Harassment and threats against Norwegian politicians have increased significantly in recent years

"There is a risk that only the toughest individuals will be able to survive as politicians", says researcher.

Norwegian politicians and people close to them are being subjected to more troublesome comments and threats now than a few years ago.

“There’s been a significant negative development when we combine the serious incidents,” said Tore Bjørgo, a professor of police science at the Norwegian Police University College (PHS).

In 2021, 46 per cent of politicians experienced harassment in the form of physical attacks, threats of harm, property damage or direct or indirect threats on social media.

This represents an increase from 36 per cent in 2013 and 40 per cent in 2017.

“This trend is quite concerning and could impact our democracy. It’s important for politicians to be able to speak without fear,” Bjørgo said.

Significant increase

The researchers conducted identical surveys in 2013 and 2017.

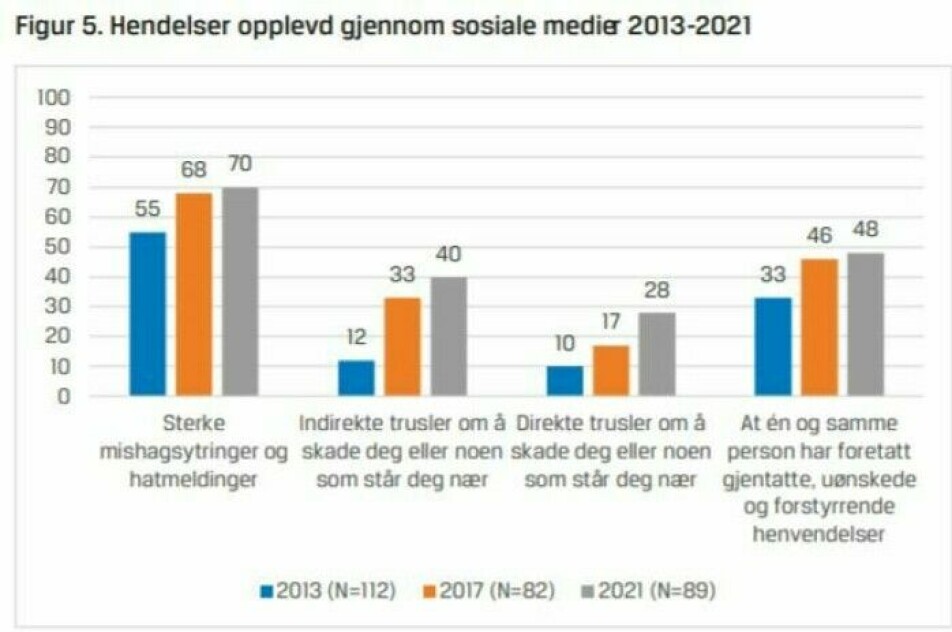

In 2013, 10 per cent of politicians had received direct threats online, which increased to 28 per cent in 2021.

Facebook and Twitter are leading the way.

The number of politicians now considering quitting because of the threats has doubled during the same period.

Four in ten politicians seriously threatened

Members of parliament and ministers have been harassed the most.

87 per cent of the top politicians who responded have experienced one or more adverse events.

Last year, 40 per cent of the politicians and ministers surveyed stated that they had received threats of harm to themselves or their loved ones.

Four years earlier similar surveys showed the proportion to be 29 per cent, and in 2013 ‘only’ 24 per cent.

Three in ten politicians were concerned for the safety of people close to them.

Admittedly, the percentage of respondents was only 53 per cent.

“It’s conceivable that those who responded were more exposed to negative contacts than the others,” Bjørgo says.

Some comments may be punishable

The most prevalent comments take the form of bothersome and unwanted messages on social media, typically strong expressions of displeasure and hate messages. Seven in ten politicians have experienced this type of online harassment.

Up to four in ten have received direct or indirect threats stating that the sender would harm the politician or close family.

“It's easier to say ugly things to someone you aren’t talking to in person,” said Bjørgo.

Before the onset of online media, people used to submit letters to newspapers, where their comments would be edited before publishing.

"A lot of people don’t understand how violent the impact of harassment can be, and they don’t know that some of it is punishable," Bjørgo said.

But very few incidents result in prosecution.

The Norwegian Police Security Service (PST) is responsible for protecting the most important politicians, and advises police districts if politicians receive threats that may be punishable.

“The vast majority of statements are legal, but they can be unpleasant. The PST wants to contribute to making politics safe,” said Hans Sverre Sjøvold, the head of the PST.

Is the pandemic a contributing factor?

The pandemic has resulted in more people sitting at home and spending more time on social media.

“The pandemic situation may explain some of the recent increase in online harassment,” said the PST chief.

Social media brings many different extremist groups together, which use very harsh vocabulary. Bjørgo believes that greater societal polarization could also be a factor.

“Maybe trust in the authorities has diminished during the pandemic. We can see this when it comes to anti-vaxxers, who promote the idea of a conspiracy theory,” he said.

He believes this type of attitude involves a lack of trust in other people and politicians.

Compared to other countries, Norway generally has a high degree of trust in society and hasn’t dealt with such an extreme lack of trust, Bjørgo said.

Norwegian Progress Party and young politicians most vulnerable

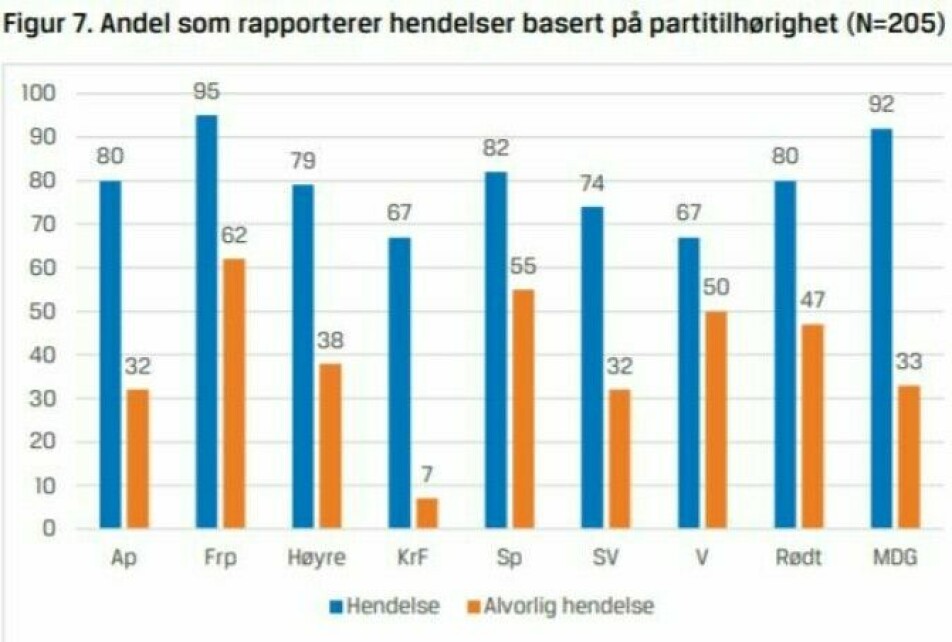

Politicians from the populist Norwegian Progress Party (Frp) experience the greatest number of serious incidents, at 62 per cent. Green Party (MDG) politicians experience almost as many unwanted contacts as Frp members, but fewer of them are serious.

“Harassment and chicanery are unfortunately something you have to endure and learn to live with if you want to stay in this job. If not, you’ll have problems coping with everyday life,” Sylvi Listhaug said to the Norwegian national broadcasting corporation, NRK.

While she was Minister of Justice, Listhaug received death threats, which meant that she needed to have bodyguard protection.

“We don’t know the reason, but it might be because the Frp has controversial opinions and restrictive views on immigration that offend a lot of people,” Bjørgo says.

There is a clear connection between being in the media often and being vulnerable to unwanted contacts.

Young politicians of both sexes between the ages of 26 and 35 are at greatest risk. Seven in ten youth politicians had experienced adverse events. Young female politicians are not significantly more vulnerable than their male counterparts.

Female politicians are sexually harassed

“But female politicians are much more vulnerable to sexual threats and react more strongly than men as regards their fear level,” Bjørgo said.

However, most women stated that they did not get scared at all or only minimally.

Bjørgo worries that harassment by people with opposing opinions may push young people away from politics.

Many young politicians report that they have become concerned about being out in public, with 19 per cent saying they avoid or hesitate to speak out on controversial political issues.

About 15 per cent state that they are considering quitting politics.

“We think this is serious because there is a risk that only the toughest individuals will be able to survive as politicians. We could miss out on a lot of people who have important life experiences to contribute,” Bjørgo says.

Angry and malicious comments exact a significant cost, which could affect the recruitment to elected positions, he said.

"Unfortunately, we most likely won't notice the voices that are silenced", Bjørgo says.

Assumed motives

What is the motive for inciting hatred against politicians?

“Interest in a particular political topic or issue where there is strong disagreement with certain politicians is obvious,” Bjørgo said.

But many also show signs of believing in conspiracy theories.

Many individuals who harass others are in conflict with public authorities, such as child welfare services or NAV, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration.

Reference:

T. Bjørgo, G. Thomassen and J. Strype: Trakassering og trusler mot politikere: En spørreundersøkelser blant medlemmer av Stortinget, regjeringen og sentralstyrene i partiene og ungdomspartiene. (Harassment and threats against politicians: A survey among members of the Storting, the government and the central boards of the parties and youth parties). Norwegian Police University College, 3 February 2022.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no