No more recycling blues

Many Norwegians help recycle by placing all their household plastic refuse in special blue plastic bags they get for free from their municipalities. In Romerike, a district on the outskirts of Oslo, smart new machines are making this individual effort obsolete.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

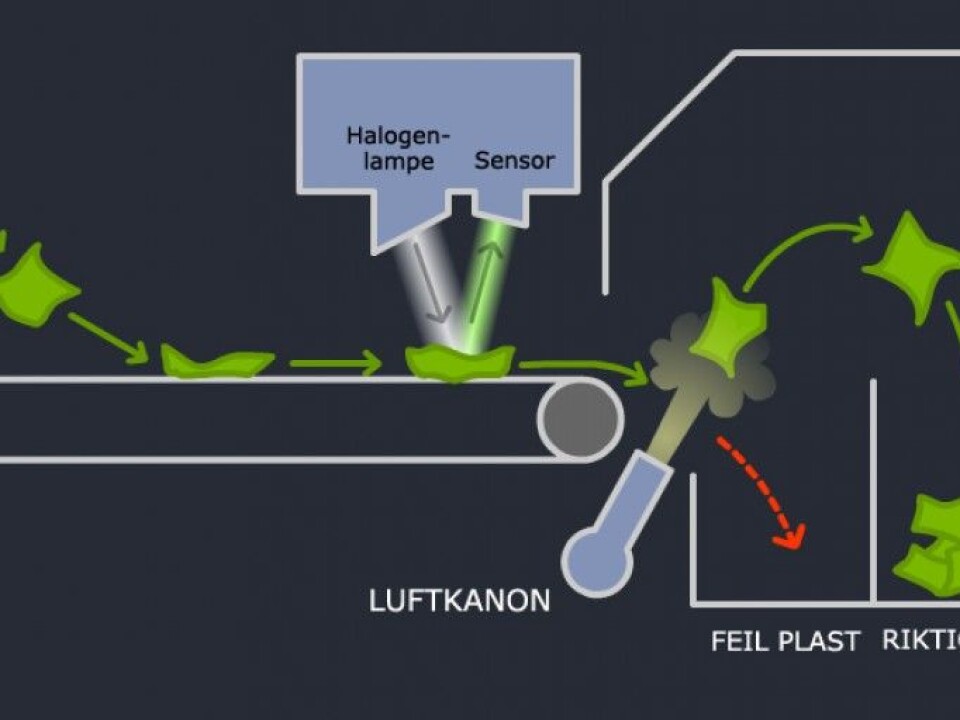

Endless loads of shredded bits of plastic race down a conveyor belt. The remnants of shopping bags, plastic wrap and other waste are lit up by a halogen lamp.

An angry popping sound erupts, like AK-47 bursts of air rather than bullets. Pieces of plastic fly up after being sniped by high-powered nozzles and are wafted into a bin. These are the selected bits of a particular category of plastic. The remaining pieces fall down into another container.

The conveyor belt races along at three meters per second. It looks like the plastic whirls up randomly but these are precision take-outs guided by high-speed electronics. Ten tonnes of rubbish are sorted into correct categories per hour. Only two percent ends up in the wrong bins.

Plastic in the same bags as general household trash

If you live in Oslo you are likely to have four different containers for rubbish under your kitchen sink. First you have paper, including milk and juice cartons. When you take out the trash these and your newspapers and other related products will go into the bin outside reserved for paper. While you are out there, you can toss the three other main categories of solid waste into the second rubbish bin you have out by the street. That one will take your food scraps, which you are supposed to accumulate in special green plastic bags distributed freely at grocery stores. Likewise, stores hand out rolls of blue bags to accommodate a household’s plastic waste. The fourth category is a sundry mix of general refuse.

So for simplicity’s sake, ignoring the batteries and empty glass bottles and other special items that must be delivered elsewhere, you have to sort your daily trash into 1) paper 2) food/organic waste 3) plastics and 4) miscellaneous solids.

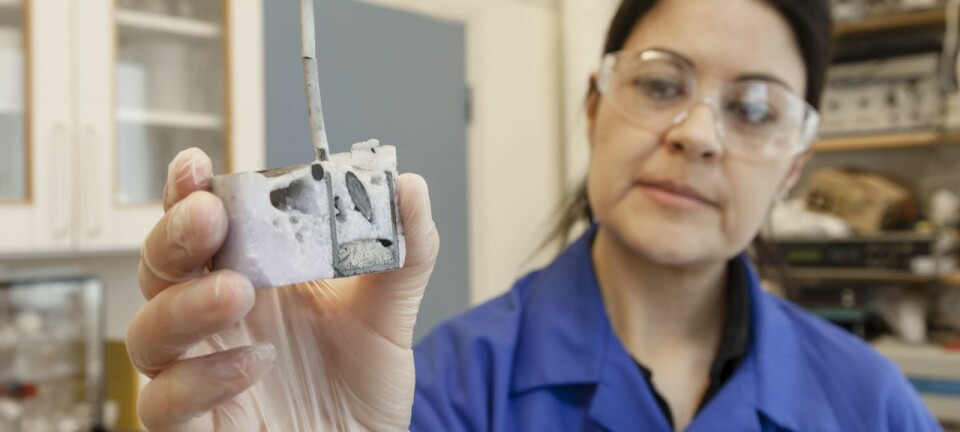

Needless to say, hardly anyone masters this waste management challenge in their kitchens 100 percent. This is why Romerike avfallsforedling’s (ROAF’s) new recycling plant northeast of Oslo has opted to turn one-quarter of the job over to computer-guided machines. These use optical recognition for different types of plastic on the basis of the colours they reflect under bright halogen lamps.

“Thanks to these machines, households can throw their plastics into the bags of miscellaneous refuse,” says Beate Langset, a director in charge of communications at ROAF.

The first step in the new process is for general refuse to be channelled into a tumbler which sorts out heavier materials. After that the lighter plastics are blown off, shredded and moved onward for further sorting.

Sorting plastics for recycling

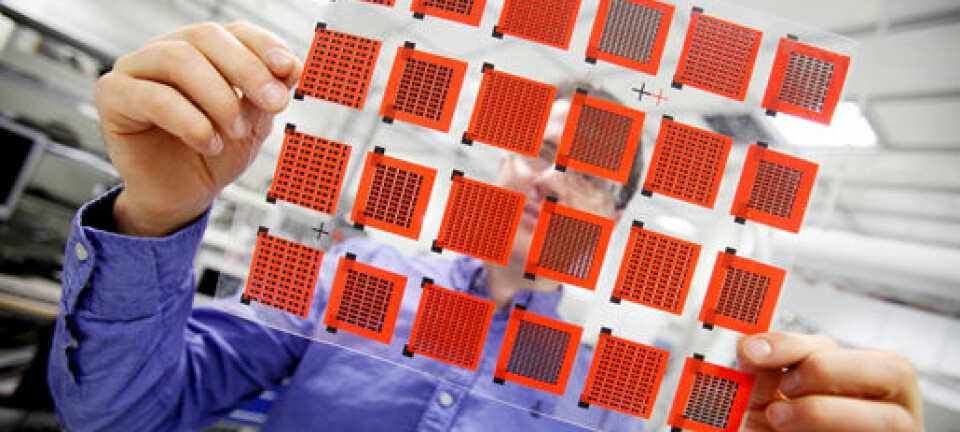

“The trash runs sequentially past 13 of these machines,” explains Ole Onsrud. He is the technical manager of the company TiTech, now a subsidiary of Tomra, a company that has made inroads with machines that sort deposit bottles and cans.

“Each of the machines blows off a separate type of plastic. The first one takes away bits of foil wrap and plastic bags. The next one blows off the PET, which is a type of plastic commonly used in soda bottles. Then there are polypropylenes and other types of plastic that can be recycled and used again,” he says.

Colour signature

The TiTech autosort machines make use of the fact that any given material has its own way of reflecting light. Some hues reflect a lot while others reflect little. In this context, materials have specific colour signatures.

“Black and very dark materials are a problem as they reflect so little light,” says Onsrud.

“We also have challenges with packaging where plastic is combined with other materials, for instance vacuum packs of coffee or crisps, nuts and snacks that use a metal foil,” adds Langset. “Those who buy plastic from us for recycling don’t want these materials.”

“Combinations of different types of plastic also pose problems, as do plastic-covered products like disposable diapers. We have to calibrate the machines so that they don’t sort these into bins for recycling,” she explains.

But Langset says plastic items smeared with organic substances like gravy and sauces are not a problem.

“Customers who take in dirty plastic have their own automated washers and are satisfied with the quality they get from our sorting facilities,” she says.

Green bags for organic garbage

Messy plastic from households is mainly smeared with dinner scrapings and the like, in other words, organic waste. Onsrud says that TiTech’s technology is also used to check foods at the other end of the chain, for instance the amounts of fats and water in minced meat. So why not use optical sorting systems for garbage so that Norwegians can also forget about those green bags for food scraps?

“This has never been under consideration. It would make the general refuse in our facilities much messier. When food scraps are sorted out by households into green plastic bags we are better able to ensure the quality of organic as well as mixed municipal solid waste,” says Langset.

“Also, we see that when they use green bags, the public becomes more conscious about how much food they actually throw away. So people end up wasting less food,” she says.

“Paper refuse can also be sorted with optic sensors,” says Onsrud. But for now this is only done industrially.”

This is why households must have special bins outdoors for their paper trash.

“The facilities can sort among cardboards, drink cartons and paper with various types of inks,” he says.

----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling