Little valley – a giant battery?

A new explanation has been given for the eerie floating orbs of light observed in Hessdalen in Norway. An Italian engineer thinks the valley could be acting as a colossal battery. But a Norwegian physicist is not exactly electrified by the clarity of this answer.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Hessdalen is an isolated rural valley about 45 minutes north of the picturesque Norwegian mountain town, Røros. People have been sighting UFOs – more precisely, orbs of light – in the sky here at least since the 1980s.

Italian engineer Jader Monari thinks the entire valley is essentially acting like a car battery.

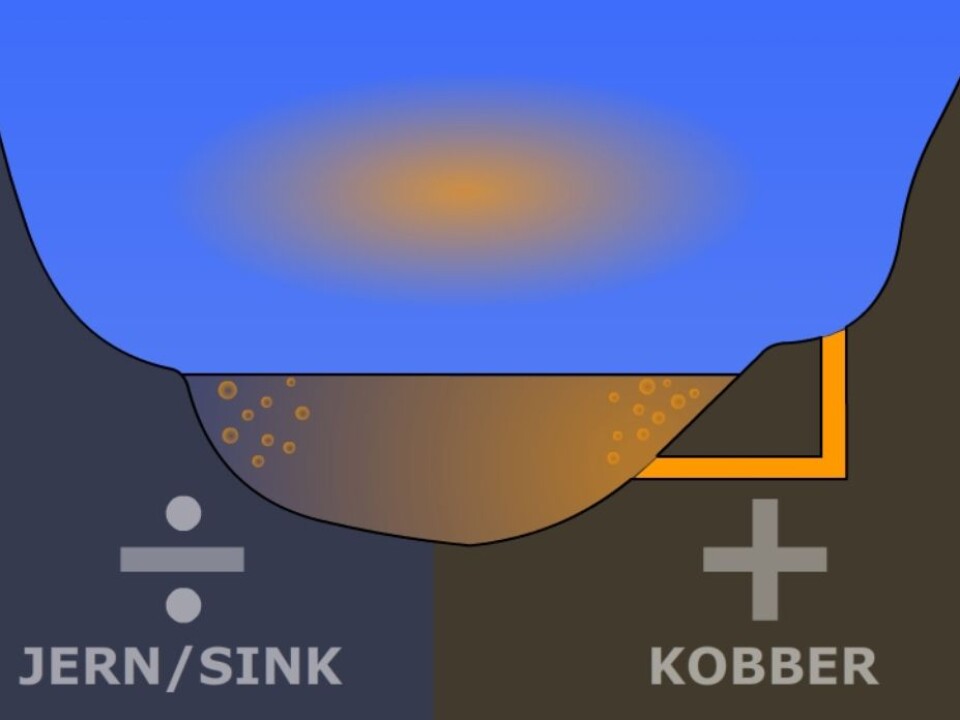

The battery that gets your engine started has two electrodes, submerged in a fluid that conducts electricity – an electrolyte. Monari thinks the two sides of the valley are the electrodes and the river Hesja can be acting as the electrolyte.

Gas bubbles up from the electrolyte when the current flows. These bubbles rise into the air and can become electrically charged by the geological battery. This can make the gas luminesce, proposes Monari.

In an article in the latest edition of New Scientist, he adds this theory to the many that have been proposed to explain the mysterious lights.

Existence documented

Monari is not the least in doubt about the existence of the Hessdalen lights. Engineers Bjørn Gitle Hauge and Erling Strand from Østfold University College have documented the phenomena since the early 1980s.

A technical report from their project’s web pages includes some blurry photos. The web pages also contain links to videos of orbs of light in motion.

“I haven’t seen any convincing computations of the phenomena at Hessdalen,” comments a Norwegian physicist, Bjørn Samset.

“Before launching more fantastic theories, I would start out with some thorough documentation,” he says.

Electric current in the river

Putting such misgivings on hold, what does the battery hypotheses claim?

Hessdalen is a valley running north to south. The western slope of the valley contains minerals partly composed of iron and zinc. The eastern side features rock containing copper.

In simple terms, the copper is hungrier for electrons than are iron or zinc. This can make the two slopes of the valley function like the anode and cathode of a battery.

Neither of the slopes could generate electricity on their own. This could only happen if the river contained compounds which could turn it into a conductor and thus cause chemical reactions like those in a battery.

Pure water is a very poor electrical conductor. But Hessdalen does have an abandoned mine that could be leaching sulphuric acid. That could turn the water into a conductor.

According to the article in New Scientist, Monari and his Italian colleague placed stones on either side of river. They found that enough electricity flowed from one to the other to power a light bulb.

Sulphur gas

The chemical reactions in a battery will sometimes also generate gas, for instance hydrogen from car batteries. Monari suggest that sulphur gas can be electrically charged when it bubbles up from the river and reacts with moisture in the air.

The electrical field between the sides of the valley can thus get a kind of grip on the charged cloud of gas and move it about, as the orbs of light have been seen to do by eye witnesses. Flashes of light are produced when the electric charges are released by the clouds of gas, asserts Monari.

Together with colleagues from Italy, France and Norway, he plans to buttress this hypothesis with new observations this summer.

Several objections

“I don’t think the phenomenon can be explained by such a battery. The distance is too great,” says Samset.

Another question is whether such an electrical field could provide enough energy to make the gasses glow.

“Electrically charged gasses, also called plasmas, normally have temperatures of thousands of degrees,” comments Samset.

The engineers who have been researching the Hessdalen lights admit that this poses a problem.

But they suggest that plasma can sometimes be formed at lower temperatures. Their observations indicate that the gas is cool.

“Cold plasma is a self-contradiction in my book, almost like hot ice,” comments Samset.

Dubious journals

He also says a quick examination of the journals referred to in the New Scientist article reinforce his scepticism.

“I can’t find the journal that supports the theory of cold plasma on the internet. Some journals mentioned do not have much of an impact factor and citations were lacking in references to other articles,” says Samset.

While entertaining serious doubts, he is not fully ruling out that the engineers behind the project in Hessdalen could be onto something.

“The problem is simply that they are proceeding too fast. There’s an air of desperation over the whole thing. I get depressed by research that is inadequately substantiated. In my opinion, New Scientist should never have published this article,” says Samset.

------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling