Plastic waste from Norwegian hospitals could fill 100 football pitches every year, according to report

A good part of this plastic waste could be avoided, the report shows.

Large quantities of disposable gloves and medical products, packaging and plastic textiles end up in the trash in Norwegian hospitals.

Annually, they may amount to as much as 20 000 tonnes of plastic.

This waste is equivalent to 100 football pitches covered by a one metre layer of plastic, or 40 per cent of all the plastic thrown away in Norwegian households.

The waste consultancy company Mepex collaborated with Oslo University Hospital (OUS) to calculate their new report.

The survey shows that good opportunities exist to cut down on some of the plastic use. The survey was financed by the private fund Norwegian Retailers' Environment Fund.

Looked through 200 kilos of waste

Hildegunn Bull Iversen and Elise Narum Amland, both senior advisers at Mepex, suited up in infection control equipment and analysed the waste from three departments at Oslo University Hospital.

During 36 hours, Iversen and Amland looked through 200 kilograms of residual waste.

The waste came from the operating department, the intensive care unit and the emergency department at OUS.

“We found a lot of different items that ended up in the residual waste and that strictly speaking did not need to be there. Not surprisingly, we found that a lot of it was plastic,” says Iversen.

“Around 60 per cent of the waste we went through was plastic. We’ve analysed this down to polymer type and type of product.”

Disposable gloves and trash bags

The one product they found the most of were disposable gloves. The gloves alone accounted for 18 per cent of the plastic waste.

Next came trash bags at 17 per cent. The trash bags themselves make up a large part of the waste, because many of them are disposed of when they are only partially filled.

Disposable textiles made of plastic accounted for 13 per cent of the waste, while packaging accounted for 21 per cent.

Scaled up survey

Iversen and Amland used their analysis along with waste statistics and purchasing figures from OUS to calculate how much plastic is thrown away at Norwegian hospitals nationwide. They did this by scaling up their survey based on patient numbers.

The researchers concluded that Norwegian hospitals burn about 20 000 tonnes of plastic a year. They included estimates of the plastic content in infectious waste, which they did not have access to.

The calculation indicates that 400 tonnes of unused products are thrown away each year.

“When products are unpacked in proximity to patients, they cannot be returned to the storeroom. This means that you throw away a lot of products that haven’t even been used,” says Iversen.

The total tally of disposable gloves, supported by OUS purchase figures, came to 1300 tonnes a year.

Uncertain numbers

Senior researcher Cecilia Askham works at NORSUS Norwegian Institute for Sustainability Research.

Regarding the method used to scale up the numbers, she writes to sciencenorway.no that these figures can only be used as a cautious estimate of the quantity and composition of the waste.

We shouldn’t think of these figures as definitive, she says.

“The variations between patients, departments, between days of the week or seasons of the year, and between patient groups treated in different departments can be great and thus create large discrepancies in the figures,” says Askham.

However, she believes it is extremely important to consider this topic and take action on the hospitals' use of plastic.

Solutions can be found

In addition to the waste analysis, Iversen and Amland participated in inspections at the hospital where they followed the products' journey from purchase to waste. They also spoke to people from various parts of the value chain.

Is it possible to reduce the use of plastic?

“We absolutely believe it’s possible,” Iversen says. “The mapping of the waste's journey through the hospital demonstrates the need for increased awareness around the purchase, use and handling of plastic along the entire value chain – from when the need for a product arises and is described until it has to be handled as waste. The environmental cost of plastic needs to be factored into the balance.”

Interviews and a workshop with health personnel provided input on what is possible and justifiable to take action on. The researchers also looked at experiences from other countries.

“We see that for some of the disposable products that generate a lot of waste, other solutions are available that could also provide cost savings for the hospitals.”

“For example, it would be possible to replace disposable plastic textiles with similar products that can be washed and reused,” says Iversen.

Can save tonnes of plastic

The measures consist of eliminating, switching and sorting products to make such replacements.

Raising awareness of all the unused products that are thrown out and reviewing the routines could save 200 tonnes of plastic from ending up in hospitals’ residual waste annually, according to the report.

Another area where hospitals can save on plastic use is with pre-packaged procedure kits. They are designed to enable the necessary tools to be accessed quickly.

Some of the sets in current use contain products that are not used and are thus thrown away unused. Weeding out the unnecessary products could save 20 tonnes of plastic.

“We’ve looked at sheet protectors, which are absorbent pads that you use to soak up moisture. They’re used in various contexts. We found out in our conversations with healthcare personnel that they don’t always need to use such large sizes. Adapting the sizes better could reduce how much material is used per product.”

This measure has the potential to save 130 tonnes of plastic.

Make demands of suppliers

Syringes are one of the products that are thrown away a lot.

“We looked at a Swedish attempt to reduce plastic waste where the syringe thickness had been reduced. By making them thinner, you can produce it with less material,” Iversen says.

This measure would save 80 tonnes of plastic a year, according to the report.

“Then there are a number of products that are double-packaged. I know that hospital purchasing is already making demands in its tenders to address this.”

Cardboard cups with plastic film or plastic glasses are often used even when there is access to a dishwasher nearby. Cutting out their use would save 120 tonnes of plastic.

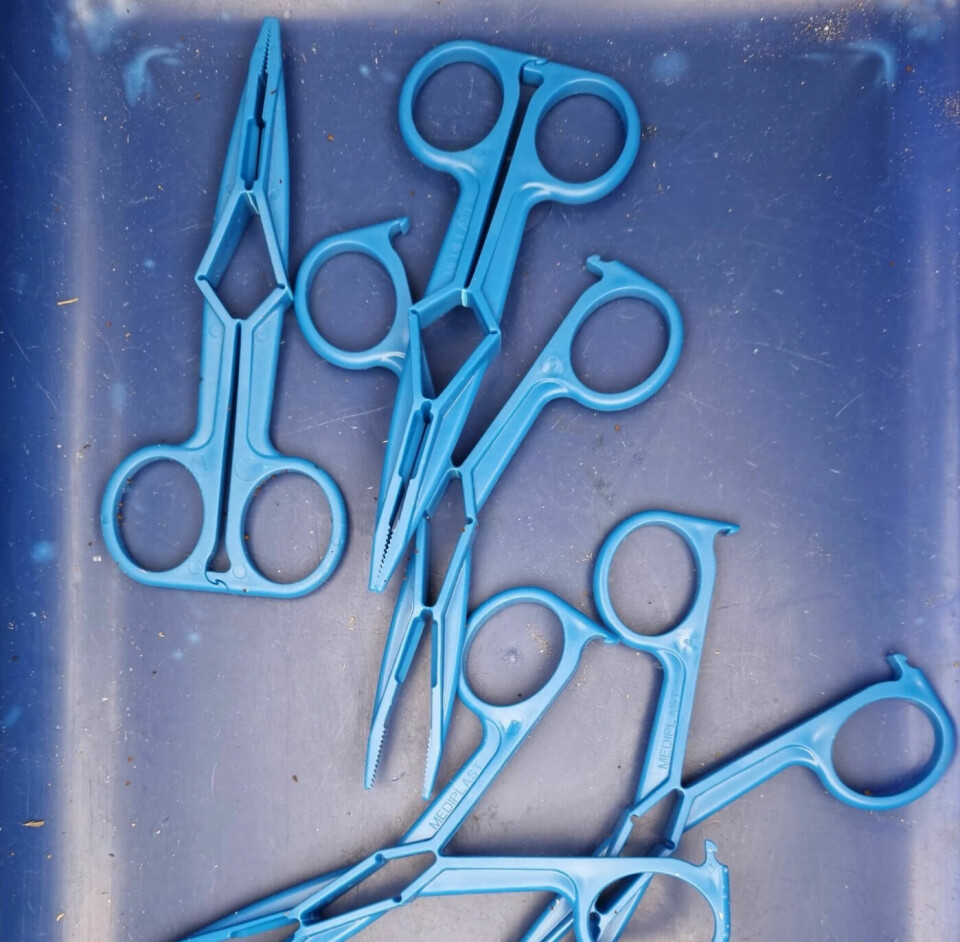

Certain disposable products like scissors, tweezers and respirator parts can be replaced with reusable products.

The waste analysis indicates that almost 3000 tonnes of bags are thrown away annually. Many of the smaller bags are only partially full when they are discarded. Changing the cleaning routines could help save 280 tonnes of plastic.

Employees react to consumption

Iversen also believes that more sorting of plastics at their source in hospitals can be done, but a good sorting infrastructure and agreements for post-sorting and recycling of the sorted plastics need to be put into place first.

“We noticed that the plastic is very clean, and a lot of it would be suitable for material recycling. Other items, like diapers and hoses, can cause problems with further handling. We simply have to test out more options.”

Iversen adds that employees are motivated to do something about the problem.

“A lot of people are reacting to the high consumption and want to change that and eliminate more plastic products.”

Iversen hopes that the report can inspire more hospitals to take action on their plastic use.

“Plastic is a high-quality material with a long shelf life, and it’s a shame to burn so much of it every year. In the long term plastic could become a scarce resource that we have to reserve for things that will last a long time.”

Important first step

Askham says that mapping and assessing action measures is very important as a first step in being able to work towards reduced use.

She points out that the measures in the report are divided into eliminating, switching and sorting products.

“I think that’s a good presentation that aligns with circular economy thinking,” Askham says.

“Reducing consumption should be the first priority, then making products more circular and putting materials into greater circulation.”

Askham thinks interviewing people who actually work at the hospital is also a good thing.

“Talking with employees provides more practical measures that can more likely be carried out.”

There are good proposals for ways to address products that are important in the analysed waste, says Askham. These are products that you see across departments in hospitals.

“The proposed measures and the estimated saving percentages could well be accurate for these products.”

Askham points out that increasing the amount of data from more departments and hospitals could give the numbers greater validity.

“But the report suggests several measures that would enable hospitals to act now and achieve savings.”

Overuse, especially of gloves

Mette Fagernes is a senior adviser at the at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health’s (FHI) department for antibiotic resistance and infection prevention.

She has taken a quick look at the report.

“This is a topic that is important and relevant. The report points to several important measures to reduce the environmental impact of health service activity,” she says.

Fagernes’ work includes hand hygiene and protective equipment. She says that the environmental impact of using protective equipment is an issue of concern for FHI.

“The health service is concerned with ensuring employees’ safety against infection and minimizing the risk of cross-infection between patients.”

“That perspective can foster the use of protective equipment ‘for safety's sake’, without adequately considering the environmental consequences. We’ve seen a growing overuse of protective equipment, and gloves in particular, within the health service,” Fagernes says.

Planning review of guidelines

It is important to ensure that the use of protective equipment balances consideration of the risk of infection and the environment, says Fagernes.

“The Institute of Public Health provides national guidelines for the use of personal protective equipment in the health services and tries to contribute to its correct use through clear advice, teaching materials and campaigns.”

As a consequence of the high consumption of protective equipment and the environmental impact this precipitates, FHI is planning a new review of the national guidelines in autumn 2023, says Fagernes.

Reference:

Mepex: Prosjekt Plastsmart sykehus (Plastic-smart hospital project), August 2023. (Link coming)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

-----