The paradox of diagnosis: How labels impact the mental health of adolescents

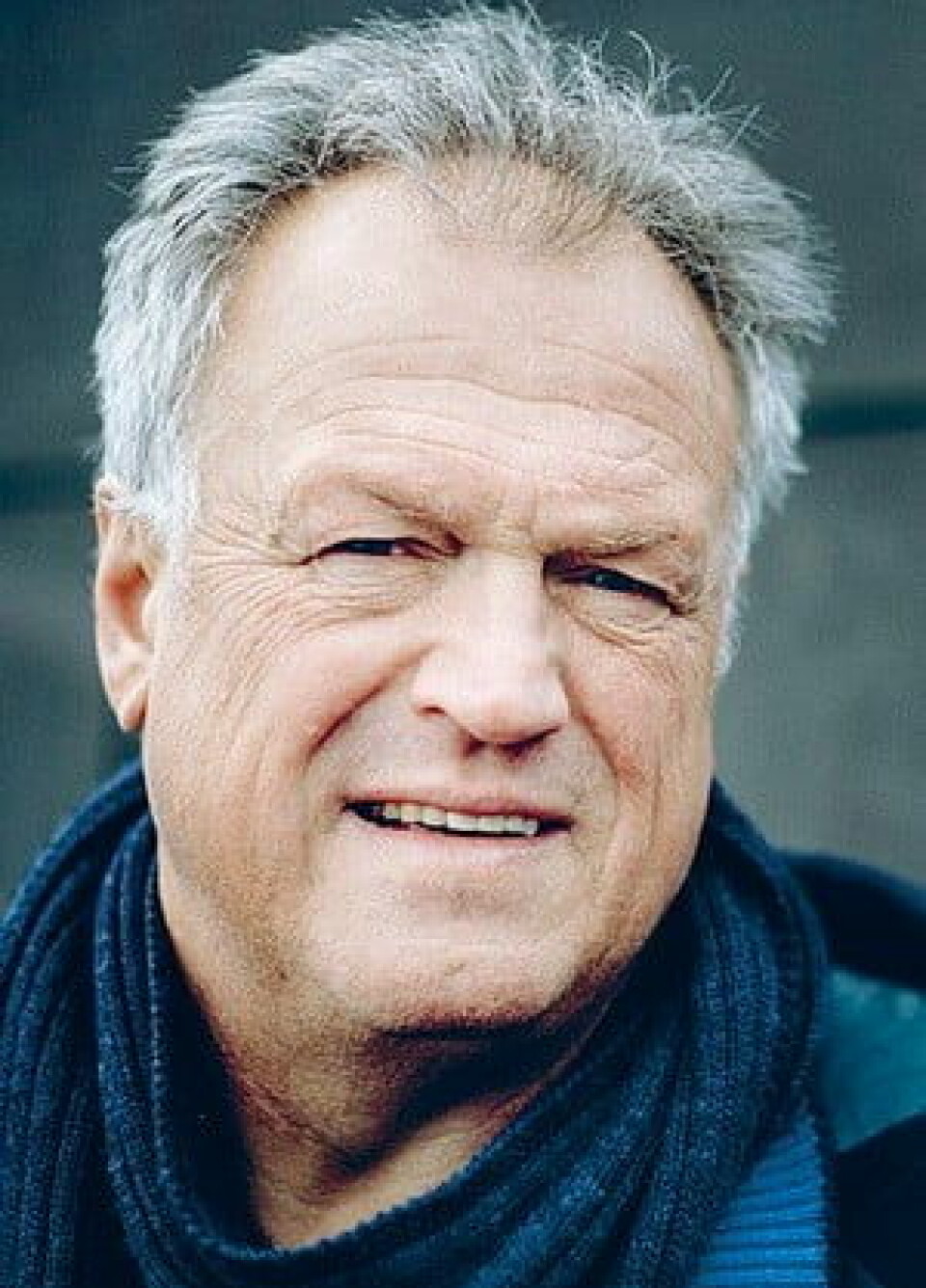

An entire generation of young people is being labelled as sick. Adult culture should instead protect young people's space so that they have time to find themselves, clinical psychologist Per Are Løkke believes.

Per Are Løkke has worked with young people for over 30 years.

He and psychologist Ida K. Holt have now co-authored the book Håndbok for ungdom med vanskelige foreldre – og for foreldre som vil lære av barna sine (Handbook for young people with difficult parents – and for parents who want to learn from their children).

Løkke tells sciencenorway.no that he has observed a noticeable change over the years that he has welcomed young people into his therapy space in Nesodden, Eastern Norway.

A questionnaire and quick diagnosis

The teenagers have first been to their GP, other healthcare providers, or they might have looked up information on the internet.

There, they receive a quick diagnosis which establishes that they have a mental disorder.

The diagnosis may have been made after the teenager completed a questionnaire with around 20 questions about symptoms. Healthcare professionals, who often work under tight time pressure, then refer the young person to a psychologist.

Once they come to Løkke’s office, they often ask what the psychiatric diagnosis they have received actually means.

Concrete problems

That’s not an easy question to answer, says Løkke.

“On their own, general diagnoses like anxiety and depression are meaningless,” he says.

After one or more sessions, Løkke usually determines that the youth’s problems are tied to specific life circumstances. These could relate to events from their upbringing, or to current situations involving conflict with parents, friends, or school.

“Or the issue could stem from unfamiliar and emerging aspects within themselves," he says.

He explains that the adolescent period of life brings challenges in many different arenas that require teens to find solutions.

“Teenagers are vulnerable individuals. They may struggle with love, sexuality, their own identity, performance pressure, or difficult ties with their parents,” he says.

The terminology of symptoms tells young people who they are

Løkke believes that young people today are given too little opportunity to get to know themselves.

“Being young is a journey of discovery. You are supposed to discover both yourself and life,” he says.

Løkke says adults need to take the time to listen to what young people have to say.

Now that there is so much focus on symptoms and diagnoses, we tend to spend our time counting symptoms rather than listening to their stories.

He believes this symptom-focused thinking has spread to all levels of society and has entered our everyday language.

It tells young people who they are before they have figured it out for themselves.

25 per cent have a high level of mental distress

Around 7 per cent of children aged 4 to 14 have a mental disorder, according to a report from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) (link in Norwegian).

Even more children and adolescents self-report in surveys that they have mental health problems. Much of it revolves around anxiety and depression.

At the lower secondary school level, 25 per cent of girls report having a high level of mental distress. In upper secondary school, the number is 29 per cent.

Among boys, 9 per cent in lower secondary school and 12 per cent in upper secondary school report having mental health problems, according to NIPH.

Studies have shown a particularly strong increase in self-reported mental distress among girls in the last 10 to 20 years.

Identity becomes linked to the diagnosis

Pathologising and treating young people who are struggling simply because they are young – and not because they are sick – can do more harm than good, Per Are Løkke believes.

If a diagnosis is made too early, young people may link their identity to this diagnosis. They are not given the time and space to find their own identity.

Most viewed

“The tendency to diagnose is making an entire generation of youth sicker, as well as individual children and adolescents. Young people should be left alone,” Løkke says.

He points out that diagnosing young people can tie them to their parents even more, often because the parents are afraid that something bad will happen to their children.

“It’s a positive thing that parents and adults today have become more involved in young people's mental health. But the problem is that during adolescence, you are supposed to start seperating yourself from your parents. That is their time to find their own role and place in society. When a young person receives a diagnosis, this whole process can be put on hold,” Løkke says.

Restricts life's potential

Farhan Shah, a philosopher and researcher at the Faculty of Theology at the University of Oslo, writes in an op-ed on psykologisk.no that it is time to realise that a focus on diagnoses is a dead end.

Diagnoses focus on deficiencies and illness – so not what you can do, but what you can't do. Extensive use of diagnostic categories restricts life's potential and limits the resources we have within us and around us, he writes.

“We need to talk more about the existential drama that is life – about how we face pain, loss, betrayal, anxiety, but also the possibilities for recovery, for solidarity, and care. We simply need to practice tolerating uncertainty and embracing imperfection, without methodical approaches that perpetute an artificial divide between ‘the sick’ and ‘the healthy’," he writes.

Turning normal into sick

Catharina Elisabeth Arfwedson Wang is a professor of clinical psychology at UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

She believes that we have started to turn life's pain into illness.

Wang reminds us that having symptoms of anxiety and depression is not abnormal for humans. It is, in fact, actually necessary.

“The problem is that our culture tends to interpret these entirely normal symptoms as illness. There’s almost an expectation that life should only consist of sunny days. But the dark days can be just as important. To see the light, we also have to experience darkness,” she says.

Especially in countries with high living standards, we may have lost touch with what life is really about. Wang believes we have unrealistic expectations of a life without pain and discomfort.

Anxiety and depression are normal

Wang is interested in the evolutionary perspective in psychology that explores how humans and our psyche have evolved over thousands of years.

This perspective can make it easier to see that symptoms of both anxiety and depression serve a function.

Wang has previously written about this in the Norwegian journal Psykologtidsskriftet (link in Norwegian).

“Life gives us stress, difficulties, and pain. This is something humans have lived with throughout history, in all cultures. We all experience symptoms of anxiety and depression. It’s normal and can serve a useful function,” she says.

“We know from research that depressive reactions can be a way of withdrawing when you no longer have sufficient resources to cope with the challenges you're facing. You’re also signalling to your flock: ‘Now I need help’.”

We compare ourselves to others

As social animals, humans support each other. But we are also always in social competition with others in our group. We fight to secure our place.

Today, we compare ourselves to people who are well outside our social community, and this can easily trigger an experience of failure, according to Wang.

Wang believes that the extensive use of social media by today's youth makes it easy for them to compare themselves with a wide array of people, some of whom may not be suitable benchmarks. This behaviour can affect their mental health.

A common phrase that many young people hear from adults is that they ‘can become whatever they want’.

Wang is not sure this is something that young people actually want to hear from adults.

"It can be overwhelming and too much responsibility for adolescents to bear. The framework for both identity and self-esteem can become too indefinable,” she says.

Our genes can't keep up

Wang believes that an evolutionary perspective can help us explain the increase we see in mental health problems in many parts of the world.

In modern times, everything around us has changed very rapidly. But humans – our bodies and our psyches – are almost exactly the same as they were thousands of years ago.

“The development has happened too fast for our genes to keep up,” Wang says.

The psychology professor compares the apparent epidemic of mental health problems with the obesity epidemic that we are also experiencing.

“Our bodies aren’t adapted to the abundant access to food we have today. At the same time, we’ve become less physically active, leading to the development of obesity, diabetes, and other physical ailments,” she says.

Our mental health is also impacted by the fact that modern society is very different from the society in which our ancestors lived.

“Previously, people lived in small, manageable environments. They lived within their own small group and found their place there. The connection to family and those closest to them created the foundation for this security," Wang says.

But today, many no longer have the experience of belonging to a group where we are loved and wanted. A place where there is a need for us, according to Wang.

She believes that in order to prevent an increase in symptoms of anxiety and depression in the population, we should focus our efforts on giving people a sense of belonging and being able to contribute in smaller social communities.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no