Twin study: Genes explain only a third of our psychological resilience

A new, Norwegian twin study reveals that people who think life is meaningful, are physically active and have good relationships with their loved ones, are far better equipped to cope with stress.

Most people get their nose bent out of shape or encounter obstacles one or more times in their lives. Some people become anxious, depressed or dissatisfied, while others think life is good despite the challenges they’ve faced.

The latter group is more psychologically resilient or robust.

But what affects how well equipped we are to cope with stress? Are we born like that or do we develop the skill?

According to a new study, surprisingly little can be blamed on genes when it comes to resilience.

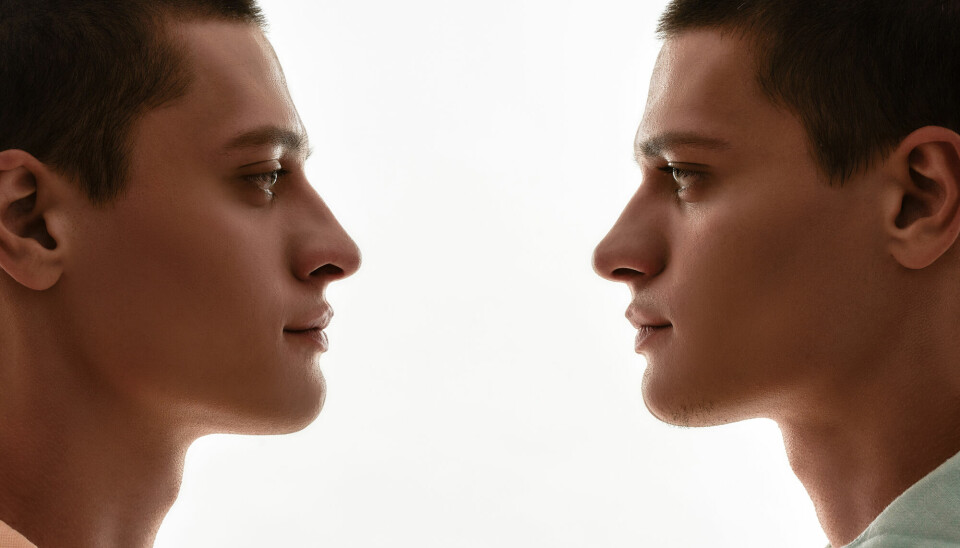

Twins with completely and partially identical genes

To find out whether genetics or the environment affect our psychological resilience more, psychologists at the University of Oslo (UiO) conducted a large study with almost 2000 Norwegian twins.

Both identical and fraternal twins were part of the study. Monozygotic twins are genetically identical, while dizygotic twins share about half of their genetic material just like any other siblings.

“Based on this information, we can calculate how much of the differences between the participants is due to heredity and how much is due to the environment,” says Live Skow Hofgaard. She is a psychologist and a PhD candidate at UiO’s Department of Psychology.

All the twins grew up together, so similarities within the twin pairs could be due to shared family environment and shared genetics.

Greater similarity between identical than fraternal twins indicates heredity. Differences within twin pairs are due to their different experiences.

Best equipped to cope with traumatic experiences

The twin pairs ticked off how many stressful or traumatic events they had experienced in a questionnaire. The twins were on average 63 years old, so most had experienced some adversity during their lives.

In addition, they stated whether they had symptoms of anxiety or depression and how satisfied they were with life.

“We observed that you can be satisfied with life even if you experience symptoms of anxiety and depression, so therefore we included two different measures for mental health,” Hofgaard explains.

Each participant received a score based on how well they coped mentally, relative to how many difficult experiences they had been through.

Those who did better than expected – compared with others who had experienced the same number of difficulties – were considered robust.

Then the researchers calculated the role that heredity played.

Identical twins twice as similar

How psychologically robust the participants were varied between both monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs.

As expected, the researchers found that identical twins were more similar to each other in their psychological resilience – by about twice as much –than the fraternal twin pairs.

Heredity clearly played an important role, but how important exactly?

“We calculated that about 30 per cent of the differences between the participants in how well they managed, despite difficult experiences, was due to their different genes,” says Hofgaard.

The rest of the variation could be explained by differences between the co-twins, that is, the differing environmental influences each one experienced, says the researcher.

One twin could be more satisfied with life than the other twin despite having experienced several horrific events.

Different resources in the environment

Various environmental factors then, account for as much as 70 per cent of the explanation for differing psychological resilience.

Hofgaard explains that the role environment plays in how well we emerge from difficult experiences involves external and internal resources.

“These resources include those we have in the environment around us when we need them and how accessible they are, and our inner resources that have developed partly based on our life experiences,” she says.

Different life experiences

Twins grow up in more or less the same environment. But as they grow, they go through different life experiences. Some lose their jobs or get divorced. Others become seriously ill.

“Different lives may also contribute to twins developing different characteristics. One twin might be more optimistic than the other based on their experiences,” says Hofgaard.

To find out what may contribute to psychological resilience, the researchers studied differences between identical twins.

“This is like imagining that the same genetic starting point has lived two different lives, and then finding out how the differences impacted psychological resilience,” she says.

“We looked more closely at whether twins who were more robust than their co-twins also had other characteristics that distinguished them from their twin.”

They investigated differences in physical health, social life, socioeconomic status and psychological characteristics.

Three protective factors

In the participants who were more psychologically robust than their respective twins, the researchers found three clear distinguishing characteristics:

- They lived in good relationships. This was especially important for maintaining life satisfaction despite adversity.

- They were more physically active. This especially prevented symptoms of anxiety and depression despite difficulties.

- And they experienced that what they did in life was meaningful. They filled their lives with meaningful activities, or found meaning in the activities they spent time on. This strengthened both forms of resilience.

Given that these factors are also different for identical twins, the relationship is independent of genetics, and thus malleable.

“Changing our life situation with a focus on these factors can make us stronger in the face of adversity,” says Hofgaard.

Genes do not only have direct impact

A previous study on twins has pointed out that genetics could affect children through the environment their parents create.

So, depending on whether you measure only the direct effect of the parents' genes or also include the environmental effect of their genes, the risk of depression among children increases from 19 percent to 37 percent.

- Read more about that study in this article: Nature or nurture? Here’s what researchers found out when they studied children with depression

More research needed

Hofgaard notes that there is still a lot to learn about the causal relationship or the time sequence between lived experiences and protective environmental factors.

“We don’t know enough about this yet. For example, we can’t be completely sure whether perceived meaning in life makes us more resilient, or if coping well despite adversity leads to a stronger experience of meaning – or a combination,” she says.

She believes further studies on the topic are needed.

“We’d like to carry out studies that go on for a longer period of time, so that we can be more sure of the causal connection,” says Hofgaard.

Reference:

L. S. Hofgaard et al: Introducing two types of psychological resilience with partly unique genetic and environmental sources.. Scientific Reports, 2021.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no