The unknown wartime merchant seamen:

Michael, a Briton, was 14 when he was killed on a Norwegian ship

30,000 foreign merchant seamen worked for Norway during the Second World War.

Michael Goulden from the United Kingdom had gone to maritime school for six months before he enlisted as a galley boy on D/S Augvald. The fourteen-year-old had to have written approval from his parents.

He was one of many British boys who worked on Norwegian ships during the war. This was considered civilian work, which made it legal to employ young people under the age of 18.

On board, they did the same job as the adults.

When Michael died

D/S Augvald was carrying steel and tractors when it joined other merchant ships in a convoy from the USA in February 1941. Michael served food and cleaned the ship's canteens.

The weather was bad, and during a storm, the Augvald lost contact with the other ships. A German submarine appeared out of the depths. Its torpedo hit the front of the ship, and the Augvald sank in just a few minutes.

Only one of the 30 people on board survived. Sailor Rasmus Kolstø jumped into the water and got onto a raft, according to the maritime inquiry. Around him, people shouted for help. He tried to paddle over to them, but couldn't make it. After a while the screams died away, and Rasmus was alone in the dark night.

One of those who shouted may have been Michael. He drowned there on 2 March 1941, after only three months at sea.

“We don't know why Michael took a job on the Norwegian ship. It may have been a desire to contribute to the war effort, a desire for adventure or a need to make money. He had gone to maritime school, so he obviously wanted to become a sailor,” says Bjørn Tore Rosendahl.

Rosendahl is a historian who works at the Norwegian Centre for the History of Seafarers at War at the ARKIVET Peace and Human Rights Centre in Kristiansand.

A total of 352 British seafarers were killed on Norwegian ships in the Second World War. At least 66 were under the age of 18.

Great power at sea

Norway had long been a major power at sea when the war broke out. Shipping has always been international, and Norwegian ships had crews from all over the world.

One thousand Norwegian ships were sailing the seas when the Germans occupied Norway. They were ordered by radio to return home, but the captains refused and instead went to Allied ports.

At this time, 27,000 seamen worked on these ships. Of those, 3,236 were non-Norwegian.

When the Norwegian government fled the country in April 1940 to escape German forces, they decided that the government now controlled the Norwegian merchant fleet. They created the state shipping company Nortraship to manage these ships and their crews.

Throughout the war, Norwegian ships transported supplies, oil, weapons and ammunition for the Allied countries.

Needed people

But the ships needed people. It was not possible to recruit crews from occupied Norway, so Nortraship hired seamen from other countries.

More than 30,000 seafarers from more than 100 nationalities sailed under the Norwegian flag during the war. This information has only just come to light through the work of the Krigsseilerregisteret, a naval register and digital monument documenting wartime seafarers.

These wartime sailors included 1,000 Danes, 1,400 Swedes and 500 Finns. The British comprised the largest group, totalling 14,000. There were also several hundred sailors from occupied countries, such as Czechoslovakia, Poland and Austria, as well as one German, two Japanese and 290 Italians. At least 2,400 Chinese and 1,000 Indians also worked on the Norwegian ships.

“The reason why many of the sailors came from India and China was that they were cheap labour. They were paid much lower wages than Western seamen,” says Rosendahl.

He does not have figures for how many children, as defined by today’s standards, worked on Norwegian ships.

“We have figures for the Norwegians. When the war started, 4,000 of the seamen were under the age of 18,” he said.

Trapped by the situation

The Norwegian sailors had no choice. They were obliged to work and had to continue to work. This was not the case for the foreign sailors.

“They were more caught up by the situation. They had to earn money, and many could not go home. Besides, they were sailors – that's what they knew how to do,” says Rosendahl.

Nor could the sailors go ashore and wait for the war to end.

“It was not so easy to get a residence permit. The United States in particular tightened up to ensure there would be enough manpower for the Allied countries. Besides, not many countries wanted to have foreign seafarers ashore, wandering around,” says Rosendahl.

So these men and boys took jobs on merchant ships. It was dangerous work.

Half of all Norwegian ships that were bombed or torpedoed sank.

Kai Foo

Fong Kai Foo worked as a repairman on DS Norviken.

The Krigsseilerregisteret does not contain any information about his age, home address or when he enlisted, but the date of his death is certain: 9 April 1942.

DS Norviken was on its way to Bombay. As it sailed past Sri Lanka, the ship was attacked by Japanese planes. Several bombs hit the ship. The crew ran for the lifeboats, but Kai Foo was on duty in the machine room. He awaited orders.

Kai Foo's brother also worked on the Norviken and described what happened in the maritime inquiry. When the second bomb hit the ship, the steam line was blown up. After that, he didn't see Kai Foo again. He himself stormed onto the deck and into a lifeboat.

The planes fired machine guns at the sailors rowing towards shore. Some men swam.

Fifty-three of the crew made it ashore to a beach, where they were cared for by local people. The Norwegian captain and three Chinese sailors perished.

The body of Fong Kai Foo was carried ashore on a raft, badly burned by steam.

He was buried on the beach the following morning, with his brother and a mate in attendance.

Most viewed

Not in the crew lists

Kai Foo's name is known, but it has not been an easy job for the Krigsseilerregisteret to find the names of all the Chinese sailors who sailed on Norwegian ships.

“They often had one Chinese name and one Western name,” Rosendahl said.

Their names were also written in different ways. Lun Kung Yuan, a young apprentice, died in a torpedo attack in 1943. In the maritime inquiry, his name was written Kung Juan Lun. In the wage register in London he was listed as Fung Juan Lun.

Some of the Chinese seamen were never recorded by name.

“They were often hired as a group. One of them signed the contract with Nortraship on behalf of everyone, and only the one person's name was registered,” Rosendahl said.

One of the Norwegian ships, DS Hai Tung, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in 1941. The Norwegian authorities did not have the name of a single one of the 40 Chinese sailors who perished.

The maritime inquiry for D/S Norviken, where Kai Foo worked and died, says that only 9 of the 45 Chinese seamen on board could be identified by name. Three were among those who died and the other six were those who testified in association with the maritime inquiry.

This led to a directive that everyone who sailed on board Norwegian ships had to be registered by name.

Same job, lower pay

Asian seamen were paid less than Europeans.

“They sailed for a war in Europe that many of them did not see as their own. It’s natural that they demanded the same war allowance on their wages as the European sailors received,” Rosendahl said.

Chinese sailors in particular protested, both on British and Norwegian ships.

“Chinese and Indian sailors were considered good sailors, but received lower wages. Now they were exposed to great risk. Moreover, the war, at least from the side of the Allies, was about fighting against a view of humanity that sorted people based on skin colour and race. It was awkward to have different salaries and conditions based on the skin colour of those who sailed,” says Rosendahl.

Eventually, the Norwegian authorities and Nortraship came to individual agreements with Chinese seamen, on each individual ship.

“This is how the authorities avoided committing themselves to the same conditions in the future, when the war was over. And they didn't have to pay higher wages to the crews who didn't protest. It was a tactic they were very happy with,” Rosendahl said.

Not all Norwegians believed that this differential treatment was correct.

“There were a number of people in the Norwegian community who were concerned with changing attitudes towards seamen from other countries. The Labour Party leader Haakon Lie, for example, made a brochure that criticized racist attitudes on Norwegian ships,” says Rosendahl.

Muhammad

Muhamed Hanafy worked in the engine room on the M/S Ringstad. In January 1942, the ship set sail from Ireland with clay for porcelain in the cargo. They sailed in a convoy, but after several stormy days, the Ringstad lost contact with the other ships in the entourage.

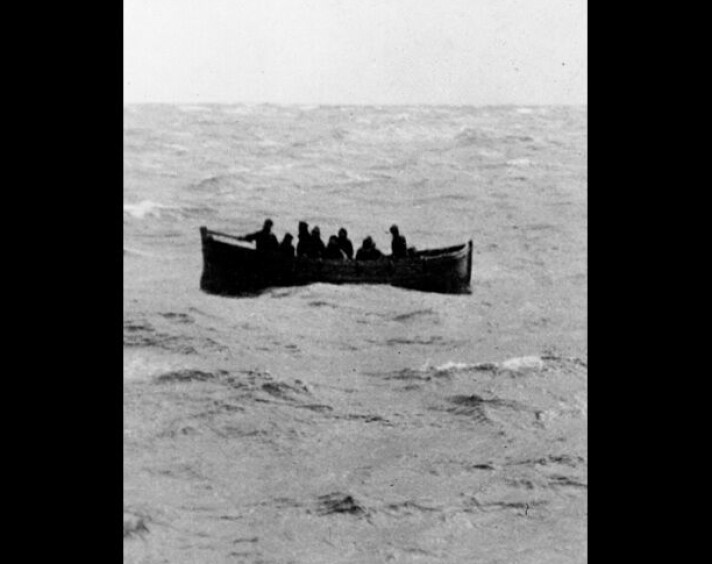

The ship then encountered a German submarine, which scored two full torpedo strikes. The M/S Ringstad sank slowly, and all 40 on board managed to get into lifeboats.

The weather and visibility were poor, and the three lifeboats were unable to stay together.

The 13 sailors in the one lifeboat sat in freezing winds for five days. Water hit the boat and froze into ice. They were then discovered by a plane and taken to Reykjavik.

The other two lifeboats disappeared at sea. On board were 19 Norwegian men, two Canadians, a Dane, a Swede, a Latvian, a Pole, a Briton and an Egyptian, Muhamed Hanafy.

Hanafy was 24 years old when he froze to death in a Norwegian lifeboat. He died in the service of the merchant fleet during the Second World War, and his name is listed in the Seamen's Memorial Hall in Stavern together with all the others who died on Norwegian ships.

No compensation for the families

All told, 953 foreign seamen never returned home.

The families of seamen from Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Iceland were entitled to the same compensation as the Norwegian survivors. Norway and Great Britain also had an agreement on compensation.

“But seafarers from countries without an agreement with Norway, and that was the vast majority, had limited or no rights,” Rosendahl said.

Muhamed Hanafy's family was one of the few exceptions that Rosendahl knows of.

His mother sued Nortraship for compensation because Muhamed's salary supported a large family. They told her that the family had no rights. They still sent £125, thanked their son for his efforts and clarified that it was a one-off payment.

“They obviously felt sorry for her. The families of many of the other victims received nothing at all,” says Rosendahl.

Norma

In 1938, American Norma Hayes went to Scotland to work as a maid on a Norwegian ship. She was 18 years old. While there, she got to know the Norwegian mate Harald Nergaard. Two years later, they married and took jobs on the same ship, the MS Borgestad.

In February 1941, the M/S Borgestad was on its way from Sierra Leone to Great Britain. They first sailed in a convoy with 18 other merchant ships.

“The convoy had no protection, with the exception of a small cannon on the Borgestad,” Rosendahl said.

They encountered a heavily armed German cruiser off the coast of Portugal. It would make quick work of the merchant ships.

“Captain Lars Grotnæss on the Borgestad then chose to sail straight towards the German cruiser, while they shot their small cannon,” Rosendahl said.

The cruiser went to battle with the Borgestad.

“It is obvious that the goal of the Borgestad’s captain was to help the other ships in the convoy. A battle between a merchant ship with a small cannon and a warship could only end with the Norwegian ship being sunk,” Rosendahl said.

The Borgestad sank fast. All on board, 30 men and Norma Hayes Nergaard, perished. She is said to be the first American woman to die in World War II.

With the Borgestad out of the way, the cruiser continued to pepper the other ships with grenades and torpedoes. The German ship managed to sink a few, but the Borgestad delayed the cruiser long enough for 12 merchant ships to escape, saving many lives.

“We don’t know whether the captain alone made the decision to go straight for the German cruiser or whether he consulted with his crew. But I interpret it as a sacrifice they made to save the other ships and the sailors,” Rosendahl said.

Bedrich

Bedrich Scharf was born in Vienna in 1922. When the persecution of the Jews escalated, he fled on foot and alone to Poland and then made his way to Great Britain. There he was taken into a refugee programme and got a job on a farm.

“I didn't like farm work. Besides, I was 17 years old and wanted to impress the ladies,” he said in an interview with the Imperial War Museum after the war.

So when a friend of his told him that the Norwegians needed galley boys, he went to Nortraship in London.

“I had no idea what a galley boy was, but I thought it would be OK,” he said in the interview.

It wasn't just to impress the ladies that he wanted to go to sea. It was 1940, and the war was in full swing across Europe.

“I felt that the war was, in a way, being fought for people like me and that I shouldn't stay out. But I am a pacifist and would not be able to shoot anyone,” Scharf said.

For that reason, he chose service on a Norwegian merchant ship.

Was hijacked

“After a trip on a ship loaded with coal and timber, I chose to hire onto an oil tanker. I thought that if we were torpedoed, death would come quickly. Remember I was a young boy. Even though I had seen people die around me, I didn't think it would happen to me,” he said in the interview.

Bedrich learned quickly and in 1942 got a job as an oiler on M/S Madrono.

He enjoyed himself on board.

“I liked the Norwegians, apart from all their drinking. I hated alcohol myself. But otherwise they were clear-headed and friendly,” he said in the interview.

In August 1942, the German ship Thor lay in the Indian Ocean waiting for ships sailing alone.

The captain of the M/S Madrono did not perceive the danger until it was too late. The Germans gave the order to stop, came on board, took over the ship and took all the sailors prisoner.

The Norwegian officers were transported to the German ship, while a large group of prisoners from other hijackings were put on board the Madrono.

“Many of the prisoners were Chinese, so it made communication difficult, but we made plans to overpower the Germans and take the ship back. Nothing came of the plans while I was on board, but they tried afterwards,” Bedrich said.

He himself went to the German captain and told him that he was Jewish.

Delivered to the Japanese

“I thought it was reasonable. It was better that I said it myself than that they heard it from the Norwegians, who talked a lot. The captain did not react, but told me to go back to work,” he said.

Bedrich heard from one of the German soldiers that there had been a discussion about what to do with him. If they transported him to Germany, he would end up in a concentration camp. But if they handed him over to the Japanese, he would become an ordinary prisoner of war.

So that’s what happened. Bedrich and several others became prisoners in a Japanese camp for the rest of the war.

After the war, he was a translator in the Nuremberg trials, where the German officers were put on trial. He then settled in England with his German wife and two children and worked as a translator in industry.

Frictions on board

It wasn't just wages and risk bonuses that created friction on board.

Most of the Swedish sailors sailed on Swedish ships, because the work was better paid. But 1,400 Swedish sailors worked on Norwegian ships during the war.

“There was a lot of friction with the Swedes on board, they were often unpopular,” Rosendahl said.

When Denmark was occupied, the government collaborated with the Germans. Thus they had no government-in-exile to handle the many Danish ships that were out on the ocean when the Germans took control.

“The Danish ships were taken over by the British, as a kind of spoils of war, and they had to sail under the British flag for most of the war,” Rosendahl said.

Danish seamen consequently were paid British wages, which were much worse than Norwegian wages.

“Danish sailors were called friendly enemies, and the British looked at them with both suspicion and contempt,” Rosendahl said.

“The Danes said that Norwegians sailed first class,” he said.

Didn't like fish cakes

Bedrich Scharf said that he liked Norwegian food, but British sailors complained.

“The British thought there was a lot of fish on Norwegian ships, and fish cakes in particular were unpopular,” Rosendahl said.

Chinese sailors received a small supplement to their wages for cooking their own food.

“Then the Norwegian steward was free to cook food that the Chinese liked,” Rosendahl said.

There has been an extensive effort to register every individual who served on Norwegian ships during the war.

So far, 30,000 foreign seamen have been entered in the Krigsseilerregisteret. This is as many as the Norwegians listed in Nortraship records.

Now both staff and volunteers at the centre are working to investigate all individuals whose nationality is not known.

An important motivation for documenting the efforts and stories of the foreign seafarers has been to show that they deserve the same human dignity as the Norwegians, Rosendahl said.

New knowledge

“In my view, this has been a white spot in Norwegian war history. It’s also about seeing Norwegian war history from perspectives other than Norwegian,” he says.

Guri Hjeltnes, director of the Norwegian Center for Holocaust and Minority Studies, has studied the wartime merchant sailors and wrote a history of sailors of war in several volumes in the work Handelsflåten i krig (The merchant fleet during the war). She welcomes this new information about foreign seamen on Norwegian ships.

She believes the explanation for why Norwegians know so little about these wartime sailors is complicated.

“Firstly, there have always been foreign seamen on Norwegian merchant ships — that’s taken for granted. Secondly, there’s been more of a focus on the history of Norwegian sailors, and that has probably gotten in the way,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

Wartime merchant sailors served on ships that were torpedoed and sunk. They lived in constant danger and knew little about what was happening to their families back home. Nevertheless, it took many years before the Norwegian authorities recognized the seafarers' war efforts.

“In this situation, it is not unnatural that there has been the most focus on the Norwegians,” says Hjeltnes.

Not much research

Another factor is simply that very little research has been done on the foreigners on Norwegian merchant ships during the war.

“That’s why the work of Bjørn Tore Rosendahl is so valuable. We know little about Indian and Chinese sailors in particular,” Hjeltnes said.

When she wrote about the wartime merchant sailors, she went through the crew lists in Nortraship's archives.

“I thought it was very sad, when I wrote about the ships that had been sunk, that the names of Chinese sailors were not recorded,” she said.

“The work of the Archives is incredibly good. It’s now possible to do more research to let us know more about these merchant sailors, how many there were, and not least who they were,” Hjeltnes.

The work is also important for the families and descendants of the seafarers.

“They really appreciate that these stories have been documented, made visible and recognized,” Rosendahl said.

The archive does not have the resources to contact the relatives of the foreign seafarers, however.

“We would like to get in touch with even more descendants, but we don’t know how we will manage that. But by publishing the names and the information we have about them, we are trying to reach out,” he said.

“We see from the Krigseilerregisteret visitor statistics that there are users all over the world, including many from China,” Rosendahl said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Krigseilerregisteret (War sailor register), Norwegian Centre for the History of Seafarers at War, Kristiansand

Bjørn Tore Rosendahl: Seafarers or war sailors? The ambiguities of ensuring seafarers' services in times of war in the case of the Norwegian merchant fleet during the Second World War. Doctoral thesis, University of Agder, 2017.

Guri Hjeltnes: Sjømann. Lang vakt, bind 3 i Handelsflåten i krig 1939-1945.(Sailors. The Long watch, volume 3 in the Merchant Navy at War 1939-1945.) Grøndahl Dreyer publishing house, 1995.

Interview with Bedrich Scharf, Imperial War Museum, 1997.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no