Three-step drying keeps people fed in Faroe Islands

“The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind.” Dylan’s refrain is also applicable to the question of how fish, meat and poultry can make it to the plate year round without a freezer or fridge.

Salt was expensive, the climate wet and access to food unbalanced and unassured. How did the Norse and Norse-Gael settlers get their proteins 1,000 years ago, also on days when the fish weren’t biting and the slaughtering season was weeks ahead?

Wind drying

The Faroe Islanders had to rely on nature, including the wind. The result was a natural conservation method that might seem unusual. Not only was meat and fish served dried, but it could also be eaten before the drying process was complete.

Jóan Pauli Joensen celebrated his 70th birthday with the publication of a two-volume book about the food traditions of the Faroes.

“Here we really know whether the fish is fresh or not. If it isn’t fresh it gets dried,” explains Jóan Pauli Joensen.

The former rector of the University of the Faroe Islands celebrated his 70th birthday by publishing his own two-volume coffee table book on his country’s food culture, now and in the past.

“It is all interrelated. Business, food, drinking and customs. The most important issues for people have always involved getting food on their plates and a roof over their heads,” says Joensen.

Little salt, no juniper

“Salt was costly. In the old days there was juniper growing which could be used for smoking food, but it was almost wiped out back in the Middle Ages. So we had to dry all our food to conserve it,” he explains.

Ethnologists and gourmets can appreciate that necessity, even today:

“We are so lucky to have a climate that starts the fermentation process before the meat or fish has fully dried. This is what gives that special umami taste.”

“Nowadays we eat this because we like it, so the drying process is still an important part of our food culture here,” says Joensen.

Unsmoked

He was a professor of ethnology at the University of Bergen, but does not want to compare the Faroe Islanders wind-dried dishes with traditional Norwegian food. One Norwegian relative might be the Christmas dish from the west coast, pinnekjøtt, which are dried ribs of mutton that are soaked and steamed.

“Salt was used, but not in curing, it was just for the taste. Just a couple hundred years ago, the only people who could normally afford smoked food were the clergy and government officials.”

“In our popular food culture, smoked foods have not really existed. Except when sausages were made and hung over fireplaces. But that isn’t smoking in the traditional sense of the word,” says Jóan Pauli Joensen.

More variety

Eldbjørg Fossgard sees more differences than similarities between the traditions in Norway and this group of islands between Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic, which was a dependency of Norway until 1814:

“One of the special traits of Faroe Island food culture is that they have a wider variety of ways to conserve meat and fish than we have in Norway,” says Fossgard.

She is an associate professor at Bergen University College and specialises in food in a cultural and social perspective. She has also reviewed Joensen’s food books.

Shrivelled, stored and dried

“There used to be less access to salt. This is no argument today – now it’s more about getting another taste. When they dry meat without salting it, a fermentation process starts simultaneously,” she explains.

This is where a three-stage drying process comes in. The Faroe Islanders discern between visnað (withered), ræst (semi-dried or stored) and plain old dry.

“First the meat withers, then it starts to ferment and then it dries. These stages give different tastes and consistencies,” says Fossgard.

She admits that she doesn’t really have a taste for this meat, which she compares to lutefish: Some Scandinavians like it, some don’t.

Fermented and boiled

Food is prepared in different ways depending on what stage it is in:

“When dried, you eat it without cooking it. In the intermediate stages – withered and semi-dried – you boil it,” says Jóan Pauli Joensen.

Meat and fish gets the same treatment, except that mutton is not often eaten in the initial, withered stage.

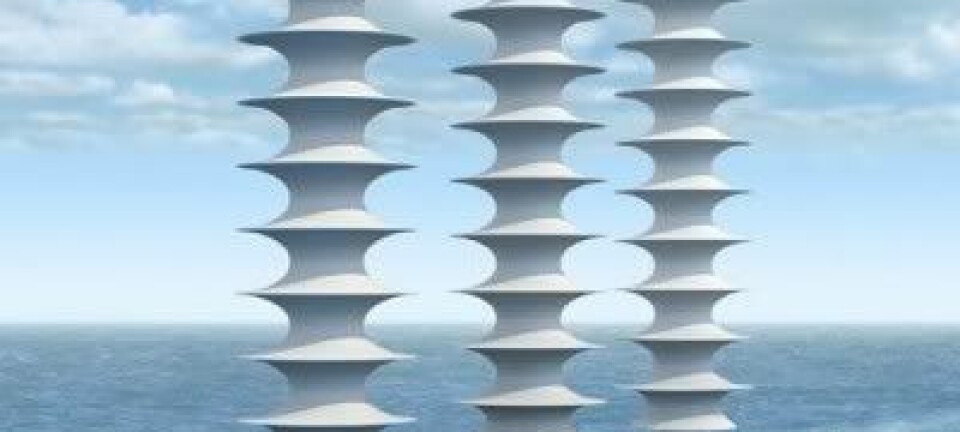

“The processes are the same, but we hang fish and meat separately. The important thing is also to hang it on a string or hook so that air circulates all round. You have a problem when any part is in contact with another surface. The bacteria multiply too much and the process can get hazardous,” says Joensen.

Pilot whales and seabirds

In addition to fish, sheep and a little beef, Faroe Islanders have traditionally eaten seal meat and perhaps most notoriously – pilot whales.

They have had to rely on seabirds for proteins too: Puffins, black guillemots, white-breasted guillemots, auks, gannets and northern fulmars. These are said to taste best fresh, but they too are conserved for dinners in the harsh winter months.

Eldbjørg Fossgard hopes that young Faroe Islanders maintain interest in food conserved in the traditional way. Fermentation can be trendy – like making your own sauerkraut or kimchi with bacteria cultures, and of course, brewing your own beer.

“Young people are just as modern on the Faroe Islands as in Norway. But I think the smaller the nation, the more necessary it is to consciously preserve a culture,” says Fossgard.

References:

Jóan Pauli Joensen: Bót og biti. Matur og matarhald í Føroyum. Faroe University Press – Fróðskapur. 2015.

Jóan Pauli Joensen: Færøsk madkultur, en oversigt. Søgu- & Samfelagsdeildin, 2003. (PDF)

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling