What exactly is Down syndrome?

Marte wishes people knew more

Marte Meisingset loves to sing and hang out with friends, but gets upset if someone teases her.

When sciencenorway.no speaks with Marte Meisingset on video, she has just returned home from judo practice. She is wearing a white outfit with a green belt.

“I once had white, and then I had yellow. Then it was orange, and now it's green,” says the 16-year-old from her family's living room.

Marte has Down syndrome and is in 10th grade at Tangenåsen secondary school. She enjoys it there.

But there are some things she wishes more people understood about what it's like to have Down syndrome.

An extra chromosome

Every year, some children in Norway are born with Down syndrome. In 2022, 42 children with the syndrome were born. When you are born with it, you have it for the rest of your life.

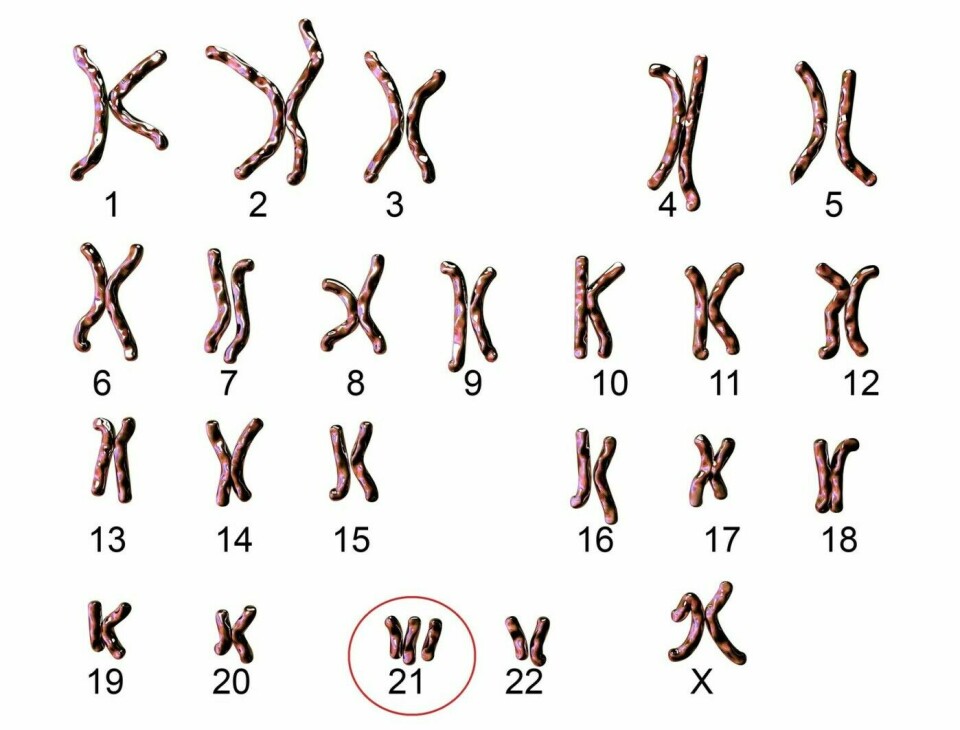

People with Down syndrome have an extra chromosome in their cells.

Children are usually born with 23 pairs of chromosomes. In each pair, there is one from the mother and one from the father.

Inside the chromosomes is our DNA. DNA is the recipe for everything from how the heart works to what colour hair you have.

But sometimes the child gets three of chromosome number 21. Usually, the third comes from the mother, according to Norwegian Health Informatics.

Then the child has Down syndrome.

Needs more help

No two children with this syndrome are the same, but it is common for the body to develop a bit slower than usual.

It can also be difficult to learn things that other children find easy. Like speaking and writing.

Some are also born with heart defects, difficulties with seeing and hearing, or weaker muscles.

So what was it that Marte wished more people understood? Well, namely that she needs more time to learn new things. That she needs more help with homework and more help if she gets stuck.

Many find secondary school difficult

Sometimes other children have teased Marte for being different.

“You get a little upset if someone bullies or jokes,” says the 16-year-old.

Fortunately, she has friends who support her when she is not feeling so good.

Not everyone has it like that.

Followed children with Down syndrome until they became adults

Secondary school can indeed be a difficult time for many with Down syndrome, says Kjersti Wessel Jevne.

Together with several other researchers, Jevne has taken part in a research project.

The researchers have interviewed children with Down syndrome from the age of five. They have also interviewed their parents.

Today, the children are young adults in their mid-twenties.

Achievement is possible for all

The school has a responsibility to accommodate all children, says Jevne, underscoring the importance of not underestimating those with Down syndrome.

Not everyone can achieve everything, but everyone has the opportunity to achieve things, she points out.

"Help and support are absolutely necessary for teenagers with Down syndrome too. But they must be allowed to have a say in what kind of help and support they need," says the researcher.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no