How are we affected by colours?

Does the colour of the room really affect our mood? And If so, is the effect universal?

Most of us have colour preferences, sometimes very strong ones. We reflect those preferences in the clothes we wear, the colours of furniture, floors and walls in our homes, and maybe even in the foods we like or cars we own.

Interior designers love to tell us that the colour of our surroundings plays a big role in our emotions, our productivity and our personality type. And often they refer to research as the basis for these claims.

But what does science say about how colours affect us? And do they have the same effect on all of us?

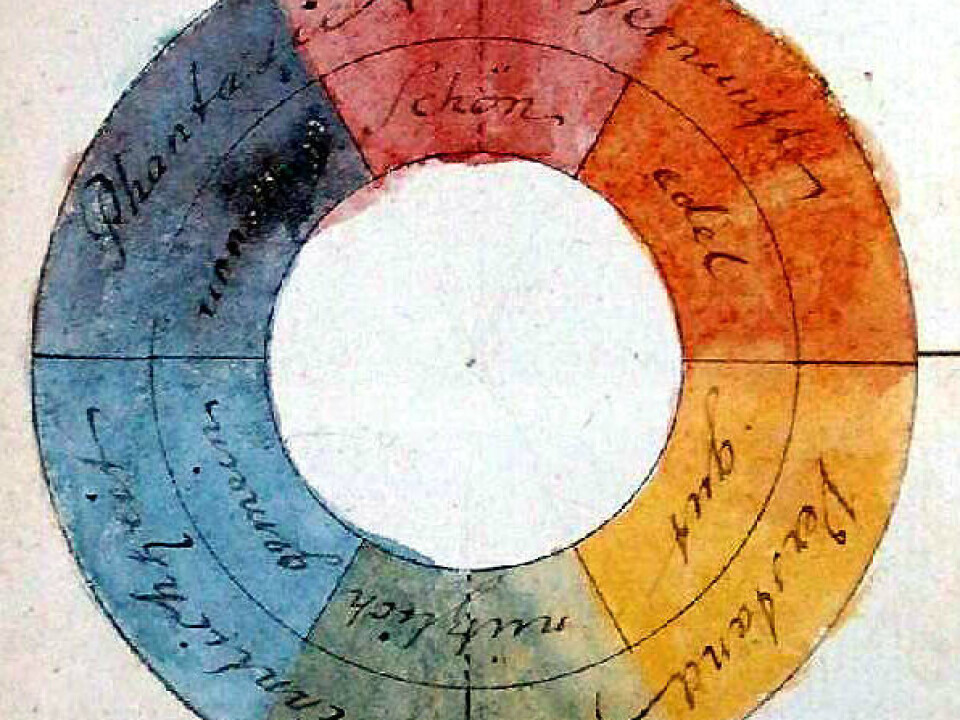

Goethe’s colour theory

In 1810, the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote a book about colours. The book was initially a response to Isaac Newton's demonstration of how white light is broken up into colours when it passes through a glass prism.

Goethe, by contrast, asserted that colours should be defined according to how we perceive them. He believed that colours symbolize different values.

For instance, yellow arouses joy, blue is a cool colour with melancholic tones, while green evokes indifference.

Although much of Goethe's theory is now disregarded, current research continues to plumb the question of how colours affect us.

“Associating green with nature and yellow with pleasure is probably not scientifically based,” Klemens Knöferle tells forskning.no.

Knöferle is assistant professor at the BI Norwegian Business School and an expert on how various sensations, including colours, affect us as consumers. He believes that it is important to distinguish between what marketers do and what scientists actually do.

Even if you think about nature when you see green, it doesn’t necessarily mean that your reaction is innate. You may well have developed the association through different life experiences.

Knöferle believes that the idea that blue is a boy colour and pink is a girl colour, for example, is reminiscent of popular theories inspired by Goethe's colour theory from the 1800s.

Not all research is equal

Many studies exist that examine how we react to colours. But Knöferle is sceptical of many of them.

“The method is often a problem in these studies,” says Knöferle. “If you take older studies and check them for other factors, the proven effect often disappears.”

He says we forget that there are many different aspects of colour, for example how light or dark a colour is or how strong or weak it is.

In an email to forskning.no, Zena O'Connor, an Australian colour psychologist, points out that researchers often decided in advance that certain colour relationships existed and set out to prove these alleged links. These studies rarely used more than six to twelve colour swatches or more than ten subjects.

“In addition,” she says, “researchers then often transferred these small discoveries to much larger contexts, or an entire population.

Knöferle has been involved in conducting an experiment in which participants were asked to taste white wine in rooms of different colour. Subjects who drank wine in a red room found it tasted sweeter than when they were in a white room. Those who drank wine in a green room found it tasted more acidic.

Other international studies also suggest that white and gray walls are often seen as boring and not very creative, and that a little colour in the office helps improve employee mood.

NASA interior

In 1988, even NASA jumped on board to research whether colours can have a universal, almost innate power. Why? Well, to figure out the optimal colour for the interior of a spacecraft.

Researchers concluded then that it is unlikely that we have an inborn reaction to colours, either physically or psychologically.

Rather, they think rather that the associations we develop with colours can trigger a physical reaction.

Is blue a modern invention?

Not only NASA thinks that our reactions to colour are mostly individually and culturally determined. Some scientists believe that culture determines what colours we are able to distinguish from one another at all.

A Radiolab podcast tells of the 19th century scientist and politician William Gladstone, who conducted a study of colour references in antique literature. The most famous example is the description of the sea as wine-red in the Odyssey. But the word blue doesn’t exist anywhere in Homer's classic epic.

It turned out later that several ancient texts from different cultures had no references to blue.

The idea that people of that era might not have been able to see blue sounds pretty farfetched. Just look at the sky!

But a study conducted among the Himba people of Namibia shows that it isn’t quite so simple. Subjects were shown a picture with several identical green squares and one blue square. Most failed to point out the blue square.

When, on the other hand, the subjects saw the same image, only this time with one square a slightly different shade of green, they could all point out the square that was different. For some of us that’s impossible (try it for yourself here).

Why? The researchers believe it’s related to our culture. The Himba have no word for blue, but they have numerous words for green. They obviously see the colour, but probably don’t notice it, suggest the scientists.

Complicated picture

O'Connor believes it is important to keep in mind that several individual factors influence our perceptions of colour. She believes that very few colours have a universal effect.

“The relationship between reactions and colours is so complicated and it can be affected by everything from age and gender to memory and culture,” she says.

In addition, she points out that the way we react varies widely from person to person.

How about red?

Knöferle mentions only one colour that possibly has the same effect on all of us: red. But how can we know if it's true?

“First, we have to determine whether the colour has a cultural impact and demonstrate it, for example among Norwegians. Then we see if we can find the same effect in a distinctly different culture,” says Knöferle.

forskning.no previously wrote about how the colour chartreuse arouses disgust among Britons, while it evokes delight among the Himba people. The two groups also had quite different associations with the colours, which were influenced by the environment around them.

So it’s unlikely that chartreuse has a universal effect on humans. But what if both cultures had reacted similarly? Could we say that the effect is same for all people?

To determine that, says Knöferle, “we should also test whether the colour has an effect on animals similar to us - like chimpanzees. If they have similar reactions to the colour, and the results can be repeated in several independent experiments, then we can say that there is something universal in the colour’s effect.”

He adds, “Red is known to have an arousing effect among some animal species. In some cases their testosterone level increases when they are exposed to red.”

Red can also be linked to human arousal, writes psychologist Noam Sphancer in Psychology Today. He cites blushing cheeks as an example.

Or maybe not...

Nor is the research showing this link in short supply. Some studies suggest that women in red arouse interest among men. Sphancer thinks this is subconscious. He points out that most of the men who participated in the studies were not aware of the purpose behind the experiment: to demonstrate a correlation between red and attraction.

But other findings dispute this relationship, according to psychologist Susan Krauss Whitbourne in an article on the same site as Sphancer.

For example, another study has shown that babies prefer red over green, regardless of their gender. If men were pre-programmed to prefer the colour red, one would think that more male children would prefer the red.

She speculates whether our ability to detect colours that are important for survival is what’s universal, but that which colours we actually prefer and what we associate them with are culturally determined.

------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Scientific links

External links

- Klemens Knöferle's profile

- 19th-century insight into the psychology of colour and emotion - The Atlantic (2012)

- Hear more about William Gladstone and the colour blue in this podcast from radiolab.org.

- Hear more about Goethe's colour theory in this lecture series on YouTube by Pehr Sallström.