they use a control group.

For example, a study can show that patients who receive a certain treatment get better. But is the treatment what is causing the improvement?

Patients might also have improved on their own or experienced a general placebo effect.

This is where control groups come in. By comparing the results in the two groups, the researchers can determine whether the treatment itself has had an effect.

Waiting list as control group

Most psychological studies compare the results of the treatment group with patients who are on a waiting list for the same treatment.

These studies cannot show whether part or all of the effect is simply due to the placebo effect, however. This could mean that we get a distorted picture of how well the treatment works.

The types of treatment we offer might in reality be far less effective than the studies suggest, according to Beth Patterson from McMaster University and her colleagues, after investigating the case in 2016.

This is part of the reason why researchers are so divided about how well psychotherapy works. Some researchers believe that waitlist studies should be included in assessing how well therapy works. Such summaries tend to show that a treatment is very effective.

Other researchers believe that the waitlist studies should not be included in the research summaries. Then the summaries show a more modest effect.

You can read more about the challenges of waitlist studies here.

Caption: Sverre Urnes Johnson is a professor and clinical psychologist at the University of Oslo and Modum Bad. (Photo: University of Oslo)

“I think the waitlist control method is setting the bar a little too low. Given what we know today, I would recommend using other types of control groups,” says Røssberg.

Can't stop there

Sverre Urnes Johnson is a professor and clinical psychologist at the University of Oslo and Modum Bad. He argues for awareness concerning the use of waitlists.

“Using the waitlist as a control group has its weaknesses, but the crucial factor is to compare the treatment group with something,” says Johnson.

He believes the most important thing is for researchers to be aware of how they use and interpret such studies.

“But we can’t stop there and claim that we’ve found the solution,” says Johnson.

“The next step is to put the theory into action and to set up a larger study where we compare the effectiveness of the best documented forms of treatment in the field. This means comparing active forms of treatment with each other.”

Need to set aside own treatment preference

This type of comparison does not always happen in psychology studies.

Testing one's own method against other forms of treatment can be sensitive and difficult for researchers, who tend to have strong faith in their own methods.

“Therapists often identify to a large extent with their particular methods. It requires trust on the research teams involved to set aside their preferred form of treatment,” says Johnson.

Because what if the results are worse than expected?

This is exactly what happened with a notorious article that did not confirm the researcher's hypothesis.

Shocking study results

Stig Bernt Poulsen and Susanne Lunn at the University of Copenhagen wanted to test the effectiveness of their own form of treatment – psychoanalytic therapy – on patients with bulimia.

This time they did not compare the treatment group with a waitlist control. Instead, they had the patients in the control group receive cognitive therapy treatment. The researchers who analysed the data did not know who had received which treatment.

The results came as a shock.

Only 15 percent of the patients who received psychoanalysis had stopped overeating and vomiting after two years.

In the group that received cognitive therapy, 44 percent had stopped the behaviours.

These were the results despite the fact that the control group had only received 20 hours of cognitive therapy over five months, while the intended therapy group had received weekly hours of psychoanalysis for two years.

Disappointing results are worth their weight in gold

Such results can turn out to be disastrous for the researchers who have put their theory to the test, especially when they do not get support from their colleagues.

Researchers who publish negative findings can quickly be regarded with contempt by others using the same form of therapy, says Røssberg.

For patients, these kinds of results are worth their weight in gold, because we gain more knowledge about what works and what doesn't.

“Publishing negative results is incredibly important for the field, even though it can be tough for the researchers who do it,” Røssberg says.

Haeffel points out that these are exactly the results that drive science forward.

He believes that the reluctance to accept negative outcomes is causing psychology to stagnate as a science.

More lousy research helps no one

Several researchers are calling for increasing awareness of what is happening in psychology research.

Svein Magnussen, professor emeritus in psychology at the University of Oslo, believes the key word is quality.

“My impression is that there are constant calls for more research. But nobody asks the question, ‘What about the research that is actually being carried out all the time – is the quality good enough? Are we asking the right questions? ’”

Most viewed

“More lousy research helps no one. I think we need better research,” he says.

It will get better

Røssberg still believes there is reason for optimism.

“We’re a little behind. But psychotherapy research is better today than ten years ago,” he says.

Røssberg and his colleagues are currently conducting randomized controlled studies to find out more about how different types of psychotherapy work.

He believes it is important to show how difficult this type of research is.

“Psychotherapy studies will never be as rigorous or optimal as drug studies,” he says.

In a drug study, you can give everyone the same pill. But in psychotherapy, the treatment is an interaction between the therapist and the patient. It can’t be standardized in the same way.

In the studies done by Røssberg and his colleagues, the researchers review video recordings of thousands of therapy sessions to see what the therapists actually do.

“I think a lot of people who comment on how studies in psychotherapy should be done haven’t tried it themselves,” he says.

“It’s incredibly difficult to do these studies. I like to say that before I did a randomized controlled psychotherapy trial, I was also tall and dark.”

“After carrying out some studies, I’ve become fat and bald.”

Photos:

All photos from The Stanford Prison Experiment: PrisonExp.org.

Blue illustration: Yiucheung/Shutterstock/NTB

References:

Gerald J. Haeffe: Psychology needs to get tired of winning. Royal Society Open Science, June 2022.

A. M. Scheel, et al.: An Excess of Positive Results: Comparing the Standard Psychology Literature With Registered Reports. SAGE Journals, April 2021.

Open Science Collaboration: Psychology: Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, August 2015.

J. P. A. Ioannidis: Most psychotherapies do not really work, but those that might work should be assessed in biased studies. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, October 2016.

B. Patterson, M. H. Boyle, M. Kivlenieks, M. Van Ameringen: The use of waitlists as control conditions in anxiety disorders research. J Psychiatr Res., December 2016.

J. A. Cunningham, K. Kypri & J. McCambridge: Exploratory randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of a waiting list control design. BMC Medical Research Methodology, December 2013.

T. A. Furukawa, H. Noma, D. M. Caldwell, M. Honyashiki, K. Shinohara, H. Imai, P. Chen, V. Hunot, R. Churchill: Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, September 2014.

S. Poulsen, S. Lunn, S. I. F. Daniel, S. Folke, B. B. Mathiesen, H. Katznelson, C. G. Fairburn: A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, January 2014.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no