Psychology folklore or science? Uncovering facts about repressed memories

Psychological theories that have become truths in our culture may be built more on naive belief than on science, according to researchers.

“Oh God, the dentist appointment! I’ve completely repressed it!”

Many ideas and theories from psychology have become part of everyday language. A part of how we think about ourselves.

But what happens when these ideas turn out to be ill-founded?

Some of the psychological theories that have spread and become truths in our culture are built more on naive belief and psychological folklore than on science, according to Svein Magnussen.

This can lead us down the wrong path.

Magnussen is professor emeritus at the University of Oslo and one of Norway's leading experts on eyewitness testimony.

Repressed memories

An idea that has had significant consequences in society is the theory of repressed memories.

Like many ideas in psychology, it can be traced back to Freud, the father of psychoanalysis.

In his book The Interpretation of Dreams from 1899, the Austrian psychotherapist wrote that we humans repress forbidden early fantasies.

Most of the time, it's about sex.

Fantasies become real memories

“Freud, for example, has an idea that little boys are sexually attracted to their mothers,” Magnussen says.

“Then the boys realise that this is forbidden and will have social consequences. And so they repress these forbidden fantasies.”

Freud believed that dreams, through some unconscious process, were banished to the subconscious, a part of the mind that we normally do not have access to. The idea has been debated ever since.

But in the 1980s, something strange happens.

“Suddenly

it's no longer about fantasies, but actual experiences,” Magnussen says.

He believes the starting point for this new idea was a lecture by psychologist Judith Herman in 1980. She argued:

If our memories are painful and traumatic enough, they can simply be repressed, so that we have no idea they are there.

Sexual abuse

The idea of repressed memories coincided with an important shift in society. By this point, there was finally a growing awareness that many children have experienced sexual abuse.

And it was typically such memories that psychologists believed were repressed into the subconscious.

But therapists believed that the experiences still surfaced, in the form of a variety of different psychological and physical ailments.

The treatment involved bringing the memories back to the surface through psychotherapy. Often in the form of techniques such as hypnosis, psychodrama, or dream interpretation.

Satanic panic

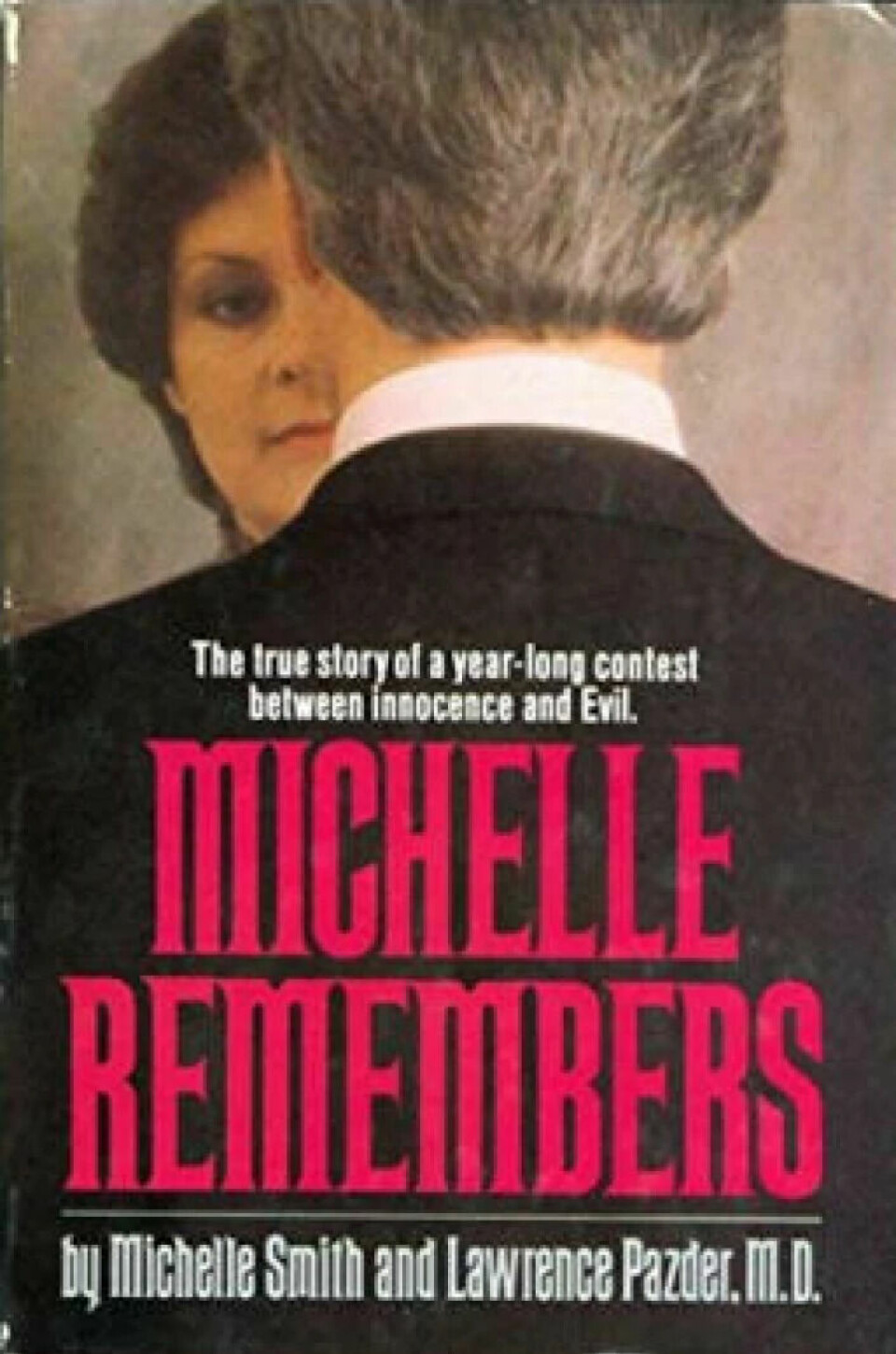

“The idea appeared out of nowhere and spread like wildfire,” Magnussen says.

In the United States, many psychotherapists specialised in retrieving repressed memories of abuse, and soon stories began to circulate both in therapy rooms and in the media.

The retrieved memories were often extremely detailed and vivid. And horrifying.

It was often not just about abuse, but about nightmarish events with satanic sacrifices, torture, and ritual abuse.

Witch hunts

This developed into a moral panic with thousands of alleged cases of satanism and organised abuse. Families were torn apart by accusations and distrust.

The phenomenon also spread to other countries. Experts argued that the repressed memories could be so unbearable that the patient's personality split into many parts.

“It was an epidemic in the ‘90s, almost like witch hunts,” Magnussen says.

But at the same time, significant scepticism grew, especially among researchers who study how memory works.

Doesn’t add up

It is of course very important to take reports of abuse seriously. It can often be difficult to come forward with such information, and traditionally the victims were often not believed.

However, there is reason to be sceptical of crystal-clear memories that suddenly appear, especially in a situation where one is specifically digging for such memories.

“It doesn’t align with any empirical evidence,” Magnussen says.

The ideas about repressed memories were not based on research and scientific documentation, according to Magnussen.

“It was based on psychologists' interpretation of what happens in the therapy room.”

“All research shows that you actually have a particularly good memory for unpleasant, dramatic, and traumatic memories.”

Painful memories tend to linger

In 2019, Magnussen and two colleagues wrote about this topic in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association (link in Norwegian).

Studies of war veterans and victims of torture, terrorist attacks, and abuse show that traumatic memories stick, and that painful experiences are remembered better than everyday events, they write.

“It’s not necessarily the case that you think about such memories all the time, but if you are asked, you know they are there,” Magnussen says.

He says that studies have been conducted among people with confirmed childhood abuse. When they are asked about various childhood incidents in adulthood, most remember the abuse.

False memories

Magnussen believes there were often completely different explanations for the memories that were evoked in therapy rooms.

Most viewed

“In many cases, the memories were likely false,” he says.

Research has shown that our memory can be molded and changed afterwards. It is not that hard to get people to remember events that never happened.

Some of the methods used to retrieve forgotten memories are particularly effective at creating such false memories.

Even in

cases where real memories do actually reappear later, there are other

explanations than unconscious repression.

In some cases, children may have experienced events that they did not realise were abuse at the time. When the memory randomly resurfaces later in life, the person sees the matter with adult eyes and realises that it was abuse.

It is also natural to forget details or to consciously try to forget parts of painful events.

The idea lives on

A summary of research from 2021 concludes that there is a lack of scientific documentation for the existence of unconsciously repressed memories.

But despite this, the idea continues to live on among both psychologists and the general public, the authors write in another article.

Magnussen confirms that this is also the case in Norway.

He and his colleagues have conducted several surveys among Norwegian psychologists. In 2012 and 2015, almost half believed that repressed memories existed. International overview studies show the same.

Some researchers, like Chris Brewin from University College London, believe that such studies paint a misleading picture. That is because many therapists today have a different understanding of what repression means, and many agree that one should not use suggestive techniques to elicit forgotten memories.

Other researchers argue that much of the old understanding still lingers.

We do not know if people are lying

Magnussen believes that such belief in poorly founded ideas can have unfortunate consequences, including in the legal system, which is his own field of expertise.

For example, he says that both judges and experts in court cases have believed theories that our behaviour shows whether we are lying or telling the truth.

“There’s a long tradition of naive psychological theories that liars behave in certain ways. That they avoid eye contact and are restless in their bodies.”

“But that's just nonsense. We have 50 years of research showing that it’s not true. There are no reliable non-verbal signs of lying and deception.”

Behaviour says little about credibility

Nevertheless, such ideas continue to live on and probably influence our decisions.

A Norwegian study, for example, examined how police investigators perceived a rape victim’s witness statement. It turned out that they considered the victim more credible if she expressed the expected emotions, such as sadness and despair.

At the same time, other studies show that it is not the case that rape victims behave in special ways during questioning.

“There’s no correlation between how you present yourself and what has actually happened,” Magnussen says.

“We have ideas about how you should appear that do not align with reality.”

Trouble in court cases

The idea of repression has also led to problems, according to Magnussen.

“The police still receive reports from people who remember something they were supposedly subjected to when they were one year old. It’s completely meaningless,” he says.

The idea of repressed memories also played a significant role in the highly criticised Birgitte Tengs investigation.

The suspected cousin insisted that he could not remember killing his cousin. However, the investigators explained that the brain could form a barrier against painful memories.

“They offered an explanation that you might have repressed it,” Magnussen says.

In the end, the cousin became convinced that this must have been what happened and made a confession that later turned out to be false. Today, another man has been convicted for the murder that the cousin was accused of. The man has appealed the verdict.

Therapy can also harm

Jørgen Flor is a specialist psychologist and author of the book Skadelige samtaler (Harmful conversations).

He believes it is important to be aware that therapy can have a strong impact, also in a negative direction. In such cases, you can cause harm instead of helping, for example, in trying to evoke forgotten memories.

“I think that if you’ve forgotten sexual abuse, that’s fine. There’s no reason to dredge it up again if you’re not experiencing symptoms or problems.”

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.