When bathing was medicine:

What can we learn from doctors who promoted sea bathing back in the day?

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Norwegian doctors believed that salt stimulated the nerves and that cold water could boost a person’s metabolism.

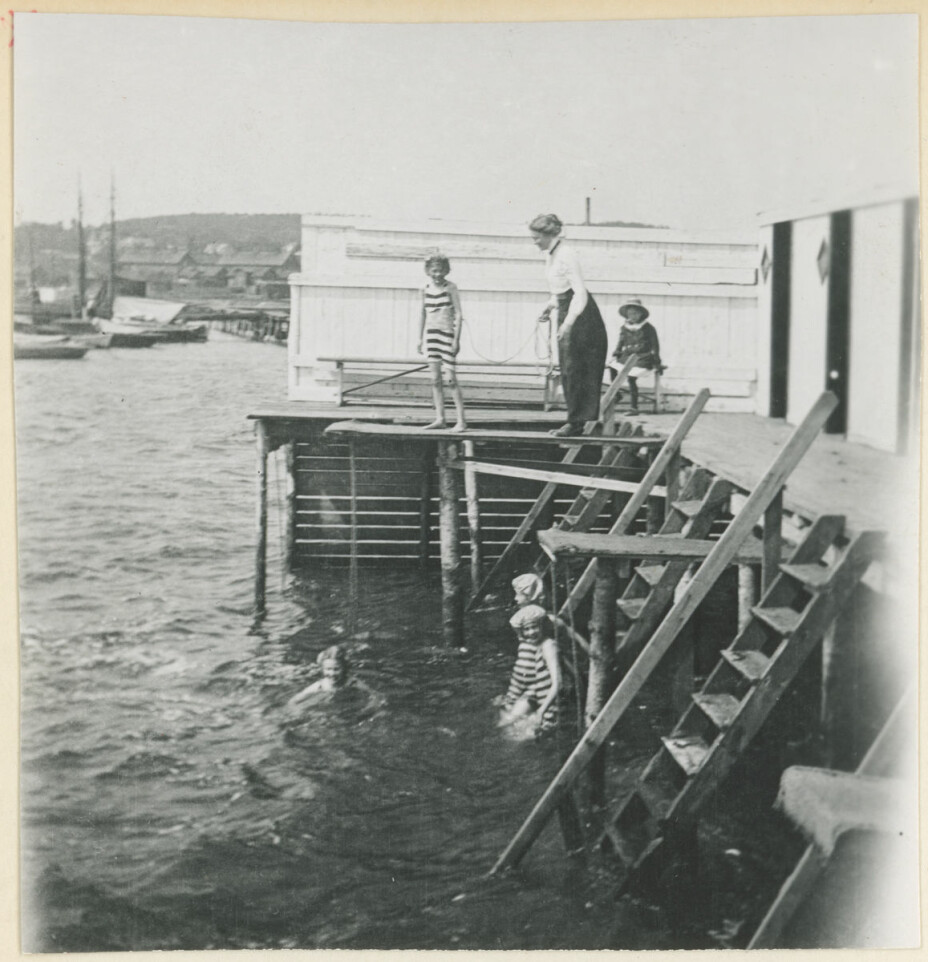

“A sea bath should be short — usually of a few minutes' duration; after the bath, a quick dry off, get dressed and then exercise,” wrote the doctor Peter Andreas Munch Mellbye in 1903.

The doctor also recommended that a patient not swim in the sea more than every other day when the treatment first began. Later, the person receiving treatment could increase to one bath daily. Two baths a day, on the other hand, were reserved for robust, well-nourished individuals.

Dr. Mellbye was one of many doctors in Norway in the late 1800s and early 1900s who saw sea bathing as a medical treatment.

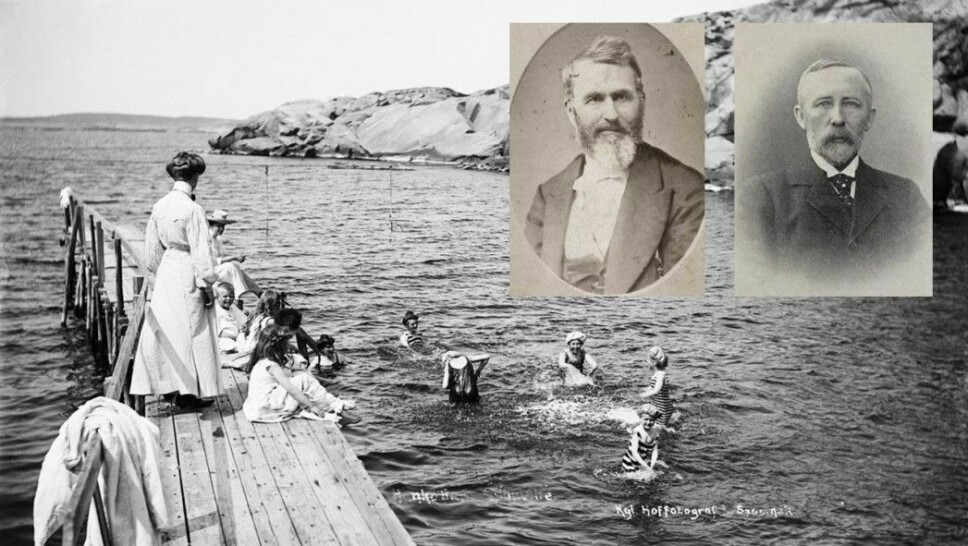

Several of these doctors worked at new spas along the coast of Norway, where sick people could stay for many weeks, according to Kristine Lillestøl, who has studied medical history at the University of Oslo.

Swimming in the sea was no joke for the doctors at that time.

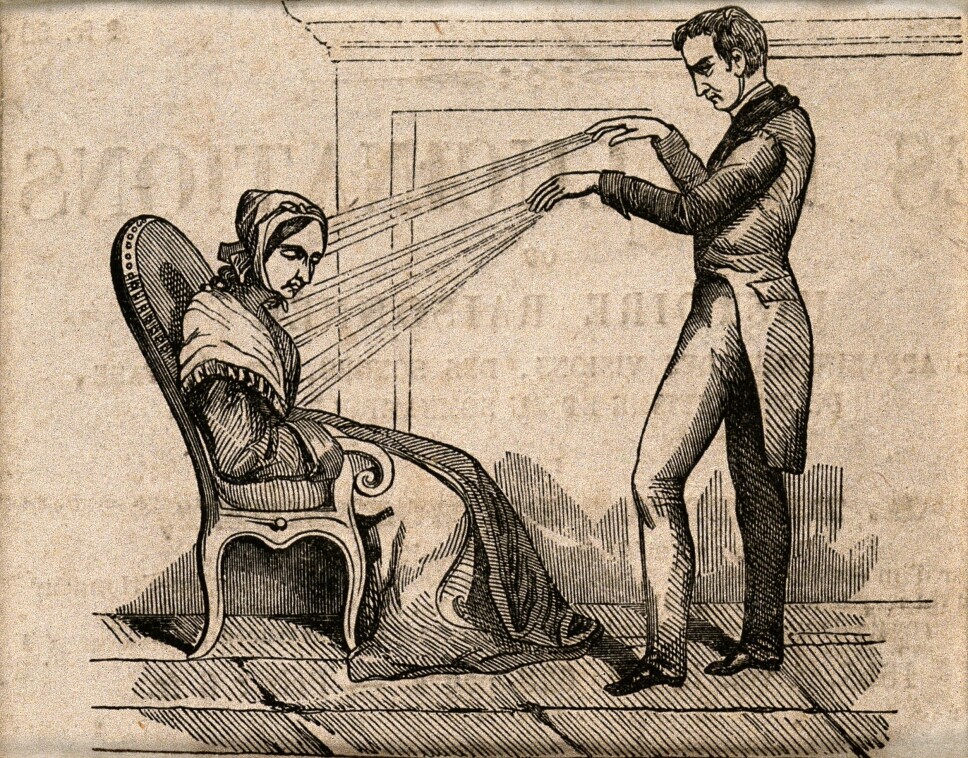

“Doctors assessed which patients should be prescribed a bath in the same way they decided who should be given medication. You couldn’t just plunge into the sea and think that everything would go well,” says Lillestøl.

But even though medical science has changed a lot since then, we may have something to learn from these "bathing doctors".

Hysteria and neurasthenia

Patients who came to the spas that sprouted up along the Norwegian coast in the 19th century had many different diagnoses.

Dr. Ingebrigt Christian Lund Holm listed some of the diseases that could be treated by swimming in the sea in a medical journal in 1886:

"Weaknesses due to previous acute illnesses, a torpid nervous system, mild anaemias not associated with weight loss, spiritual overexertion, hysteria, etc."

He also listed people with scrofulosis, which is now known as tuberculosis of the lymph nodes. And weak skin, rheumatism and a propensity to get a cold.

Lillestøl for her part has studied the old diagnosis of neurasthenia, which was a kind of state of exhaustion. Today, these patients would probably have received many different diagnoses, she says, including ME, anxiety and hormonal disorders, burnout or simply exhaustion.

Overstimulating salt content in the sea

Neurasthenia is a good example of a disease where doctors believed that only some patients would benefit from a dip in salt water. Although sea bathing was initially seen as a strengthening and stimulating treatment, an individual assessment was important.

“The patients who were more robust, well-nourished and only slightly overworked could take a bath, but that was not the case for people in really bad condition or who were malnourished,” the researcher says.

The cold water was thought to boost a person’s metabolism, which meant it should be avoided in some cases. And the doctors even thought that the salt in the water could be too intense for some patients.

“High salt levels combined with low temperatures could stimulate or irritate the nervous system more than what was thought to be good. The most exhausted and passive neurasthenics could benefit from a little stimulation, while for people who were initially very irritable, sleepless and restless, very salty, cold water could do more harm than good,” she said.

Detailed measurements and counts

It’s difficult to know how well the treatment at the spas actually worked, Lillestøl says.

There were many reports of patients who recovered from their stay at the spas. However, doctors lacked good ways to measure the effect of these treatments on their patients.

Nevertheless, they used the scientific tools they had at their disposal, Lillestøl said.

They measured everything from the mineral content in the seawater and in iron and sulphur sources to temperatures and air pressure. And everything was noted.

“They were very oriented towards making measurements and counts. But they still had a limited ability to investigate the effect on the human body,” says Lillestøl.

Jellyfish treatment in Sandefjord

Even if the spas actually made people better, it’s still not easy to know what exactly had an effect.

Treatment at one of Norway’s spas from the period was so much more than sea bathing.

“They also had massage and exercise regimens and more or less strict diet regimens. It was about living a strict, regular life. They didn’t really quite know what worked when people got better from being at the spa,” Lillestøl said.

Sandefjord Spa offered even more exotic treatments, everything from stroking jellyfish, swimming in fine-grained mud from the seabed and both drinking and swimming in sulphur-rich water.

These treatments were the brainchild of Doctor Heinrich Arnold Thaulow. He founded Sandefjord Spa in 1837 and is considered the pioneer in bathing medicine in Norway.

Many spas were opened in Norway in the late 1800s. Some of the most important spas that opened after Sandefjord Spa were the Larvik baths and Hankø baths, Lillestøl said.

Frightened and frozen poor people

But even though sea baths were a popular form of treatment, some doctors went to great lengths to warn people of the dangers of this cure.

"The sick and the afflicted have believed that the sea would hide their sickness and want, and the healthy have wished to exploit its strengthening ability to increase their capital of bodily health," Holm wrote, followed by a warning that the sea "always claims its victims, though not all who go there have found their grave."

He also had something to say to parents who let their children swim too much in the sea because they had heard that it was healthy:

"Some then find it their duty daily to bring their poor, small, frightened and frozen children, even in unfavourable weather conditions, out into the terrifying sea; under such conditions, of course, the organism is ill-suited to withstand the shock and heat loss, and it must be considered a success if the child escapes from this situation," he wrote.

Has inspired modern medicine

Lillestøl notes that several treatment principles from this period have found a place in modern medicine.

“We shouldn’t ridicule old spa medicine, because for all we know, these doctors may have been on to something. And there’s a lot of common sense in what they did. A spa stay usually lasted for several weeks, which meant you were away from work and lived a healthy life,” she said.

Today, a number of patient groups in Norway are offered treatments that are somewhat similar to the old-timey spa regimen.

Adults with the skin disease psoriasis and children and young people with atopic eczema can be offered treatment in warmer climes, says Teresa Løvold Berents. She is a dermatologist and researcher at the Regional Center for Asthma, Allergy and Hypersensitivity at Oslo University Hospital.

“They can be offered a three-week treatment trip with a strict plan that includes swimming and sunbathing,” says Berents.

In addition, a healthy diet, exercise, education and training are an important part of the stay.

Uncertain effect of sea bathing

There are several Norwegian studies that show that these treatment trips both help physically and give patients a better quality of life.

But do we know if actually bathing in the sea has any effect?

“No, we don’t really know,” says Berents.

Perhaps the salt water dissolves hard skin and dandruff. And perhaps salt on the skin improves the effect of sunbathing.

Sun and attention

Berents also won’t rule out the possibility that spa stays in the 1800s and early 1900s could help patients with many different diseases.

But instead of explaining the success of the treatment by swimming, she thinks the sun may have had a lot to do with it.

“The sun affects us in many ways. Among other things, it has been shown that it has an effect on many of the body’s physiological mechanisms. We haven’t done enough research on the sun's effect on the human body,” she said.

And much as is true for today's treatment journeys, it may well be that it wasn’t just one thing — but rather the whole experience — that made patients of the past healthier.

“A stay where you get a lot of attention can help your overall condition improve,” Berents said. “The psyche also affects the body.”

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

A. Lund, Kort fremstilling af de norske kursteders udvikling og kurmidler (in Norwegian, Brief presentation of the development and cure resources of Norwegian spas), 1880.

P.A.M. Mellbye: Norges kursteder og deres kurmidler (in Norwegian, Norwegian health resorts and their remedies), 1903.

I.C. Holm: Faren ved Anvendelse af kolde Søbad, navnlig hos Børn. (in Norwegian, The danger of using cold baths, especially in children). Norsk Magazin for Lægevidenskaben 1886.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no