Enhancing individual treatment for rectal cancer

Intestinal cancer is a common form of the disease in Nordic countries but is hard to treat. Norwegian researchers are trying to tailor treatment better to the individual patient.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

We thrive on oxygen and our cells need constant supplies of it, so you might think that cancer cells get increasingly active the more they get.

On the contrary, some of the cancer cells in a tumour which get little oxygen can become aggressive and all the more harmful.

“There are blood vessels inside the tumour that carry nutrients around, but some areas have less access than others.”

“This starts up biological defence mechanisms in the oxygen-deficient cells which make them spread more rapidly, and the tumours grow increasingly faster,” says Kathrine Røe Redalen, post doctor and physicist at Akershus University Hospital (Ahus).

One problem is that medical technicians treating a cancer patient are unable to see which parts of the tumour are starved for oxygen, a tissue condition called hypoxia. Perhaps researchers can do something about that.

Røe Redalen leads a project which uses, among other things, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer modelling to analyse tumours and attempt to reveal which parts get oxygen or not. Her research is part of the OxyTarget study, which is investigating several aspects of rectal cancer, including biomarkers in blood samples.

Rectal cancer

Rectal cancer is one of the commonest forms of cancer in Norway, and the disease can be hard to treat.

About 1,400 women and 1,300 men among the country’s five million citizens were diagnosed with large intestine and rectal cancer in 2013, according to the Cancer Registry of Norway. Røe Redalen says about a third die within five years.

“Patients with rectal cancer usually need a stoma operation because the tumour and the tissue around it must be surgically removed.”

Røe Redalen hopes to see new methods of treatment put to clinical use for these cancer patients.

“Nearly everyone with tumours in the intestinal wall undergoes surgery, but it might not always be necessary. There are differences among malignant tumours and we think treatment can be optimised individually better than today.”

If the patient has a small tumour it will usually be immediately surgically removed. If the tumour is larger it needs to be treated with chemo-radiotherapy to be shrunk before surgeons can remove it.

“The areas of the tumour which are oxygen deficient react less to radiotherapy, but there are drugs that increase the effect of the treatment. The problem is that we don’t know who to give these medications to,” explains Røe Redalen.

If doctors could learn more about their tumours some patients might be treatable with less drastic procedures than a colostomy or ileostomy.

How to look inside a tumour?

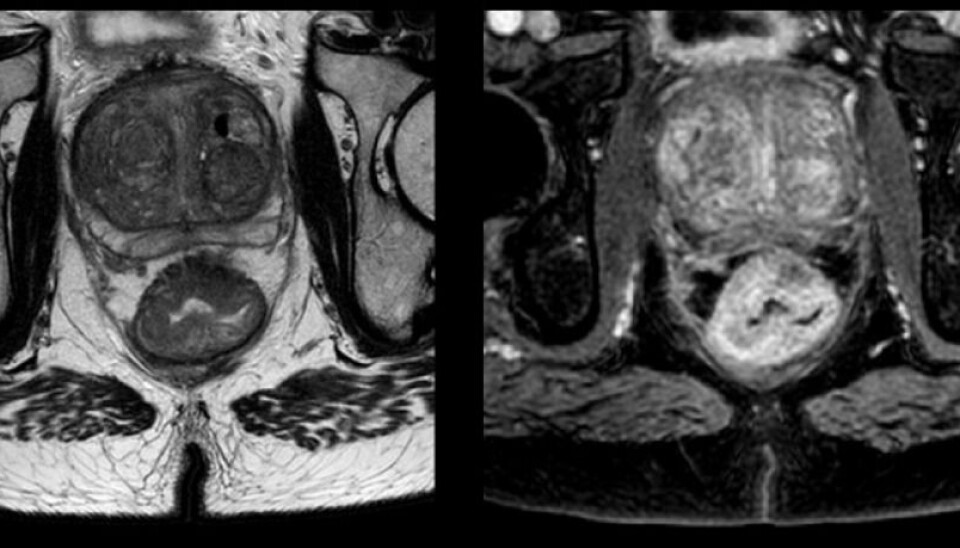

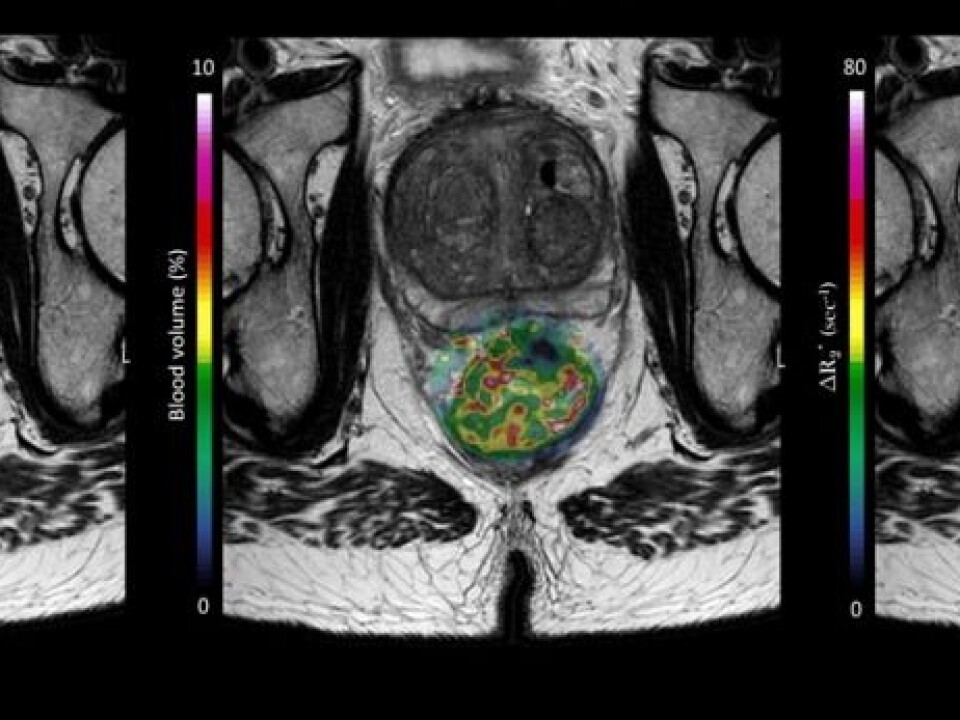

The researchers in the study use MRI to see the tumour inside the body, as in the picture below. This patient has a large rectal tumour.

The patients are given a contrast medium while lying in the MRI machine. This is a solution that shows up in the images, enabling the medical scientists to follow the flow of blood into the tumour. A picture of the tumour is taken once a second for five minutes.

Software displays how the contrast medium moves through the tumour and the results are used in a computer model that locates the hypoxic areas. The data model also provides information about the tumour’s metabolism and the flow of blood inside it.

“We hope to use the results together with blood samples, feed these into a computer and, for instance, get answers on the risks of spreading for individual rectal cancer patients.”

This would help doctors in choosing a treatment regimen that is designed for the patient’s type of cancer, particularly how aggressive it is.

That is still something for the future. The researchers also need to recruit more patients to the study. Kathrine Røe Redalen thinks the project can be finished toward the end of next year.

Computer model

“This is a computer model, not a measurement of reality. All patients are different, so we don’t know yet whether the modelling can be made sufficiently accurate.

“We probably won’t get the answer to that until five years after the patients were treated. We won’t know whether the predictions have been correct until then.”

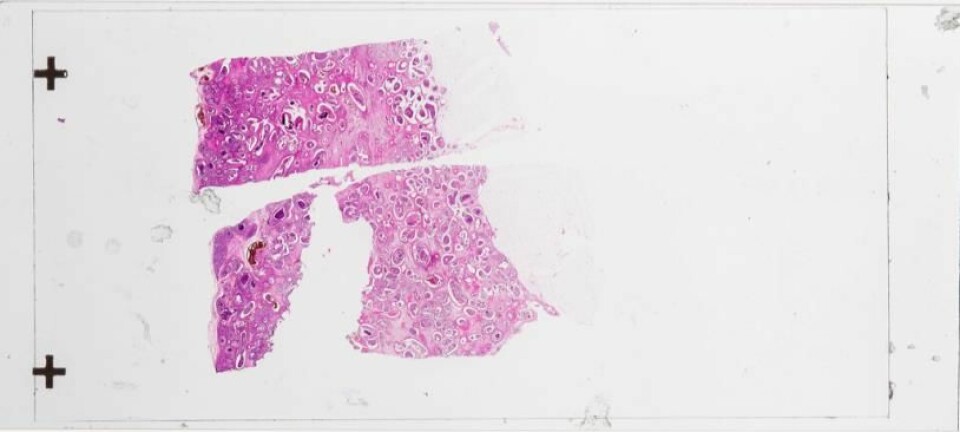

In another part of the study, tumours are examined after being surgically removed. The researchers can then compare them with the MRI pictures. They can also try to determine which genes and proteins could reveal information about how aggressive the tumour was.

Excited

“I think this study can turn up some very interesting discoveries,” says Siver Andreas Moestue. He is an associate professor and cancer researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and has worked on the study at Ahus.

“They are making some smart choices when they combine the various MRI techniques to analyse hypoxic malignant tumours,” he comments about the OxyTarget study.

Mostue explains that information about such oxygen-deprived tumours can be very useful for doctors when trying to optimise dosages of radiotherapy for their patients.

Doctors seeking to spot hypoxia in tumours now need to take biopsies or monitor oxygen uptake in the tumour with using electrodes.

“It would be really great if we could examine the tumour without a surgery,” says Moestue.

“I am optimistic enough to believe that in the future we will find drugs that are especially effective against the hypoxic parts of a tumour.”

It could be that these oxygen deficient parts of the tumour have a key role in the development of the disease.

“A tumour is not a homogenous group of cells. Many think now that the outcome of the disease is impacted by the aggressive, hypoxic clumps. As a matter of fact, our group has seen a link between hypoxia and the risk of metastasis in experimental animal models,” says Moestue.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling