Still publishing research articles at nearly 102 years old

The first time she participated in fieldwork was in the 1940s, the last time was in 2020. And soon, another research article will be published with geologist Kari Egede Henningsmoen listed as one of the authors.

In 1960, the Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad arrived at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland. There, he found some house foundations that resembled the Norse settlements he had excavated in Greenland. Both radiological studies that dated the foundations to around the year 1000 and artefact discoveries confirmed that it was a Norse settlement. Helge Ingstad had found the Viking’s Vinland.

In the spring of 1962, palynologist Kari Egede Henningsmoen travelled to L'Anse aux Meadows to work with the couple Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad in Newfoundland. Using pollen analyses, Henningsmoen wanted to uncover the area's vegetation history and changes in sea level.

Too cold for grapes

“My task was primarily to find out what the climate was like in the area around the year 1000,” says Henningsmoen.

She determined that it was not warm enough for grapes at that time, which supported the theory that Vinland means flat land and has nothing to do with wine at all.

During her first field season, she lived in a tent. She and a young man who also participated in the expedition each had their own tent. Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad shared a tent.

“One night there was a phenomenal storm, and we all sought refuge in the large kitchen tent. The floor was sealed, but the roof was not, and you can imagine what happened,” she says.

The water level rose until all four of them ended up with their legs in the water. The next day, the two women were allowed to move into the house of a nearby farmer.

In 1968, Henningsmoen returned to do further research. She describes the collaboration with the Ingstad couple as good and the work as fun, but when she looks back, she says none of the countless projects she has worked on over the years were research highlights.

“Everything I've researched has been exciting,” she says.

An offer she couldn't refuse

Most viewed

Kari Egede Henningsmoen grew up in Oslo, with a father who was an electrical engineer and a mother who stayed at home, as most mothers did at the time. But her mother had some unusual hobbies. Among the subjects that interested her were Slavic languages and hieroglyphs. Her mother also played the piano.

“I also tried my hand at the piano, but I lacked the talent,” she admits.

But as a child, she also had another hobby: collecting plants for a herbarium. The first course Henningsmoen took when she started her studiies in the autumn of 1943 was therefore a botany course. But it was short-lived. The University of Oslo closed that same autumn, and Henningsmoen had to postpone her studies until after the liberation of Norway at the end of World War II.

After completing her foundation courses in botany and chemistry in 1947, she was asked if she would like to write her master's thesis under the supervision of Professor Knut Fægri in Bergen. He was one of the first in Norway to use pollen analysis.

“It was an offer I couldn’t refuse,” she says.

In Bergen, she also learned to analyse diatoms. These are a type of algae primarily found in seawater. Henningsmoen used this method in her research on land uplift.

“I have always been treated well"

In her master's thesis, which was published in 1950, Henningsmoen describes the vegetation history of two bogs in Østfold county, Eastern Norway.

With a grant from the Research Council of Norway, she then began taking samples in bogs and small lakes in Vestfold.

When the grant expired, she was hired as a research assistant at the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), and in 1958, she became NGU's first female state geologist.

Being a woman in a time when academia was dominated by men has never been a problem, she says.

“I have always been treated well, and I was lucky to quickly build a good network,” she says.

In 1962, she married geologist Gunnar Henningsmoen.

When NGU relocated to Trondheim that same year, Henningsmoen chose to stay in Oslo.

She first got a temporary position, and later a permanent job at the University of Oslo's Department of Pharmacy, where she taught students in botany.

But it was not until she got a permanent position at the Department of Geology in the late 1960s that she had the opportunity to teach what was closest to her heart: analysis of pollen and diatoms.

A warm and caring person

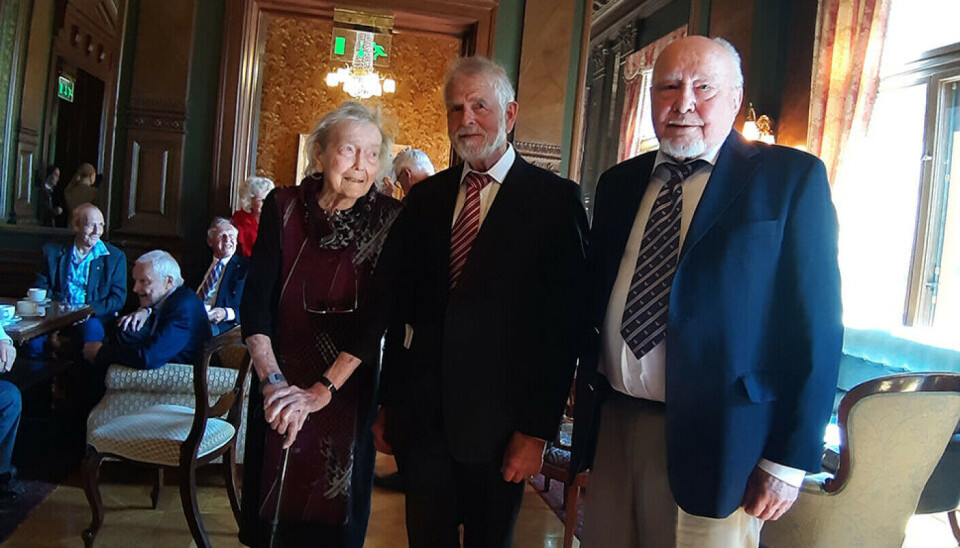

We meet Kari Henningsmoen at the premises of the Department of Geology together with palynologist Helge Høeg. Henningsmoen still regularly visits the department, and when she does, it's usually with Høeg as a collaborator. They have known each other ever since he became her first graduate student in the late 1960s.

Henningsmoen continued supervising graduate students until she was 84 years old. In the commemorative publication released for her 100th birthday, she receives high praise from several former students, says Høeg.

“She's described as very thorough in her work, but also as a warm and caring person. At the department, she was a real asset. There was always an open door at Kari's home,” he says.

When Henningsmoen returned to Vestfold in the 1960s and 70s to take new samples with increasingly better equipment, Helge Høeg often joined as her field assistant. Other times, her brother Hans Olav Egede Larssen or her husband Gunnar Henningsmoen accompanied her into the field.

Høeg himself has continued conducting pollen analyses and later also charcoal analyses, both as a temporary employee on countless projects and as a contractor through his own company. Høeg is also known as the man who started pollen forecasts for allergy sufferers in Norway, as well as his analyses of honey.

An interdisciplinary researcher

In the celebratory publication for Henningsmoen's hundredth birthday, she is described as an interdisciplinary researcher who moved effortlessly between the fields of botany, palynology, geology, and archaeology.

When archaeologist Charlotte Blindheim conducted archaeological excavations at Kaupang in Vestfold from 1954 to 1974, Henningsmoen was called in. She was also called upon when Dagfinn Skre began new excavations at Kaupang in 2000.

The excavations led by Skre were also the start of what Helge Høeg jokingly refers to as the retiree triumvirate, a collaboration between Kari Henningsmoen, himself, and geologist Rolf Sørensen.

The three also worked together on the excavations along the E18 highway, the Brunlanes project, which began in 2007, and on the Vestfold railway project launched in 2010. Together, the trio have also continued Henningsmoen's studies in Vestfold and Telemark.

The last time they were out in the field together was in 2020. Henningsmoen was 97 years old, Høeg 73, and Sørensen 81.

This year, a new article will likely be published with the entire triumvirate, along with biologist and water chemist Veronika Gälmann, listed as authors.

The expected title is: Holocene vegetation history and land uplift in southern Vestfold and southeastern Telemark. In: The Stone Age in Telemark. Archaeological Results and Scientific Analysis from the Vestfoldsbaneprosjektet and E18 Rugtvedt-Dørdal.

No secret formula

Kari Henningsmoen turns 102 on May 30. She's not quite as quick on her feet as she once was, but she still climbs the 39 steps to her apartment, and she remains a sharp discussion partner on academic topics, Helge Høeg says.

“Kari has the memory of an elephant,” he says.

“How have you managed to stay active and sharp for so long?” we ask her.

It's a question Kari Henningsmoen has been asked before.

“I don't have a secret formula. I haven't lived a particularly healthily – I've just lived a completely ordinary life,” she says.

This article was first published on Uniforum. Read the original article here.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.