When ice becomes as thick as this, it could linger for months

The roads and sidewalks in Norway are covered with an extremely thick layer of ice. Why does this layer form, and what does it take for it to melt?

The perfect recipe for the thick layers of ice that coat many Norwegian roads and sidewalks is lots of snow that melts and refreezes.

On 15 February, the Norwegian Meteorological Institute issued a warning about slippery roads in large parts of Southern Norway. The reason: There were reports of lots of precipitation, which could come in the form of snow, sleet, and freezing rain.

The precipitation will probably also result in more ice.

Why do thick layers of ice form?

“It becomes particularly treacherous if it's been cold and snowing a lot, and then rain falls on top of it," climate researcher Hans Olav Hygen at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute tells sciencenorway.no.

What does it take for thick layers of ice to form? State meteorologist John Smits says it’s the result of two factors:

- There has been a lot of snow.

- The ground is cold.

This combination faciliates the formation of thick ice when warmer air temperatures first arrive.

“If the weather is mild for a couple of days, the snow melts a lot. If the ground has been very cold before, the water quickly freezes again,” the meteorologist says.

He compares the cold ground to the freezing elements under an ice rink.

Could last until April

So when will this thick layer of ice disappear this year?

The answer depends on how many days with temperatures above freezing Norway gets moving forward, Smits tells sciencenorway.no.

He himself

lives in Eastern Norway and finds it difficult to predict how long the ice

will remain there, but he points out that it can take time to get rid of the thickest

ice.

“It can often be very persistent. If you've got a thick base of snow that has been soaked and frozen, it can quickly become 10 centimetres thick. We might be dealing with thick ice like this well into March and April," he says.

More thick ice in the future

This is something Norwegians just have to get used to it. People in various parts of the country should expect more ice and slush in the coming years.

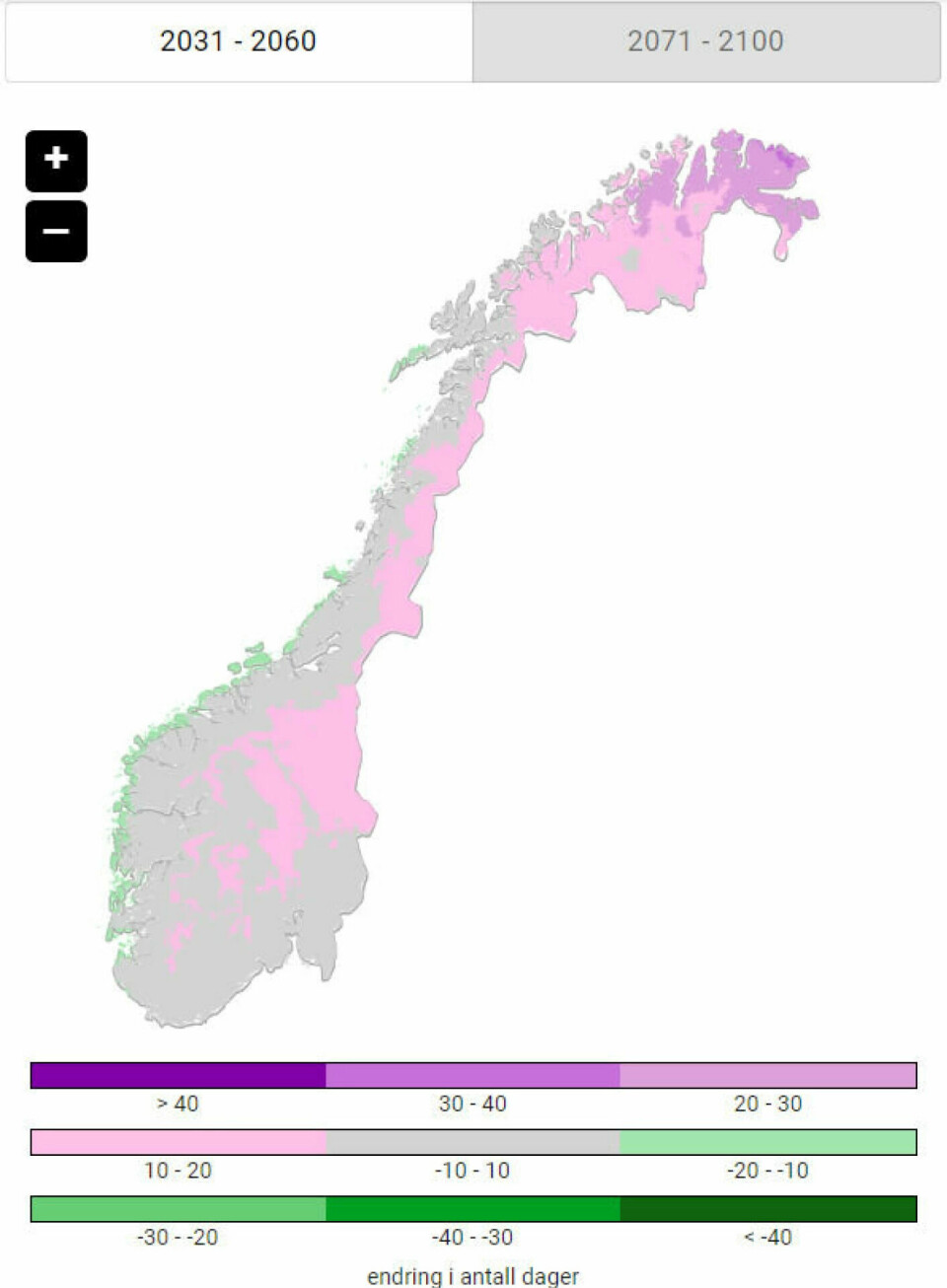

These were the findings from a 2020 study from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, which was published in International Journal of Climatology.

Temperatures will fluctuate much more frequently between above and below freezing in future winters, especially in the far north of Norway and inland regions.

“Large parts of Norway that have normally had cold winters will have winters where temperatures are closer to zero,” Hygen says.

However, even though climate scientists estimate that Norway will experience more days where temperatures hover around zero degrees in the future, 2024 has not been a record winter so far in this respect.

In contrast, the winter has been relatively stable compared to last year, state meteorologist Smits reports.

Less thick ice along Norway’s west coast in the future

For those living along Norway’s west coast, it’s worth noting that not everyone will experience more thick ice due to climate change.

On the contrary, a warmer climate will lead to fewer fluctuations between above and below freezing temperatures in some coastal areas.

The explanation for this is that these areas already have warmer temperatures for much of the winter, Hygen says.

Ice, slush, and treacherous conditions

But regardless of how cold Norway’s future may or may not be, there may be some consolation for residents in the fact that the country has gone through many winters with treacherous conditions in the past.

On 20 January 1930, the Gjøvik newspaper Velgeren wrote that the winter weather at Biristrand was the strangest people could remember in many years.

"Icy and slippery driving conditions have alternated with slush and treacherous conditions andall other kinds of messy conditions," reads the description.

In the winter of 1991, the Tromsø newspaper Nordlys was full of complaints about icy conditions.

"The bus stop below the school is covered with a thick layer of ice where people are more likely to fall than stand. It's a wonder that no one has slid under a bus," a pupil told the newspaper on 8 February 1991.

And last winter, Dagsavisen reported traction sand shortages, and mirror-slick schoolyards in Oslo (link in Norwegian).

Reference:

Nilsen et al. Projected changes in days with zero-crossings for Norway, International Journal of Climatology, vol. 41, 2020. DOI: 10.1002/joc.6913

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no