Discovered unknown species deep underground

In pitch darkness, a kilometre below the surface, a ghostly insect hovers between cave walls. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says researcher.

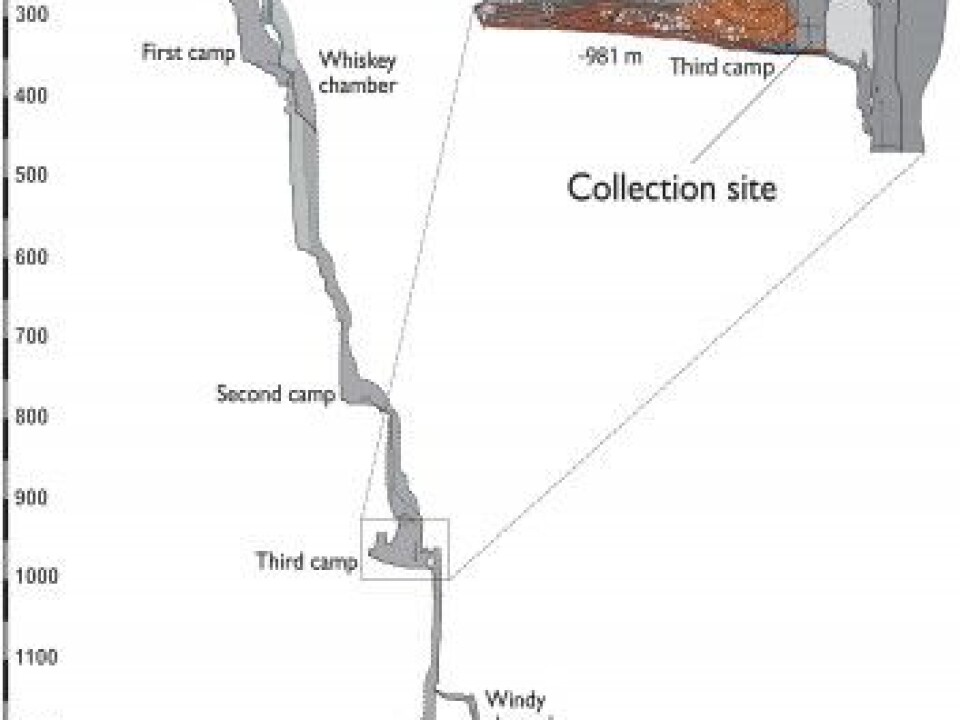

The Lukina Jama-Trojama Caves in the Dinaric Alps of Croatia are no place for cowards.

A nearly vertical abyss plunging more than 1,400 metres calls for extreme climbing and spelunking skills – and the coolest of nerves. A slim waistline helps too, as the narrowest parts of the shaft are just 40 cm in diameter.

For the few who have what it takes, this journey toward the centre of the Earth can be worth the effort.

These caves are among the richest in the world with regard to completely adapted cave creatures. It is the only place on the planet where scientists find molluscs, sponges, jellyfish and bristle worms that live their entire lives under ground.

The latest amongst these new cave species is a ghostly white midge – a non-biting gnat or mosquito-like insect – that lives 1,000 metres down underground.

Questions immediately arose about what this little bug was. Eventually some specimens were sent to scientists at the University Museum of Bergen.

“I’ve described several species from rain forests round the world but I have never seen anything so specialised,” says Associate Professor Trond Andersen. He and colleagues from Norway, Germany and Croatia have now studied the midge.

It flies!

Following extensive examinations of the DNA and body parts of this strange insect, the researchers concluded that it was a new genus of midge. This genus consists so far of just the one bug, now given the Latin name Troglocladius hajdi.

Andersen says the T. hajdi is truly special.

“Compared to most midges it is very pale.”

But that is just the beginning.

While similar insects usually have well-developed vision, T. hajdi only has strongly reduced eyes. It is completely blind. It also has exceptionally long legs.

Andersen says this is an adaptation to life in a cave.

“A creature will develop what it has a need for, whereas parts that are no longer useful gradually diminish.”

Eyes are of no use in the darkness of a cave. Nor does it need camouflage or protection from sunlight, thus the lack of pigment. But long legs are useful for feeling its way around.

But T. hajdi has one trait that really surprised the researchers. It still has wings. Moreover, they are large, apparently functional wings that should provide plenty of lift.

This cave midge must fly!

Parthenogenetic

“We are pretty sure that it flies,” says Andersen.

“Some of the specimens were caught on a sticky plate and they were stuck halfway up it. We have to assume that they flew there.”

If so, this is the world’s first example of a creature that lives entirely in a cave that can also fly. Bats, for instance, come out into the open.

Andersen thinks the insect hovers slowly on its broad wings while feeling about with its long legs. Maybe it also flies up to good spots to lay its eggs?

This is conjecture.

There are lots of unanswered questions about the bug. One is: Why were there no males among the 16 specimens of T. hajdi caught to date?

Perhaps only females exist and they propagate parthenogenetically? In other words, unfertilised eggs develop directly into new individuals.

Looking for the larvae

“I would guess this to be the case. Parthenogenetic propagation is not uncommon in insects. Especially among species in small and specialised habitats,” says Andersen.

The life of T. hajdi is a mystery for now.

New expeditions deep into the Croatian abyss will attempt to get the answers. In particular, scientists hope to find solid evidence of flight capabilities, where the larvae live and what the larvae eat. Perhaps they feed on a bacterial coating of the cave walls.

One thing Andersen is currently convinced of is that this is the first midge known to live its entire life below ground. And this bug only lives in a tiny part of the Lukina Jama-Trojama Caves.

Perhaps there are only a few hundred individuals in the entire world.

Could be mistaken

Even though Andersen thinks the right spot for the insect on the tree of life has been found, new information could change the current taxonomy.

It was hard to make the DNA analyses from the specimens gathered to date. And no thorough charting of all other midges has been made. So there is a possibility that T. hajdi has closer relatives than believed.

In that case it would not be classed as a genus branch of its own. It would be a new species, adapted to life entirely in a cave, but in the same genus as terrestrial midges. In either case, T. hajdi must have evolved in the course of several hundred thousands of years after ancestors buzzed into these caves.

“We don’t know what future research will bring,” says Andersen, who is now retired after 30 years as a taxonomist.

“This is what makes this job so exciting.”

------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling