Why does physical activity exacerbate symptoms in ME/CFS and long Covid patients?

“It can resemble overtraining in athletes,” says Professor Nina Vøllestad.

Researchers can argue about a lot. But in one area, researchers worldwide have been remarkably unanimous:

Physical activity is healthy for both body and mind.

Even though intense training can hurt in the moment, the activity has a positive impact on everything from the heart and lungs to cognitive abilities and mood.

Similar positive effects are linked to activity on other levels, such as social activities or various forms of mental training.

But for ME/CFS sufferers, and some patients with other illnesses like long Covid and fibromyalgia, this is often not the case.

Instead, fairly mundane activities can send them to bed for days, with symptoms like extreme fatigue, flu-like feelings, pain, brain fog, and – paradoxically – sleep problems.

This is called PEM – post-exertional malaise.

You can read more about how PEM behaves in this article: Victoria Augustine Trulsen falls ill from everyday activities like taking a shower or family visits.

Physical, social, mental, and emotional stress can cause these abnormal reactions, and it doesn’t matter if the cause is an enjoyable activity like reading a novel or visiting friends.

But what is PEM?

No blood test

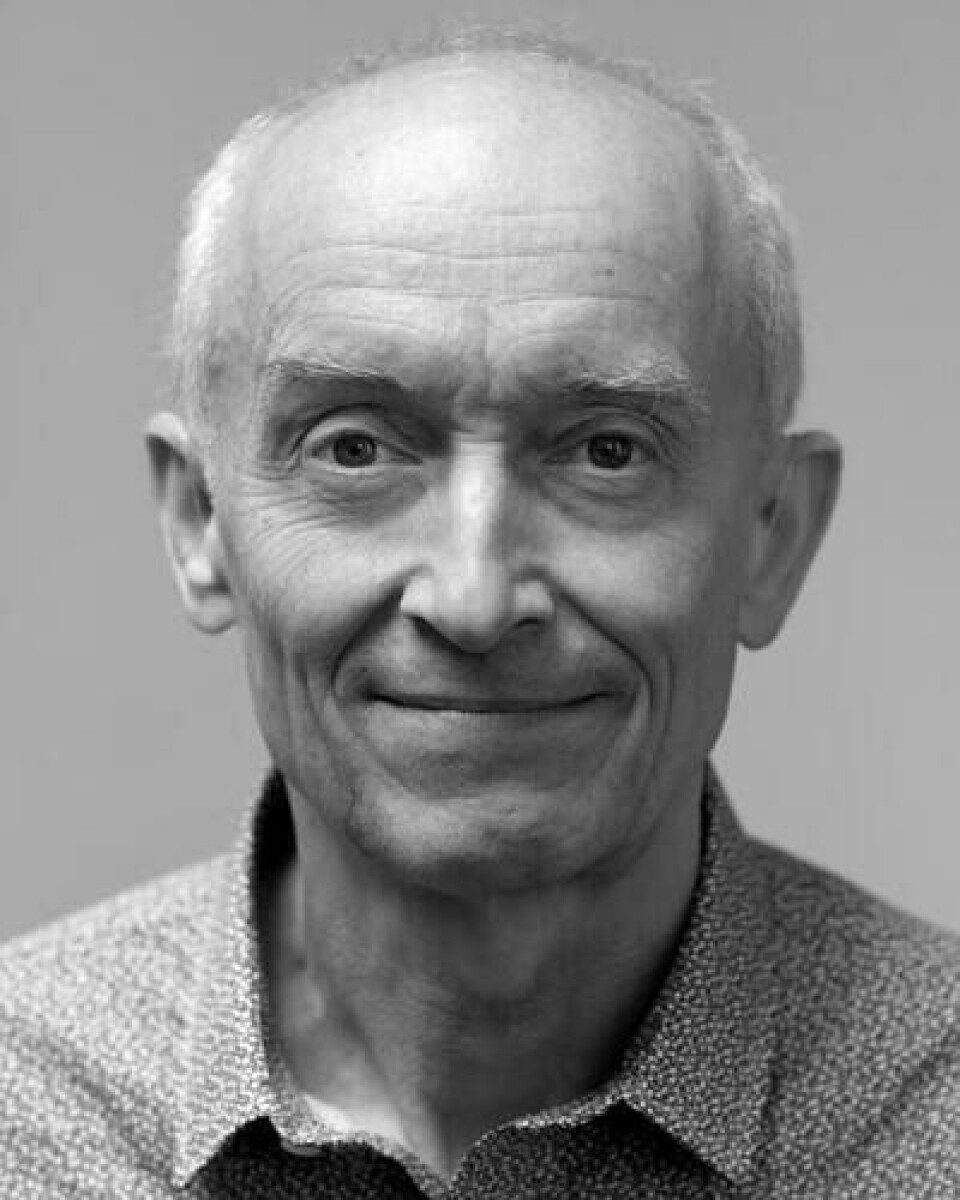

“PEM is a striking symptom that is completely reproducible,” says Kristian Sommerfelt.

He is a paediatrician and senior physician at Østfold Hospital Trust Kalnes, professor emeritus at the University of Bergen, and has worked with children and adolescents with ME for many years.

Doctors or researchers can provoke PEM in patients, for example, by subjecting them to an exercise session or a demanding mental task.

But what actually happens is far more uncertain. Doctors currently have no simple blood test or measurement that detects PEM.

Much of what we know about PEM comes from patients' descriptions of their own symptoms, says Sommerfelt.

But there are also studies that confirm these descriptions.

Testing exercise capacity

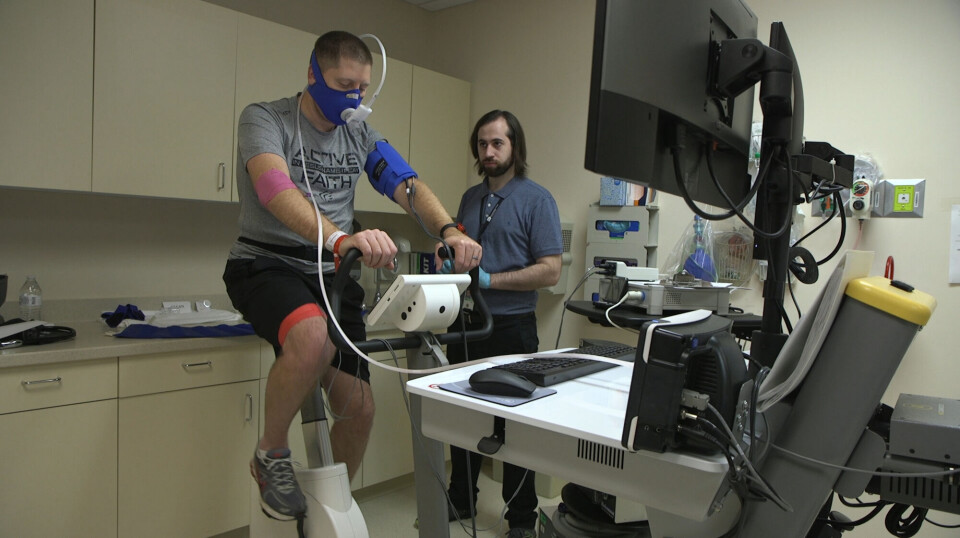

A type of test called repeated CPET measurements can precisely show how a session of physical activity affects a person’s condition afterwards.

A CPET test – also called a VO2 max test – is a very precise measurement of exercise capacity, or how fit you are. The test involves taking a series of physical measurements while the test subject performs a workout, for example, on an ergometer bike.

Researchers then get a picture of what happens in the body while the person is exercising.

But the really interesting thing about PEM is having the patients repeat the same test twice.

Researchers have let people with and without PEM take a CPET test. And then, a few days later, the individuals repeat the same test. This can show whether the first training session had an impact on the subsequent one.

Characteristic differences

Such studies, including a Norwegian study from 2019, have shown characteristic differences between ME/CFS patients and healthy individuals.

A summary from 2022 concludes that ME/CFS patients are in significantly worse condition on the second test. They perform worse and the lactic acid in their muscles builds up faster. This does not happen with healthy people.

It also does not happen with people who have other serious chronic diseases such as heart failure, COPD, and cystic fibrosis, according to a 2024 National Geographic article.

The results from repeated CPET tests can confirm the patients' descriptions of their symptoms, Professor Nina Vøllestad and Professor Emerita Anne Marit Mengshoel write in a recently published summary of the research on PEM.

They believe the research suggests that ME/CFS patients may have changes in energy metabolism in their muscles and the response of the autonomic nervous system. This is the part of the nervous system that controls heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and digestion.

Changes in multiple systems

There have also been other types of studies linking PEM to physical changes in the body.

A study from 2017 showed, for example, that strenuous mental tasks led to changes in the brains of ME/CFS patients that were not found in healthy people. The changes could correspond with the patients' experiences of having an impaired ability to think and concentrate after the activity.

Several studies have shown abnormal reactions to physical activity, such as poorer pain regulation and changes in the immune system and its interaction with intestinal flora, according to a summary from 2023.

A study was also recently published in which researchers examined the ability of muscles in long Covid patients with PEM to produce energy.

Problems in the cells' powerhouses

Rob Wüst from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and his colleagues had taken muscle samples from healthy individuals and those with long Covid, both before and after a controlled 15-minute exercise session.

It turned out that long Covid patients stood out even before the test. Their muscles had a greater proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibres. And after exercise, even more differences emerged. There were signs of severe muscle damage and lower activity in the mitochondria, which are the cells' powerhouses.

The researchers also observed that long Covid patients had muscles that were less able to absorb oxygen from the blood than healthy individuals.

Most viewed

The study had relatively few participants, and more research is needed before it can be confirmed that these changes are characteristic in those with PEM. But the results also suggested interesting areas that could be investigated further.

“If the mitochondria in muscles are dysfunctional, this means the muscle cells don't produce enough energy to meet the body's demands. This may explain why people with long Covid experience worse symptoms after exercise,” Caroline Dalton from Sheffield Hallam University wrote in a popular science presentation of the study on The Conversation website.

Out of shape?

An interesting question is whether the experiences of ME/CFS patients and long Covid patients could be due to deconditioning – that is, being in poor shape because they have been inactive for a long time.

According to a study from 2022, there is reason to believe that poor fitness contributes to some of the symptoms ME/CFS patients experience during the exercise session. Here, the researchers compared ME/CFS patients with similarly inactive individuals.

But the study also showed that the ME/CFS patients differed from other chronically ill individuals, such as in having issues in oxygen metabolism.

All in all, there is little evidence to suggest that poor fitness is the explanation for PEM – the characteristic worsening of symptoms following exertion – which in many cases does not involve physical activity at all.

Not a result of poor fitness

“Physical inactivity itself does not cause PEM,” Wüst and his colleagues wrote about the patients they examined in their study.

“PEM is a unique symptom in these diseases and is not the result of deconditioning,” David Systrom from Harvard Medical School said to the American radio channel National Public Radio (NPR).

In a summary from 2023, Systrom and his colleagues write that poor fitness does not lead to the physical changes that they see in the bodies of ME/CFS and long Covid patients with PEM.

Neither do the researchers that sciencenorway.no has spoken with believe that PEM can be explained by poor fitness.

“This probably has nothing to do with deconditioning. It appears to be something the patients react to neuroendocrinologically, which makes the body respond differently after physical activity,” says Vøllestad.

Sommerfelt suggests that the illness' progression often indicates that PEM is not related to poor fitness due to long-term inactivity.

“PEM occurs at the onset of the illness. Most people can remember which week they fell ill, and PEM is a characteristic already from the first weeks and months,” he says.

May be different disease patterns

Studies on the illness show that something abnormal seems to happen in the bodies of those who experience PEM. But there is still a lot that is not known.

For example, researchers have mostly examined PEM triggered by physical exercise so far, because it is easy to set up tests and measurements. But ME/CFS patients say that PEM can just as easily crop up after social or mental exertion, or from physical activity that is much less strenuous than exercise.

Researchers do not know if this is due to the same mechanisms as exercise-induced PEM.

They also do not know if the same causes underlie fatigue and symptoms in the muscles and general fatigue throughout the system. A 2016 study suggested that these might be different phenomena.

“It's possible that we're talking about completely different clinical pictures,” Vøllestad says.

She also believes that existing research may provide a distorted picture, because the patients in the studies had to be able to complete a physical training session.

This probably means that the participants who were selected either had a lighter disease burden or were in a recovery phase, according to Vøllestad and Mengshoel.

Vøllestad believes we need much more research.

“We don’t primarily need studies of the effect of individual measures, but investigations to gain a more fundamental understanding of what PEM is,” she says.

Vøllestad believes an interesting place to start would be to study what happens in the recovery phase – that is, in the period during which the body rebuilds itself after a workout.

Resembles overtraining

“When we engage in demanding activity, we get tired and need to recover,” Vøllestad says.

After a long hike in the mountains, we need to rest before our body is back to its baseline and ready for another hike.

“But if recovery is slower, as it seems to be with ME, and you continue as usual, then your problems accumulate. There's a mismatch between how you use and recover resources,” she says.

Vøllestad paradoxically sees interesting similarities between PEM in ME/CFS patients and the symptoms of athletes with overtraining syndrome. Overtraining is where the athlete does not get enough recovery time between training sessions over a long period.

“They're not back to baseline before they start again. So, they wear themselves out, and it can take half a year to recover. The symptoms are very similar to ME/CFS,” says Vøllestad.

The question is: Why don’t ME/CFS patients recover normally?

But here, there are few answers.

“We lack research on biological changes during the recovery phase,” she says.

——

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no