The theoretical foundation for psychology is shaky. No one knows if the the theories are valid

As a therapist, you need to be ready to abandon the method you know and like if it doesn’t make sense for the patient, according to researcher Andreas Høstmælingen.

Something is wrong with psychology.

Different therapists might give a patient completely different explanations for their problems, often with great conviction.

In another article in this series, Dag Wollebæk relates how psychologists suggested countless theories as to why he had a difficult time during his years in psychotherapy.

“The theories run the gamut,” he says.

What do psychologists actually base their explanations on?

The interpretations stem from a number of theories about how the mind works. The only problem is that no one knows which of the theories – if any – match reality.

Some researchers believe that psychology is in a theoretical crisis, and one that is much deeper than the replication crisis, which you can read more about here.

A shaky foundation

The theoretical foundation for psychology is shaky, according to researchers Markus Eronen and Laura Bringmann in an article from 2021.

That statement might sound a bit academic and remote from our daily lives.

However, these theories wield a strong influence not only on the psychologist’s couch, but also on how we think about ourselves and what society perceives as normal and sick.

Once upon a time, for example, American women risked ending up in a mental asylum if they were too outspoken and independent, according to a Time magazine article.

Society is permeated with ideas derived from psychological theory. But we don't actually know if these theories are true, according to several professionals interviewed by sciencenorway.no.

Overarching theories that explain the world

Eronen and Bringmann compare the field of psychology with other branches of science.

If you hear about theories in biology or physics, such as the theory of evolution or Einstein's theory of relativity, you can count on several things.

Many, possibly thousands, of studies have been carried out to test whether the theory is really true. The studies build on each other and provide an overall explanatory model that becomes increasingly precise over time.

This model explains the underlying causes of phenomena, so you can use the theory to predict what will happen.

But in many parts of psychology this is not the case, Eronen and Bringmann write in the scientific journal Perspectives of Psychological Science.

Just floating around

New theories are constantly being developed in the field of psychology, but they do not build on each other or become either confirmed or disproved. Instead, they just float around for a while, until eventually they are abandoned or forgotten, the researchers write.

Similar criticisms have appeared in several scientific articles in recent years.

Andreas Høstmælingen is a clinical psychologist and head of research at the Norwegian Center for Child Behavioral Development (NUBU).

He concurs that the theories in psychology differ from many other fields.

Heaps of theories – and no one knows if they’re valid

“Psychology's thinkers never formulated theories that could be integrated into a coherent whole,” Høstmælingen wrote in Psykologtidsskriftet, the journal of the Norwegian Psychological Association, earlier this year.

Instead, multiple different directions emerged, such as cognitive and psychodynamic theory. Everyone had their different, and often incompatible, explanations of how the mind works.

“We haven’t been able to reconcile these theories,” says Høstmælingen.

Nor have researchers been able to determine whether any of them are objectively correct.

“No one has shown that some of the theories are more valid than others,” Høstmælingen writes.

Tales in the therapy room

Nevertheless, these theories are used very actively in therapy sessions.

This is precisely what distinguishes psychotherapy from other conversations. The therapy contains a specific theoretical explanation for why the patient has psychological problems and a specific model for how the treatment should work.

The theories are thus used to create a meaningful narrative about how the problems work and how they should be resolved.

But – as Wollebæk experienced – these narratives can run the gamut, depending on which psychologist you go to.

Lack of self-realisation – or defence mechanisms?

Høstmælingen describes an example in the journal Psykologtidsskriftet.

One of the theories – humanistic-existential theory – states that humans are motivated by self-realisation. Psychological problems arise when we feel we’re not the way we think we should be.

The treatment involves creating a situation that enables the patient to create personal growth more successfully.

Psychodynamic theory, on the other hand, says that mental disorders occur when healthy emotions – such as anger or sexual desire – trigger negative emotions like anxiety, shame or self-blame. The theory holds that we develop defence mechanisms to avoid internal conflict, Høstmælingen writes.

Treatment consists of managing the defence mechanisms and preventing negative emotions from accompanying the positive ones.

Neither of these explanations offers clear evidence for being the actual cause of psychological problems.

Disease mechanisms not understood

“These statements are just metaphors in a lot of ways,” says author and clinical psychologist Jørgen Flor.

“We don’t understand the disease mechanisms behind mental illness.”

We know that psychotherapy is helpful for some patients, which is quite well documented, but we don’t understand that much about why it works.

We often look at mental illness through a medical lens. Medical conditions often have underlying disease mechanisms that cause symptoms. The aim is to treat these mechanisms, if we can.

But in psychology, researchers have not been able to find such underlying causes. We don’t know what the treatment is actually working on.

Educated guesses

Flor describes the theories in psychology as educated guesses.

So does Joar Øveraas Halvorsen, a clinical psychologist and associate professor at NTNU.

“There are so many theories. In some cases, a good deal of basic research underlies them. But I think a good number of theories are just a good idea or an educated guess.”

However, he points out that psychology is not necessarily alone in this. Medicine has some theories that are not particularly well documented either.

But is that so dangerous? Does it really matter whether the explanations and theories are correct if they help people?

Useful stories

In many cases, the theories can be useful, regardless of whether they are correct.

A strong belief in the theory and method can make the therapist more secure and more convincing, which in turn affects the patient. Research has shown that treatment success depends on the patients' trust in the therapist and confidence in the method.

The therapist listens to what the patient shares and uses their theoretical understanding to offer an explanation for what is creating the problems and keeping them going, says Høstmælingen.

“The psychologist offers an interpretation of the situation and a strategy to resolve the problem,” he says.

The theory can help create a meaningful narrative that the patient and the therapist can use to figure out the best way forward.

What if the patient feels the treatment is not right for them?

Not like a diabetes diagnosis

If your doctor looks at your blood sugar readings and says you have type 2 diabetes, you probably do, regardless of how you feel – even if you find the diagnosis paradoxical because you are fit and have a healthy lifestyle.

The diagnosis tells you that too much glucose is circulating in your blood because the cells are unable to absorb enough blood sugar after a meal.

These are objective facts, based on a large amount of research that has established, refined and confirmed theories about the mechanisms of action behind diabetes.

It’s not like that at the psychologist's office.

Patients decide whether theories are true

“The theories in psychology are not objectively true. They become true when a patient can use them to create change,” says Høstmælingen.

The value in the theories therefore only arises when the theory creates a meaningful narrative for the patient.

“A key part of the practice is to check with the patient: ‘Does this make sense to you? Can we agree on this explanation and try out strategies based on it?’”

Have to change treatment that doesn’t make sense

“Often the patient might say, ‘Yes, let's try it out’,” says Høstmælingen.

And if this works and the patient experiences progress, then it’s a good strategy.

Most viewed

But if the patient feels that the treatment doesn’t fit, that it doesn’t agree with their own perception of the world or their psychological problems, then something should be changed.

“A lot of treatment methods aren’t that rigid. They can be adapted to patients’ individual needs,” says Høstmælingen.

However, sometimes the method as a whole doesn’t make sense for the patient. As a therapist you have to consider whether the patient should try a completely different type of therapy.

Working together to find treatment that helps

“There’s a paradox here,” says Høstmælingen.

“As a psychologist, you have to learn theory to become good at relating to people and offer an explanation for their psychological problems. But at the same time, you have to be ready to abandon a method you know and like if it doesn’t make sense for the patient.”

Høstmælingen believes that mental health services should be set up to allow for good opportunities to try things out until the patient finds a treatment that feels right.

“We need to stop thinking that a treatment is wrong if a method doesn’t work for a patient or that the patient is resistant to treatment. The idea is to start a process in order to arrive at something that works,” he says.

Power imbalance

Høstmælingen does not believe that such a strategy is typical in today's services for the mentally ill.

Patients might not have as much influence on how the disease is interpreted as they should.

Wollebæk states in another article in this series that he believes patients are often not in a position to question the therapist's explanations.

“There’s a power imbalance where you as a patient are at your most vulnerable. You’re confronted with someone holding a lot of authority who gives you an explanation,” he says.

Does treatment sometimes fail because patients don’t know that they can and should challenge this authority when the theories don’t make sense?

The power of psychology

The theories of psychology also have an influence far beyond the therapy room.

We actively use concepts and theories from psychology in our everyday language and often regard them as truths.

We might for example think that other people's actions are expressions of unconscious desires or say that someone's behaviour is a defence mechanism. We do this without reflecting on the fact that 'unconscious desires' and 'defence mechanisms' are theories from the field of psychology.

Nor do we consider that these ideas are not necessarily objectively true at all.

We can find many historical examples of ideas that have gained great influence, only to recognise later that they don’t hold water. Some of them have done a lot of damage.

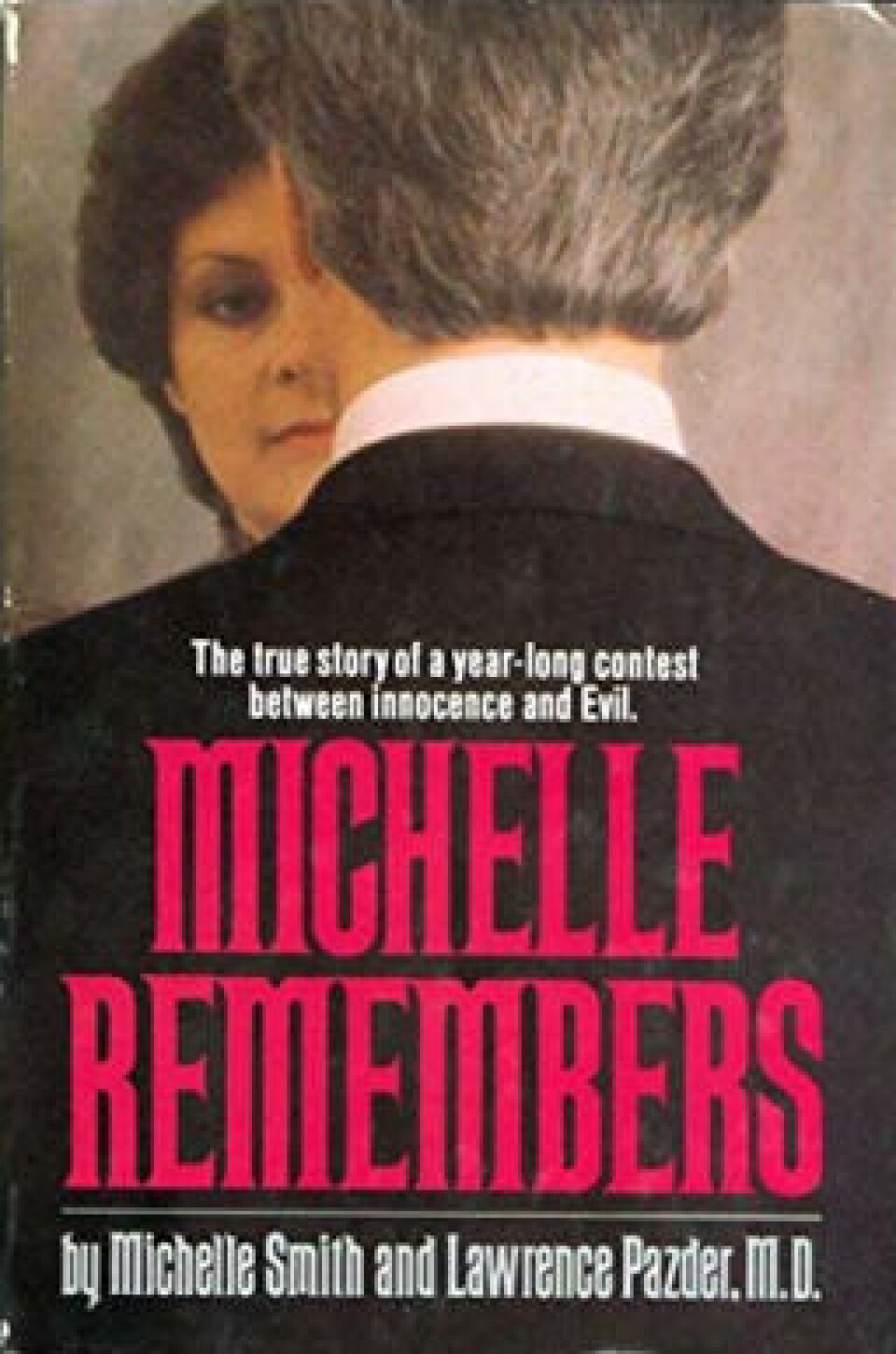

Sensational abuse

A few decades ago, a number of American patients and their families were traumatised by their therapists.

In their psychology sessions, the patients suddenly ‘remembered’ dramatic abuses from their childhood that they had apparently repressed.

The idea soon leaked out of the therapy room and quickly spread in both the United States and Europe.

Forgotten murder?

Suddenly we knew that, in principle, anyone could have experienced horrible things, without remembering anything. Or we ourselves might have committed barbaric acts. In some cases, these 'recollections' had major consequences

The notorious Birgitte Tengs case is one such example.

Tengs’ cousin insisted that he could not remember killing his cousin. But investigators said he could have repressed the memory, and eventually they managed to convince the boy that he must have committed the murder but then forgotten about the incident.

It has been shown since then that this phenomenon probably does not exist. You can read more about the topic in another article in this series, Psychology folklore or science? Uncovering facts about repressed memories.

Theories create reality

Henrik Berg has a background in psychology and philosophy and works as a professor at the University of Bergen.

He believes we should be very aware that psychology has a very special role in society.

“Psychology doesn't just represent the world, it intervenes,” says Berg.

In other words, the psychological theories are not just a description of what we believe to be reality. They create reality.

When we perceive the theories as truths, they contribute to how we see ourselves and interpret what happens around us.

“This means that you have to be extra careful as to what types of descriptions of people and suffering you accept and send out into society,” says Berg.

Mothers blamed

Poorly founded theories can have major negative consequences.

“You can find imaginative descriptions and assumptions about disease mechanisms that can be extremely harmful,” says Berg.

“Within the psychodynamic school, which was dominant for a long time, it was thought that autism was caused by emotionally cold and insensitive mothers. This of course caused mothers an incredible amount of pain.”

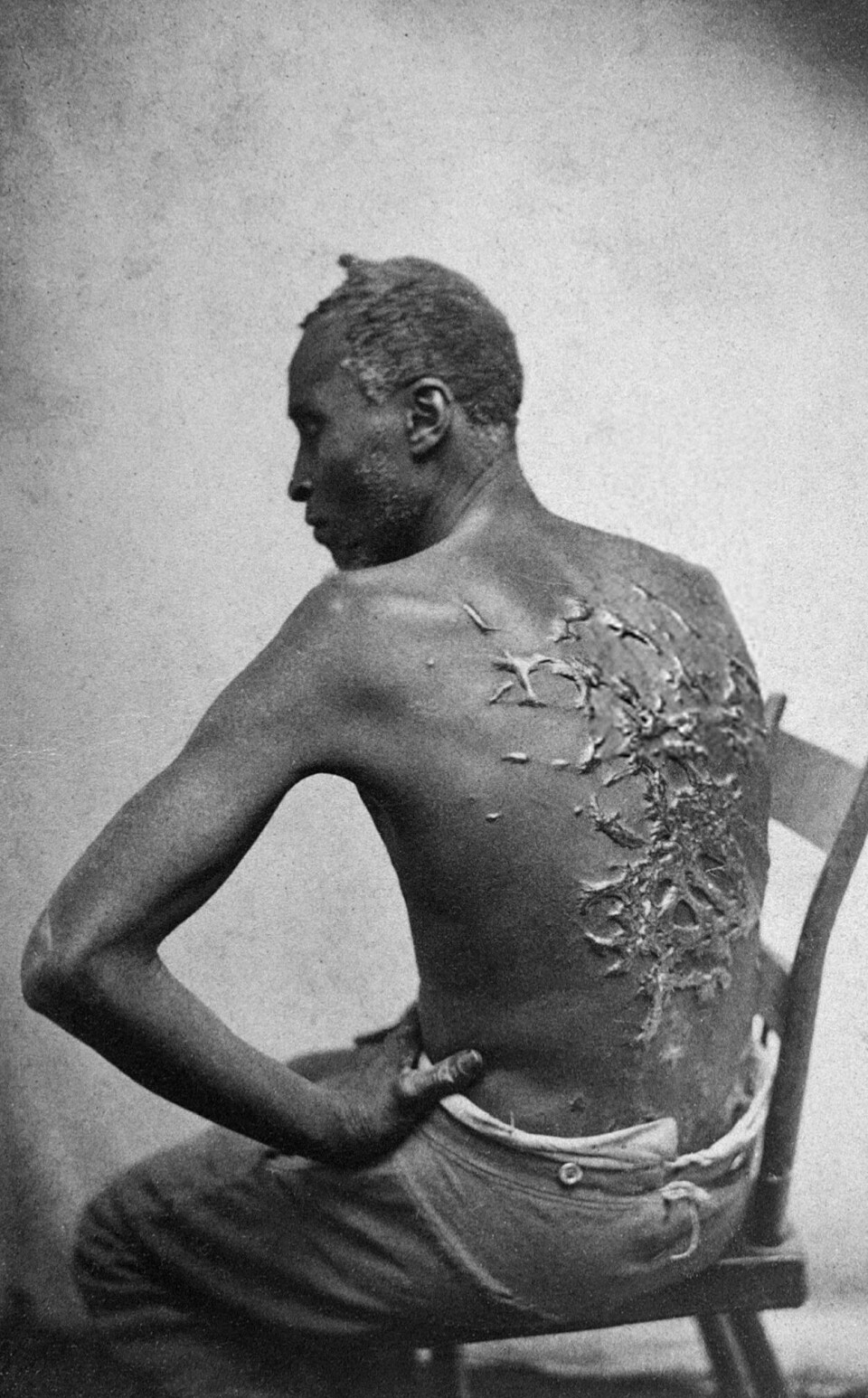

Even further back in time, we find serious examples of how ideas from psychology contributed to maintaining and justifying societal atrocities.

Runaway slaves

At the end of the 19th century, a supposed mental disorder called drapetomania – the overwhelming urge to run away – was rampant in the southern states of the United States. The disease caused slaves to escape from the plantations, Berg writes in his Norwegian book Evidens og etikk (Evidence and ethics).

The hypothesis behind the diagnosis was that slavery was such an improvement in the slaves' lives that they had to be mentally ill to want to escape.

The idea no doubt sat well with the plantation owners who fought to maintain slavery and who certainly used the treatment against the alleged disease: whipping for slaves who seemed restless.

Today we might laugh at this absurd idea if it were not so tragic.

Reflects culture of the time

Perusing old truths in various fields, you find a lot of strange things that do not only apply in psychology.

However, we may need to be extra vigilant in this field.

Eronen and Bringmann believe that compared with a number of other fields, psychological theories are built more on ideas and educated guesses than on objective facts and documented mechanisms of action.

Psychological theories are more vulnerable to trends and currents in the zeitgeist. To some extent, they become mirror images of the culture and morality of the time. In this way, they can also reinforce prejudices and justify unfortunate attitudes.

Homosexuality was classified as a mental illness until 1977 in Norway, for example.

Concepts we have no idea about

Jan Ketil Arnulf is a psychologist and professor at BI Norwegian Business School.

He believes that psychology has become somewhat skewed.

“We’ve introduced a whole series of concepts and ideas and we really have no idea what they are: motives, thoughts, attitudes, viewpoints, dreams – in short, everything that constitutes the soul.

“Today we take them for granted, but we don't know what they are. There’s no documentation that they’re correct,” he says.

Arnulf uses an example from the past to illustrate.

Patricide and patriotism located in the brain

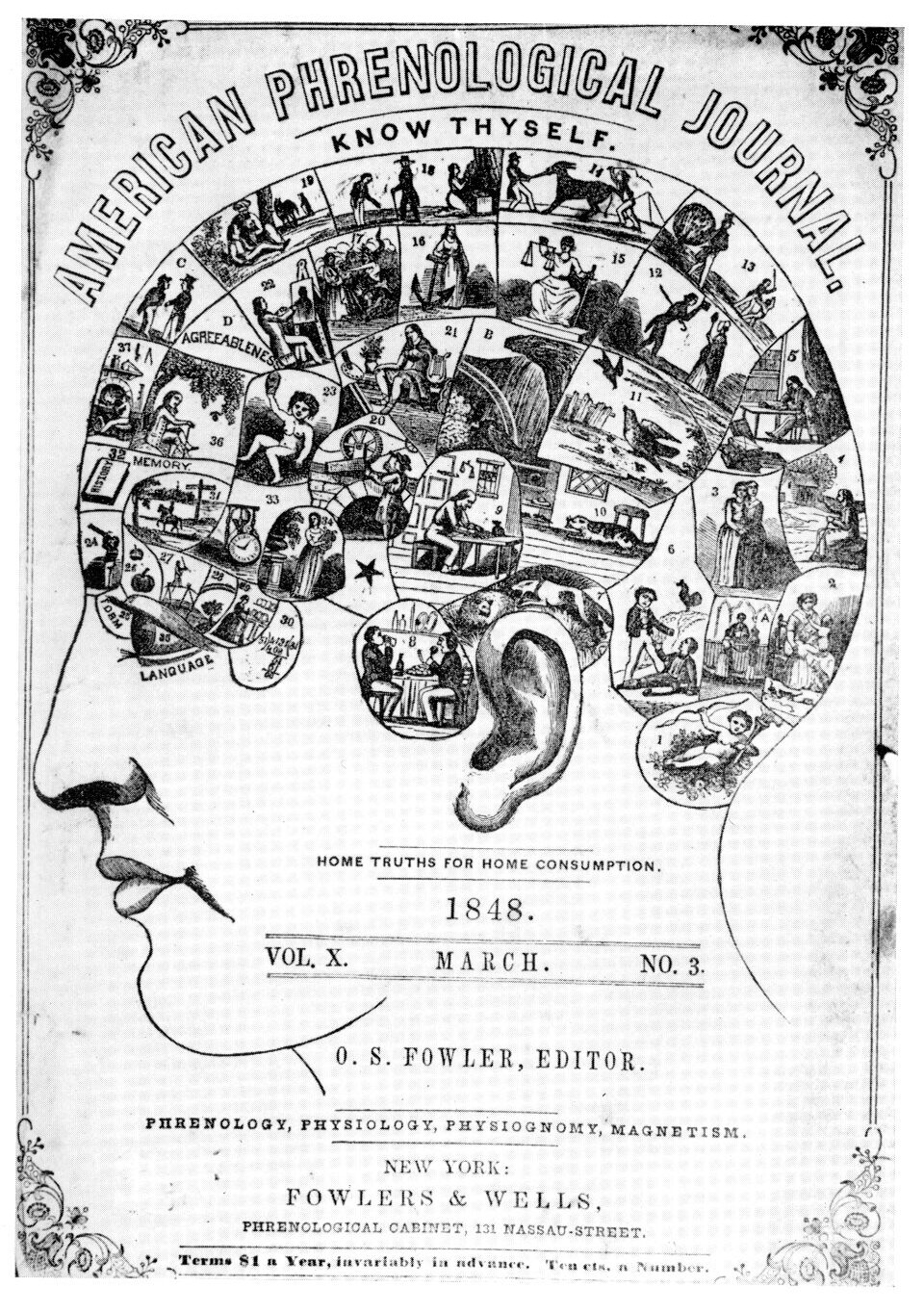

“The psychology in the 19th century included a concept called the phrenological map of the brain,” he says.

Phrenology is an outdated idea that the shape of the brain can reveal something about people's characteristics and abilities. The researchers of the time measured bumps and pits in the skulls of various people and linked the shape to mental traits.

Psychologists could examine someone who had murdered their father, for example, and thus find the centre for patricide. In the same way, they found different centres of love for children, for spouses and for the fatherland.

Projected ideas of the time

“What we see today is that they simply took the description of a 19th-century, bourgeois, German-speaking person and projected it onto the brain.

“Today it seems comical. But what isn’t so comical is that we continue to project things that we’re not sure are there.”

Arnulf believes that a lot of psychological research has stagnated. In 2022, he and colleagues published a study that suggests just that.

In reality, scientists only divide the world into new categories that they have created, without getting any closer to answering what really goes on in the mind, says Arnulf.

Critical thinking is important

Berg believes that researchers have to be aware of the uncertainties in the psychological theories.

What blind spots do we have today?

What ideas do we now consider to be natural and true that might be refuted and abandoned in the future?

They might be almost impossible to identify from our standpoint in the middle of our own time. But we need to try to find them, says Berg.

“In science, and perhaps especially in psychotherapy research, developing a critical sense is incredibly important.”

He wants to hold the experts accountable.

“Scientists have to maintain a critical distance from the positions that they hold at all times,” he says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no