General prosperity is a key to democracy

All of today's countries could become democratic regardless of their present form of government. Prosperity is a greater factor than religion in democratization.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

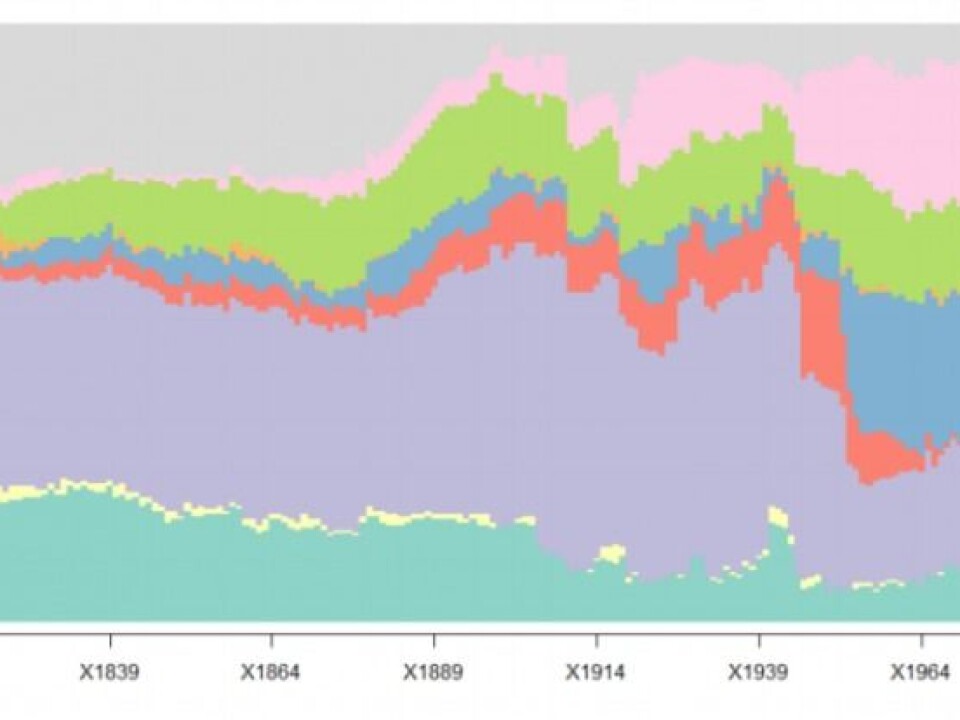

Swedish social scientists Mikael Sandberg and Max Rånge have analysed the political systems of every country in the world stretching back through history to 1789. The researchers at Halmstad University have found that democracy spreads from one country to the next – it doesn’t emerge within a country without external influence. This means that all varieties of non-democracies can become democracies.

Where it looked impossible

“Historic events and research in recent years show that democracy can emerge in contexts that previously weren’t considered possible,” says Carl Henrik Knutsen, a professor at the University of Oslo’s Department of Political Science. His comment refers to countries in Eastern and Central Europe, several in East and Southeast Asia and in particular in Sub-Saharan Africa. But not just there.

“Tunisia is a newer example which is often overshadowed by the military coup and lack of democracy in Egypt,” he adds.

Slower development

Research indicates that gross national product per capita explains much of why some countries become democratic and others not. But this explanation is less applicable with regard to Arab countries, where despite great wealth the development of democracy seems slower and unpredictable.

Sandberg and Rånge haven’t found an explanation for this, but instead say it requires more analysis.

Albrecht Hofheinz is an associate professor in Middle East studies at the University of Oslo. He thinks there is no automatic link between Islam and the absence of democracy, and that the reasons lie in political organizations rather than in religious ones.

“For years, many people in Muslim countries have expressed a desire to change their forms of government. The fact that they usually fail is not because of religion, but rather because of tangible domestic and global power constellations,” says Hofheinz.

Knutsen thinks it is hard to say what the reason is. But he too thinks that explanations other than religion should be considered.

“The same thing was said about Catholic countries a few years back, when they were non-democratic. But this changed suddenly when countries in Southern Europe and Latin America were democratized,” says Knutsen.

Modernisation on its way

Bjørn Olav Utvik is a University of Oslo professor and historian whose field of expertise is the Middle East.

He thinks it’s relatively easy to explain why there is not much of an apparent link between economic wealth and democratization in the Arab world.

“Generally, countries around the world that have high GNPs per capita are also ones that have undergone wide-scale and extensive industrialization and parallel modernization of most of their sectors. This has created an educated middle class and as time passed an organized working class which have won greater freedoms and initiated inclusive political systems,” says Utvik.

But the countries with the highest GNP per capita in the Arab world have not achieved this wealth through comprehensive modernization. These are countries which until a few decades ago were among the world’s least developed, but became rich because of the discovery of huge oil and gas resources.

“Indeed, this wealth financed rapid modernization. Now we see that a middle class is emerging and in keeping with textbook formulas it is starting to push for political rights,” says Utvik.

But these processes take time.

“The royal rulers in these countries have thus far successfully stunted demands for political rights by offering citizens a very rapid increase in living standards,” Utvik says.

Utvik added that most of the manual labour in many Arab countries is carried out by guest workers who have virtually no civil rights. So there is no substantial national working class that could demand change.

----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling